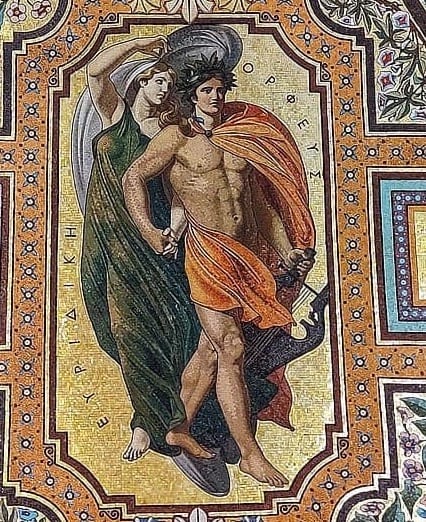

Orpheus and Eurydice

The legend of Orpheus and Eurydice once fascinated artists, perhaps because it questioned our understanding of death, from which we are so isolated today, and because it asked whether music and song could heal us. Orpheus goes to the land of the dead and returns, albeit in the end without Eurydice. From classical times onwards it offered a template on which artists could project their own feelings on the matter, since everyone loses a wife or a husband or a child or a friend and wishes for their return.

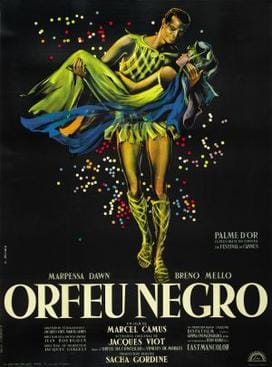

These projections have ranged from the highly critical or gloomy (Plato, Virgil, Ovid, Pausanias, Dürer, the Brazilian film Black Orpheus) to the redemptive (Ficino, Monteverdi, Rubens, Poussin, Gluck, Cocteau), to the racy and sexual (Offenbach, Rodin). Surprisingly perhaps, not much of the painting is any good. Albrecht Dürer's unhelpful contribution was that after losing Eurydice, Orpheus turned to boys and that's why he was killed by angry Thracian women (The Death of Orpheus, below, is from 1494). But then maybe he was just copying an Andrea Mantegna painting.

For the redemptive storytellers, the story fitted easily into the dominant pastoral mode, which always has been about coming to terms with loss, not the simplistic idea that the world is always in spring. Many musicians' works celebrated life over death, which makes sense since divine music was Orpheus' great talent - in Monteverdi's Orfeo, for example, which built on the Jacopo Peri/Giulio Caccini opera Euridice of 1600.

The roots of this were Neoclassical. Below is an exquisite pastoral fresco showing Flora (Roman goddess) of Primavera (Spring) from Stabiae, a popular resort town of the Roman era. It was found in the excavations of the Villa Arianna and it is now at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. Stabiae was destroyed at the same time as Pompei, in an eruption by Vesuvius in 79 AD. The painting is particularly evocative of the pastoral theme of so much of the painting and music of the 16th and early 17th centuries.