Kama Sutra

A Spiritual Fable of Eunuchs and Orgasms

A Spiritual Fable of Eunuchs and Orgasms

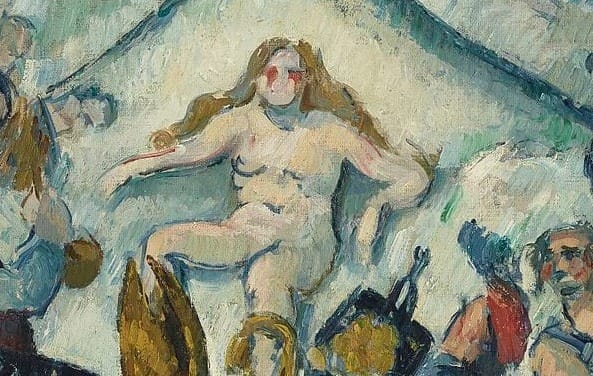

Once upon a time, you bit into the apple and things were never the same again. Was there ever a better way to experience the divine? Neither music nor art nor literature could ever compete with sex, although we have tried hard to turn it into fruit metaphors.

Yet why choose the apple? It is not even mentioned in the Bible and it was always less appealing than the peach or the pomegranate or the banana. There is something cold and unyielding about an apple... Compare it with those flower metaphors: the rose, the lotus, the orchid, the lily, where sex was folded into the shape of the petals as well as in the scent.

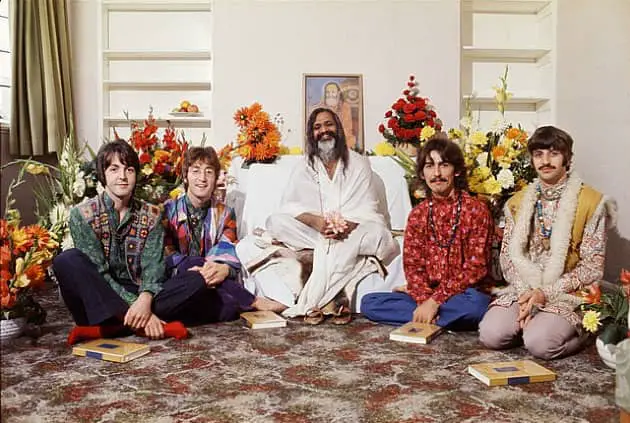

The Beatles at Rishikesh

There is a story that is now passing into legend about how the Beatles, Donovan, Mike Love of the Beach Boys, Mia Farrow and her sister (Dear) Prudence all went to Rishikesh, India in February of 1968. Perhaps they went to learn meditation from Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Perhaps they went to relax and write songs away from the media? Perhaps they went to spend time with their wives and girlfriends? Or perhaps, as others would have it, they went to have great sex and drugs. John and Ringo were 27, Paul and George were 25 (Mia Farrow was 23).

Jealous Guy

According to the legend, the Beatles, or at least John and George, fled the ashram because they believed rumors that the Maharishi had hit on a young woman, who may or may not have been Mia Farrow (Paul and Ringo had already left.) Details are disputed to this day but supposedly John became upset because the Maharishi claimed to be celibate and here he was chasing after the women. John’s outrage is not so surprising given that he was still a Liverpool lad at heart. While he was never faithful to Cynthia, and in Rishikesh he appears to have thought about no one else but Yoko Ono, apparently there was something hypocritical about the guru himself having sex when John wasn’t having it with Yoko. Added to that was the Beatles’ resentment that the Maharishi had been using their relationship to build his own financial empire.

Now it very well may be that the young woman was not Mia Farrow at all, and it very well may be that the rumors were started by Magic Alex, John’s jealous ex-guru (a Western one at that), and it very may well be that it was really John who hit on Mia Farrow. Who really cares? But celibacy was an issue here because many gurus did claim to be celibate, like the Buddha, like Gandhi. Brahmacharya.

Sexy Sadie

For many Indians though, it was really about the drugs. Take Deepak Chopra, who studied with the Maharishi and who knew the Beatles. During a guest editor stint with The Times of India in early 2006, Chopra wrote:

The Beatles — along with their entourage, which included Mia Farrow — were doing drugs, taking LSD, at Maharishi’s ashram, and he lost his temper with them. He asked them to leave, and they did in a huff. But when they went to the US, John Lennon gave an interview on the Johnny Carson show, accusing Maharishi of being a dirty old man. Later, Lennon also wrote a satirical song about Maharishi, which went: “Sexy Sadie, what have you done/you made a fool of everyone.” But I’m sure there was never any truth to Lennon’s allegations.

Chopra’s comments largely passed unnoticed in the Western media but the reaction from many Indians in India and the West was striking: the Beatles were just the latest in a long line of hypocritical Western tourists to come to India for drugs and sex under the guise of spiritual enlightenment. Furthermore, by writing the Sexy Sadie satire, John Lennon retaliated in a truly mean-spirited and even racist way. Most Indians were just as cynical about the intentions of the Maharishi, of course, especially as they watched his TM empire expand across Europe and the United States, but that didn’t make it right.

Glass Onion

Nowadays, the Rishikesh story is one of those glass onions where you can make the pieces take different shapes according to what you want to believe – a sexual fable. Maya... In the years since, George and Paul contradicted John’s claims. They exonerated the Maharishi, who comes across as genuinely celibate but politically reactionary. Along with Cynthia Lennon, they also argued that they were incredibly productive in composing songs because they were not taking drugs. None of the biographies support Chopra’s contention.

Then why did John say it? In 1980 he said, in a Playboy interview: “Listen, if somebody’s gonna impress me, whether it be a Maharishi or a Yoko Ono, there comes a point when the emperor has no clothes. There comes a point when I will see.” This seems to be what it was all about, not the sex or drugs. John had come to see the Maharishi as just another opportunist and he was bored and impatient to move on. As Joseph Campbell once remarked (sarcastically): “(Gurus) know that they have the path, and they know where you are on the path.” Such arrogance also ticked off John, who never had much time for Mother or Father figures. Like Campbell, John loved the fact that in life, as in romance, there is no path, no book of rules, at least in the West there isn’t.

John turned now to Yoko Ono as his new guru, so that he didn’t have to walk alone, but transcripts of his subsequent encounters with gurus like A. C. Bhaktivedanta read like hilarious absurdist plays. Eric Idle could do no better. It is not appreciated enough that John and Yoko always viewed these gurus ironically and competitively through those glasses of theirs. By thinking in this way John began to transcend his Western identity in a way that the other Beatles never did, even George, who embraced Hare Krishna. That said, transcending your given identity can also produce a terrible spiritual loneliness, especially when you are using heroin.

Instant Karma

It has been said by others that after Rishikesh, the Beatles grew up and that’s what drove them apart. John changed from a rock icon with a wicked sense of humor into a kind of guru himself, the only Beatle to do so, a Siddhartha to George’s Govinda. This is ironic, given his rejection of gurus. The shift is noticeable in his move from whimsy into the more serious political songs and in his use of “you” – directly addressing his audiences in a way the other Beatles rarely did (“I Want You,” “Instant karma’s gonna get you”). It has always made John something of a Chinese puzzle himself. Go into any bookstore and there’s a row of books on John and barely anything on the others. It could be said, “That’s because John is Dead, not Paul.” I don’t agree with this, although I do think the best history of the Beatles is Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now by Barry Miles.

Not every guru wants the responsibility of having followers. Followers are like groupies, or apsaras, and for a private person like John, that quickly became alienating. Krishnamurti is the most famous example of a guru rejecting being a guru (the Maharishi and A. C. Bhaktivedanta, on the other hand, loved it). John continued to reject being a guru, most notably in the song “God,” and over the years he morphed into something else again. “Saint” may come closest, but not in the sense ridiculed by Miles in his McCartney biography. John had his flaws, but he came to seem like a Buddhist saint, a Bodhisattva, because it was his spirituality that people responded to. You could not take your eyes off him and he seemed to be tapped into some universal inner karma. India did make its mark on the man.

This is to take nothing away from Paul and the other Beatles. But it is interesting to look back at Swinging Sixties Liverpool and London, when Siddhartha’s river first began flowing strongly in both directions. Indian immigrants poured into Britain while another river – of hippies – flowed back to India. In going to Rishikesh, John was like those others, wrestling with the Kama Sutra, discovering that sex was a magical and transformative feminine energy coiled within himself, a Kundalini, a serpent waiting to rise. Later he would call himself Kaptain Kundalini.

God

For all that, John was heavily influenced by his Anglican upbringing all his life and it trumped India’s or Japan’s charms. With Rishikesh receding into the past, there was his famous drugged-out moment when he declared to the other Beatles that he was Jesus Christ, “a revelation that they accepted with equanimity” to quote the ironic Miles. John continued to make Christ-like allusions (“they’re going to crucify me”) throughout his life, and the U.S. government nearly succeeded in doing it.

John’s appeal – like Bono’s – was as a seeker and a truth-teller like Christ, in the sense that he stripped away everything and talked about it publicly and poetically. Unlike Bono, he found nothing much there. Music, alcohol and drugs and even Yoko never filled the gap and by the mid-Seventies he was tempted by born-again Christianity (like Dylan). He must have known he was missing something but he couldn’t figure out what it was and he was always too cynical and in-the-present-moment to stick with anything. Unlike the other Beatles, he showed his pain in the 1970s and yet he seemed somehow to catch occasional moments of transcendence, moments of genuine fun, unassisted by religion, and that is why millions of empathetic fans around the world felt it too. John Lennon held a glass onion up in front of all of us in which many were willing to see themselves. When it shattered in 1980, he was only 40 and, for better or worse, the whole sorry tragedy came to resemble the martyrdom of Christ. He would have hated it.

Guru Dutt and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam

In 1962, around the same time the Beatles landed their first recording contract, Ingmar Bergman won the Academy Award for best foreign language film. His masterpiece Through a Glass Darkly is named for the famous line from 1 Corinthians 13. But there was an Indian film that same year that just as eloquently uses the same metaphor. It won multiple awards in India but had little or no impact in Berlin or on the Academy in Los Angeles.

In Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, a wife sits at home every night, in despair because her husband is out with dancing girls and courtesans and drinking himself into a stupor. What makes a man leave his wife for other women? What can she do to make him happy? It is a question pondered over by the storyteller, played by Guru Dutt, who hears her poignant singing in the still night air.

Like Yoko Ono, she makes a fateful decision. If the only thing that will keep him home is to start drinking with him, then that is what she must do. And she does, with disastrous consequences. For an Indian wife should be purity itself, the pillar that holds up the house and instead it literally comes down around her. Yoko eventually kicked John out, but by the end of Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, the wife is dead and her impotent fool of a husband is dead. What else could she have done? Certainly she discovered that he was impotent, which was not a good sign. Without sex we die quicker.

Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam is sometimes translated as King, Queen Knave or (more literally) King, Queen, Servant. It was shot in Mumbai but it is set in Kolkata at the end of the 19th century during the era of the British Raj. It evokes a nostalgia for a time long gone, of palatial mansions and wives who do not leave their homes. Aside from some odd blemishes, it is a masterpiece on the scale of Citizen Kane in the way it functions as a meditation on time and memory, sexual desire and death. There is a real sense of the divine that breaks through the black and white images and the melancholy music. This does not occur to everyone watching it, no doubt, but it does appeal to enough Guru Dutt fans (among which can be counted many Indian film writers) for it to be true enough to say so.

Whatever Gets You Thru the Night

Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam is also a masterpiece that bleeds into real life… In the film, if two out of four lead characters end up dead, in real life two out the four actors were soon dead from alcoholism, along with Guru Dutt’s wife (Geeta Dutt, a famous playback singer, whose voice is heard in the film). Like John Lennon they were all dead at the ages of 39 or 40 or 41.

Guru Dutt was the first to go at the age of 39, in 1964, only two years after Sahib. There is still much debate about whether it was an accident or suicide, but when you are alone and vast quantities of alcohol and sleeping pills are involved, sometimes a dividing line isn’t that important. It was his third attempt and it appears he was still upset that the relationship with Waheeda Rehman (his love interest in real life and in the film) was over and he could not be reconciled with his wife, Geeta. So there is a sense in which he projects his desperation into the role of the desolate wife in Sahib, drinking her way to oblivion. He blew his mind out in a car/He didn’t notice that the lights had changed… Manidvipa.

Meena Kumari, who was already a major star when she played the wife in Sahib at the age of 30, was dead at 39. Like her character, her marriage was disintegrating at the time (she would be separated two years later in 1964), and she began to drink herself to death in the company of younger men. Her poetry (in Urdu) resembles the wrenching songs that Geeta Dutt sang for her. Geeta Dutt herself had been devastated by her husband’s death and she slid through a nervous breakdown before returning to the drink. Like Kumari, she died from cirrhosis of the liver. The two women died the same month, in July 1972. Naraka.

In My Life

How did it get to this where, luminous and alive, they drank and drugged themselves to death? Why did their private lives come to so closely resemble their screen lives? It does mean, of course, that the land of the Kama Sutra is really an illusion of maya conjured up by daydreamers and that Indians suffer from the same things as everybody else, especially in Bollywood. But it also means that alcohol and drugs don’t get you to Heaven, and they may not even improve sex with your wife or husband. Rather, the wheels go round and round and then they come off.

Sir Richard Burton, The Kama Sutra and The Arabian Nights

Sir Richard Burton began his own slow fade through the glass darkly in Trieste from 1871. When he married Isabel in 1861, he was 40, and it was an energetic match; they traveled together for 10 years. They never had children, much to Isabel’s regret. It is hard to know what he felt about it. So was the translator (or, really, the polisher) of the infamous Kama Sutra of 1883 sterile, or was his wife? We don’t know.

"My earliest influence of living in different points of time at the same time was in the house I grew up in. It had 17 clocks and 11 mirrors. All the clocks gave different times." - H. Masud Taj

Sitting on the sea wall at Miramare in Trieste, Richard Burton is churning the ocean and dreaming of Lakshmi above the waves. He was now 50, in semi-retirement, sidelined from his diplomatic career. The inveterate traveler wrapped himself in his writing in this cosmopolitan seaside town for almost two decades, working on the cycle of books that would make him an enduring figure of mystery for literary historians, puzzled by his sexual appetites and determined to nail him as a pederast, a closeted homosexual, an epic hero, a guru, a truth-teller. Biography is the genre of character assassination.

I am the Walrus

The Kama Sutra only became a catalog of gymnastic sexual positions in the Western imagination in the Sixties when translations first began to appear commercially. But long before Burton encountered it, it was an Indian marriage manual. No ordinary one. More than a handbook for correct sexual behavior, it includes such fascinating things as “The Wives of Other People” (and we all know what that’s about), and The Third Sex (which Burton translates as “eunuchs” and which has a large folklore too large to go into here). Put another way, who else but a married man would bother to catalog all those sexual rules and regulations instead of just getting on and enjoying it? The original writer, Vatsyayana, was said to have been celibate, from which we can assume he was No Longer Married.

Yet, at the core of the manual, and the reason Burton became so obsessed with it, why it came to consume all his writing, is something else: it is the question, “Is this it? Is this all there is to life?” This question usually strikes men and women after the age of 40 as sex becomes less frequent. Or harder to do. Or less exciting than it used to be. The onset of a phased withdrawal… Menopause... Burton finally settled into this third phase of life – dharma – by the time he was 50.

There is a wonderful story in Burton’s The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night. Beginning on the 644th Night, Scheherazade tells the Emperor, Shahryar, of a magic spyglass that Prince Ali buys which is able to show anyone whatever their heart desires, even if it is many hundreds of miles away. Now, Prince Ali turns out to be the middle son of the Sultan of India and he travels all the way to Shiraz in Persia to find this magic spyglass and in the end he is the one lucky enough to get the girl they all desire, the Princess Nur al-Nihar. (His older brother Husayn finds the famous flying carpet while the younger brother Ahmad, finds a magical apple that will cure any illness – see, apples are good for something.) The Emperor, Shahryar is so fascinated by this woman telling him stories every night that he quite forgets to have sex with her. But given how many women he has executed already, it does seem that the Emperor was averse to sex, a woman-hater. A eunuch perhaps.

Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds

The spyglass (like the carpet and the apple) serves as a metaphor for Burton’s imperial surveys of India, Africa, the Islamic world, Asia, the Americas. Drawing on his encyclopedic knowledge of exotic sexual practices, Burton scandalized the Victorians and even some critics today. In Volume 10 of the Supplemental Nights, Burton surveys Pederasty across "The Sotadic Zone" and it makes for interesting reading, with references to evil and racial slurs that discover pederasty in all its many forms in every corner of the globe. Burton was writing at a time when the entire world seemed awash in cannibalism, bestiality, incest and polygamy, let alone heathen religious beliefs, which is why imperialism was sorely needed in the first place. If the British public delighted in such rationalization, nevertheless it was risky for Burton to publish such material (the Obscene Publications Act of 1857) and so he sold these books via private subscriptions rather than at retail and occasionally he lashed out at his critics:

Why does not this inconsistent puritan purge the Old Testament of its allusions to human ordure and the pudenda; to carnal copulation and impudent whoredom, to adultery and fornication, to onanism, sodomy and bestiality? But this he will not do, the whited sepulchre!

He is right, of course, but the hilarious and ironic conclusion for the reader coming to the end of this splendid effort is Where is London in this churning ocean of pederasty? Even Paris and Berlin are covered! There may be a satirical intention at work here, of course, but it leads some critics to assume Burton was himself a pederast. This does not strike me as accurate, even allowing for the “methinks the lady doth protest too much” argument. Rather, Burton strikes me as a romantic who genuinely does disapprove of pederasty.

In his own life, Burton comes across not as a eunuch like the Emperor Shahryar but as a storyteller like Scheherazade. They both want to stay alive another night. Burton had read the scientific studies that linked longevity to infertility, the implication being that he would probably live longer if he did not have sex with Isabel. After all, fertility and having children were unnecessary distractions that occupied the lower classes but the rich could do without them, couldn’t they? Not that he was that rich. Equally, it seemed likely that good health (for men at least) was related to an active sex life, because flushing the blood through the body orgasmically surely would prevent future erection problems and heart disease. What to believe? At least it would also help keep Britain white and prosperous. Today, many Western couples have embraced Aldous Huxley’s solution of a Viagra pill (they're a new, shiny blue apple) or vibrators shaped like tropical fruit or vegetables (they're better than the red apple).

Nowhere Man

Burton celebrated sexuality and spirituality in everything he wrote, almost as if they were one and the same. This was not a popular view, shared neither by the rebels against Victorian era morality, from Oscar Wilde to the Bloomsburys, for whom art was more important, nor the upper classes for whom Christian sex should be for procreation, at least officially. Many contemporaries resigned themselves to the inevitable and simply gave up sex. In other words, early on in life, many in Europe’s chattering classes became eunuchs, which may be defined as the refusal to procreate. When Nietzsche looked around for a metaphor to mock them with, he chose the eunuch:

Our contemporary men of letters, men of the people, officials, and politicians (are)… a race of eunuchs; for a eunuch one woman is like another, in effect, one woman...the eternally unapproachable...

Of course, Nietzsche himself was celibate for decades (admittedly not by choice), so sex was on his mind too.

If the chattering classes lost interest in sex (the working classes didn’t), there were many looking around for some spiritual alternatives in the early 20th century. A few proclaimed the superiority of the Greeks, the Kabala, the I Ching, or the Occult, but Shaktic and Tantric thought were the most popular and they continue to be to this day. Filtered through Rosicrucianism and Theosophy, its exponents almost eliminated sex by arguing that orgasms were no longer necessary. Even to this day they maintain that sex is wonderful, I’m sure, but prolonging the build-up should be the real goal, so that experiencing orgasmic feelings becomes a constant, not just a temporary release of sexual energy. Why waste vital fluids?

Kundalini, they decided, would be all about getting that female sexual energy out of the “lower” parts and elevated up the spine to the masculine heart and brain, where thinking people knew it rightfully belonged. Shiva in his thousand-petal lotus and all that… It all sounds like an excellent “upper” class idea. In a wonderful gesture of selflessness, many almost eliminated orgasms altogether from their daily lives, from Alice Bunker Stockham, Havelock Ellis and Arthur Avalon, to Joseph Campbell and the Maharishi, eunuchs all. Even Rajneesh (Osho), who talked about sex constantly, was said to have been celibate between the ages of 42 and 55. Freud, who knew nothing about India, is said to have informed his wife that he had decided to become celibate at the age of 40 for similar reasons.

Hermann Hesse and Siddhartha

Hermann Hesse, like Nietzsche, like Yeats, struggled with the angel of celibacy for years and he too became an unwilling eunuch as the sexual gave way to the spiritual. Born in 1877 in the Black Forest town of Calw, the early decades of his life were turbulent, as he rebelled against family and country, the Heimat. He flirted with and rejected suicide, then he fell into marriage in 1904. His novels for the next three decades explored the right way to live, the guru, the saint, Jesus Christ, the Buddha, Goethe's Faust and Nietzsche’s Übermensch, masculine heroes confronted by the Eternal Feminine. (George Bernard Shaw - Man and Superman, 1904-5 - was thinking along similar lines in Britain.)

One day in 1907, at his home in Gaienhofen in southern Germany, Hesse encountered four long-haired hippies led by the German guru, Gustav Gräser. Hesse was 30 and frustrated. Before long, he found himself walking with them all the way to Ascona, near Locarno in Switzerland, spending several weeks sleeping in caves in the Alps. It was a revelation. At the time Ascona, or at least Monte Verità, above the town, was a pilgrimage site for European New Agers. On this Magic Mountain European intellectuals relived the lifestyle of the ancient pagans, those “Here Comes the Sun” Teutons. It was really intellectuals copying what the idle rich had always done when they visited spas for “the waters” except that now the intellectuals dined on salads and cereals and wore fewer clothes. The locals thought they were all crazy, but Hesse was able to cure himself of his alcoholism while he was there.

In 1911, at the age of 34, he did it again. He just up and left his wife and children and made what turned out to be a disappointing trip to India (stomach problems, the heat). Hesse had been born into a Lutheran missionary family who served in India and his mother was born there, so India (and later China) would always retain a spiritual dimension for him. It was an imaginary place to which he could escape intellectually, in the German Orientalist tradition of Schopenhauer, Wagner, Jung or Keyserling. All his novels are pilgrimages, spiritual autobiographies, just as Lennon’s songs are autobiographical where McCartney’s are not.

During World War I both Hesse and his wife suffered breakdowns. Hesse was nearing 40 when he checked into a sanatorium in 1916. The gurus of psychoanalysis would provide a path out of the darkness and result in his great novel of 1919, Demian, with its explicit Nietzschean and Christian motifs.

In 1919 Hesse finally left his wife, deposited the children with relatives and moved to Lake Lugano in Switzerland for good. It must have been a difficult choice for him, and it comes across as running away, but it was understandable. It found expression in Siddhartha (1922), which is a beautifully composed and tranquil novel and arguably his best work. The Christian mountain becomes a Hindu river and there have been many debates about whether Siddhartha’s message is actually Buddhist or anti-Buddhist, Indian or Chinese, about a Christian saint or an Übermensch. But Hesse’s essential insight is “This cannot be taught,” which became a constant refrain in his novels after that. Increasingly he came to accept that transcendent reality had its own rules. It was a timeless spiritual world in parallel with our own.

Either way, sexuality reared its ugly head again. One might have thought that with Siddhartha Hesse had found a way to live his life satisfactorily, but Kamala the courtesan is based on the Kama Sutra after all. Though Siddhartha gives her up, Hesse made another unsuccessful (and short-lived) marriage in the real world of sexuality. This disaster worked its way into the amazing Steppenwolf where Hesse comes to terms with the destructive urges (his sense of guilt, his loneliness, his frustration). It was only when he was in his 50s that he made a good marriage and found peace of mind and a sense of humor, becoming a master of the glass bead game.

But to do so, Hesse had to become one of Nietzsche’s eunuchs, for his writing became all form and no emotion. Ironically, Hesse’s English translators contributed to this by minimizing his sexual metaphors. At any rate, for Hesse, life, like art, becomes abstract as you grow older and cross into the spirit world. This is Goethe's great insight with Faust. It seems to be what all Western saints or Eastern gurus aspire to; no wonder elderly literary critics love The Glass Bead Game the most. They too desire to live spontaneously outside time and space in the realm of the eternal feminine. Moksha.

Across the Universe

Hesse lived out the Christian or Buddhist or Schopenhauerian notion that suffering/saṃsāra is the human condition. On the political side such ideas found their way into the Faustian writings of Oswald Spengler (The Decline of the West) and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck (The Third Reich), eunuchs both. In poetry, Yeats said it best: “Now days are dragon-ridden/The nightmare rides upon sleep.” “We had fed the heart on fantasies,/The heart’s grown brutal from the fare.” With the horrors of war these things are always personal. But one could equally ask whether celibacy predisposed these intellectuals to an ascetic and pessimistic philosophy of life. No orgasms, no cigar.

In the West, gurus and saints faded somewhat in the 1970’s and 1980’s (maybe secular shrinks grew in number), because they simply went out of fashion, as Lennon did, as Hesse did, as India did, as Rajneesh/Osho and the Maharishi did, as religion did. All the big ideas did. Even orgasms did since now they were widely available. It was a function of prosperity and affluence. Joseph Campbell came into his own during this time, with his influence on George Lucas’ Star Wars (Campbell died in 1987) and that is because mythology always comes into vogue at the end of something, not the beginning. Mythology is just the academic equivalent of mystical or Gnostic thinking in popular culture.

Nowadays we have talk show hosts and the therapy crowd purveying New Age Gnostic ideas – it accelerated with The Da Vinci Code, The Secret, MAGA, QAnon, Covid vaccines – which are all about a “secret code” and a conspiracy to hide it? Lost secrets, red giants collapsing into white dwarfs, the Magdalene’s bloodline... It all sounds like Wagner’s Ring operas or the Rosicrucians' spiritual alchemy or Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. But, these ideas surface in every generation. If the West is turning in on itself, in one of its centripetal swings, it has done it before and it will do it again.

Joseph Campbell and Chartres

Joseph Campbell didn’t get to visit India until 1954 when he was 50, after spending decades reading about it. In his book Baksheesh and Brahman he offers many insights but he also reveals paternalistic attitudes that took him decades to cast aside. Brilliant though he was, he became the latest in a long line of Orientalists. Couldn’t this quote from The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) refer to Campbell in India? “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.” Campbell went back home and wrote about it.

As with Hesse, Campbell’s psyche was rooted in the West, in medieval Christian mythology. When he was a student in Paris, he visited Chartres Cathedral. If we ignore a sexually ambiguous encounter with a priest, it seems that Campbell experienced something profound in viewing the sunlight streaming through the stained glass windows of the old Gothic cathedral. For Campbell this was “the womb of the world” and he was experiencing the presence of God. He cited it enough times in his writing for us to know that it was a special moment. (I have read of tourists who have tried to duplicate Campbell’s experience at Chartres and have come away disappointed.)

As he grew older he came to embrace his own monomyth of the questing hero. If mythology is also autobiography, then Campbell fancied himself as Merlin, the ancient and wild Celtic magic man, a Hierophant, a latter-day saint who was domesticated by the cult of the feminine he found at Chartres and in the Kundalini he found in India. Nietzsche would have hated it.

If that sounds unfair, and many academics loathe such reductionism (which is why it is so worthwhile), then Campbell is redeemed to a large degree by his sense of mischief when he compares religions and cultures. That led to charges of anti-Semitism, of course, for Campbell was all about attacking what he perceived as religious pretension and Judaism certainly wasn’t immune from it.

But sex has always been the wild card.

Campbell and his wife never had children. That decision, presumably deliberate, is fascinating. His wife, Jean Erdman, told one of the Honolulu newspapers: “Fortunately, he didn’t want any children, because he thought it would take too much time and focus away from his work, and I just wanted to dance. We both decided our students were our children.” This seems like a cop-out for a man who once said: “A male and female coming together with the possibility of another life coming out of it – that’s a big act.” Campbell ended up living a monastic life, as many academics do, as Hesse did, as John Lennon might have done if he had passed 40. The Bible sums it up best:

For there are eunuchs who were born that way from their mother’s womb; and there are eunuchs who were made eunuchs by men; and there are also eunuchs who made themselves eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven. He who is able to accept this, let him accept it.” (Matthew 19: 8-12)

All You Need is Love

So who needs gurus, saints and heroes these days when we have Bollywood? In the last decade, Bollywood has invaded Western television and cinema screens as well as YouTube and other social media with its rapturous celebrations of sex and romance, following the path of Indian immigrants in past decades. In today’s Bollywood movies, soap operas and music videos you have to be under the age of 25 and Westernized and sex is everywhere. Gita Mehta had mixed feelings about it; perhaps Mira Nair and Gurinder Chadha embraced it with their own Kama Sutra, their own Bride and Prejudice, and Deepak Chopra issued his interpretation of the Kama Sutra (which includes the Seven Spiritual Laws of Love!), and in 2008, Slumdog Millionaire won the Oscar! Of course, India has also been the land of Godfather-style gangland killings, horrific gang rapes and Bharatiya Janata religious and sexual conservatism, where Bollywood films stir up accusations of immorality and court action. In 2007, well before the 2014 election that brought the BJP to power, effigies of Richard Gere were burnt after he kissed Shilpa Shetty provocatively at an HIV/AIDS awareness event in New Delhi. He was charged with indecency and so was Aishwarya Rai a week later for a peck on the cheek.

Still, in the West, as in India, there is no New Age cosmic sexuality vibe attached this time: mostly it is Indian guys and girls just want to have fun. Say Shava, Shava and Shakalaka Boom Boom and Jai Ho all together now! All you need is love, baby…