Oz is China

A Political Fable of Chinese Dragons and White Tigers

A Political Fable of Chinese Dragons and White Tigers

JOURNEY TO THE WEST: WHY OZ IS CHINA

Once upon a time, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a purely American tale. Nowadays, almost nobody knows that in L. Frank Baum's original novel of 1900, there is a chapter called “The Dainty China Country” and in the China Country there is a Great Wall… And once Dorothy has climbed over it, its China people resent the intrusion of the foreigners, the yang guizi, there is violence and they are forced to leave. This isn’t in the film of 1939 of course and that’s the only yardstick anybody really knows; and certainly nobody reads the original novel. In 2013, China Girl did appear in Oz the Great and Powerful and the film proceeds to destroy her country and her people, but does anyone remember?

At any rate, these events bear an uncanny resemblance to events in China at the end of the 19th century, the years of the Boxer Uprising, and the same years in which the Baum book was written. It all makes sense if you know that Oz was really China.

Historically, we know that the Empress Dowager CiXi took advantage of the Boxer Uprising, seeking to drive out the foreigners pretty much the way it happens in Baum’s China chapter. With hindsight, we know that the foreign devils called in the gunboats, and the uprising was suppressed.

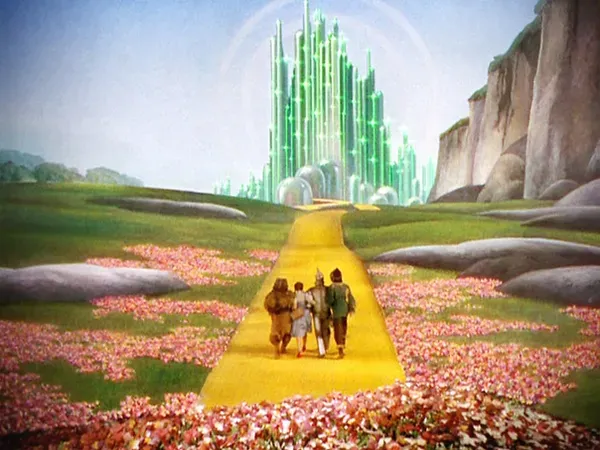

Others have commented on this resemblance but what if it wasn’t just this chapter? What if in fact it was the whole book? What if the Emerald City was really The Forbidden City? What if the Wizard of Oz was under house arrest rather like China’s Jade Emperor? In China, the Guangxu Emperor was under house arrest because the Empress had effectively seized power from him in a coup d’etat of 1898. Like the Wicked Witch of the West! Baum later would rename CiXi as Queen Zixi of Ix, but, CiXi or Zixi (or Tzu-Hsi as Baum would have known her), the resemblance is unmistakable. So couldn't that mean that the Yellow Brick Road was really the Yellow River, the great highway that flows through northern China, or could it be the prestigious golden bricks of the Ming dynasty, which were produced in Suzhou? Yellow was the color of the Chinese emperors, the color of earth, the color of life.

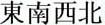

And why not? There are clues everywhere. Pick up a copy of the book and you will see a red Chinese lion woven around the word OZ on the book cover. And remember those poppy fields Dorothy encounters? In the 19th century, Britain fought two wars with China over the lucrative opium trade (Britain sold opium to Chinese addicts and cynically pocketed the proceeds). In the U.S. there were regular police raids on opium dens.

Not convinced? Baum read the newspapers avidly and he was consumed with news from China. Indeed he was a former newspaper man and he followed the rapid deterioration of events there throughout 1898 and 1899 like everybody else. He was very well aware that the U.S. had seized Hawaii, that there were 70,000 American troops fighting in the Philippines and that American missionaries were among the dead in China. He found himself deeply ambivalent about the use of military force but he didn’t ridicule it the way Mark Twain, his contemporary, did. (The following year more than 3,000 American troops participated in the international army that occupied Beijing in August 1900, led by the U.S. 14th Infantry, the Golden Dragons. The Philippines would become the Iraq of a century ago, while China would fall into chaos.)

鬼子

Baum finished writing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in October of 1899, in parallel with illustrations by W.W. Denslow. For those who will pick up a copy of the original novel and look at Denslow’s illustrations rather than relying on updated editions or the film, you will see much to startle you. The diminutive inhabitants of Munchkinland in Denslow’s drawings, with their long beards and shaven heads with little topknots of hair resemble awful American cartoons of Chinese during the late 19th century, leading up to and during the Boxer Uprising (if one overlooked the peaked hats). When Baum writes: “The Wicked Witch was angry to find them in her country,” the illustration shows her dressed in Manchu pigtails, her imperial regalia and her Golden Cap – the Empress Dowager in all her glory.

Many people spotted this when the book came out. The Boston Beacon wrote, in September 1900, that “the Scarecrow wears a Russian blouse, the fierce Tin Woodman bears a striking resemblance to Emperor Wilhelm of Germany, the Cowardly Lion with its scarlet beard and tail tip at once suggest Great Britain, and the Flying Monkeys wear a military cap in Spanish colors.” I had pegged the Flying Monkeys as Chinese Imperial troops but I will defer to the Beacon. As one contemporary historian has noted, “The papers were full of xenophobic reports from China… In November 1900, Denslow issued his own satire of the conflict as a color print titled ‘The Heathen Chinese,’ depicting three boys dressed for war, representing the Western powers, who threaten a small grinning Chinese doll.” Baum, it must be said, was a little more subtle than Denslow. (Source for the quotes above: Michael Patrick Hearn in his excellent The Annotated Wizard of Oz. Hearn also spots the connection to the Boxer Uprising but only in the “China” chapter.) It also should be noted that when Ruth Plumly Thompson set out to write the first Oz sequel after Baum's death in 1919, she sets The Royal Book of Oz (1921) in a place that looks like China, where the Emperor is Chang Wang Woe!

But, back to Baum: in the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West, four travelers go West in search of enlightenment before returning home to China. As Jonathan Cott has pointed out, isn’t that also the story of The Wizard of Oz? (There is even a Toto in Journey to the West, a little white dragon who acts as the main character’s horse.) But that novel was a fusion of Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism. Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman and the Cowardly Lion belong in a culturally Christian and imperialist context. Was Baum making a point about the tens of thousands of Christian missionaries who poured into China during the 19th century, many of them Americans, bent on exterminating its witches and exposing its wizards. They left a lasting legacy and it’s fair to say that they displayed few brains, but they also showed a lot of heart and undoubtedly a lot of courage.

So, was Dorothy the leader of an alien cult, a xie jiao? Was she just one more fanatical witch exterminator? In this the “Chinese century,” can the Chinese also claim The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as their own?

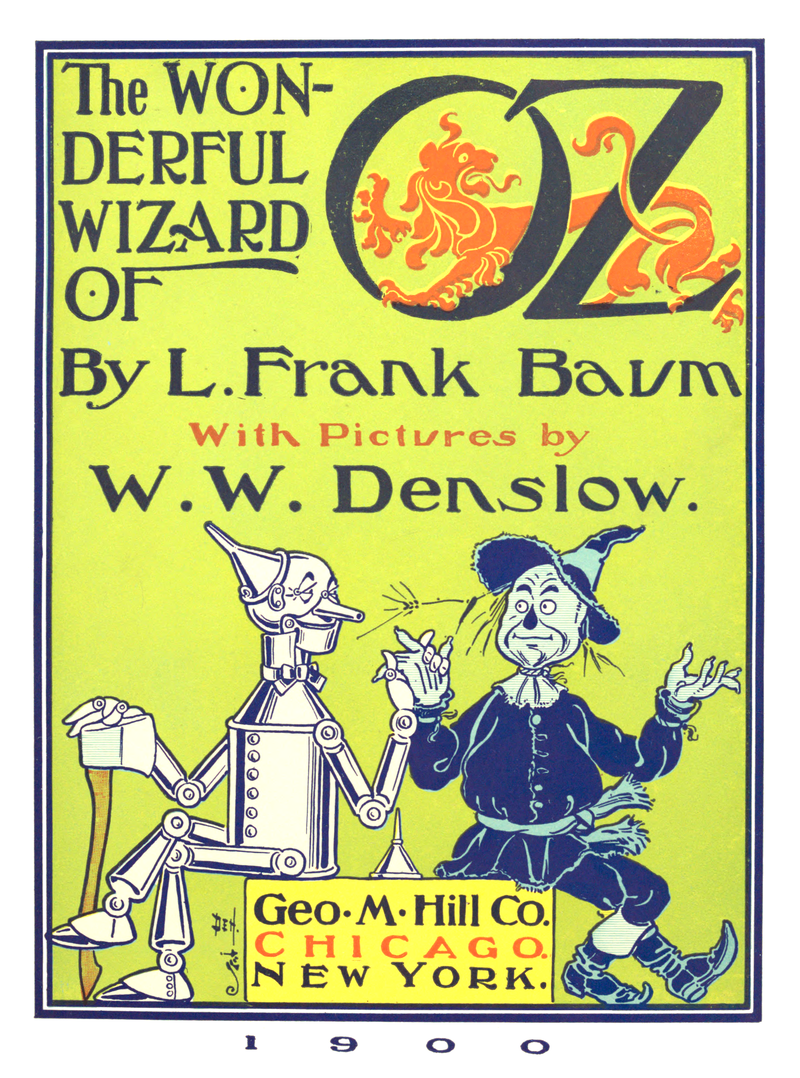

WATER MARGIN: PEARL S. BUCK AS DOROTHY

In one of those strange twists of fate that history throws up, a young American girl exactly Dorothy’s age (6 years old) was growing up in China when The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was written. That little girl – Pearl S. Buck – was the child of a Christian missionary family in Zhenjiang, far to the south down the Grand Canal. It was a momentous time in China: two German missionaries had been murdered in Shandong and Pearl’s father risked his life preaching in outlying villages. As the Boxer Uprising intensified, Pearl and her family were forced to flee to Shanghai. It was there that she read The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, fresh off the boat from America. Pearl was too young to grasp it at the time but, as her Confucian trained teacher later pointed out, the real message in Baum’s novel was that foreign devils ought to be sent home.

Pearl, like her teacher, immediately spotted the resemblance between the Emerald City and The Forbidden City. The Wizard of Oz was holed up like the Chinese emperor Guangxu, imprisoned in the Hall of Jade Ripples after the coup d’etat of 1898. The true power in Oz was now the Wicked Witch of the West, unmistakably the Empress Dowager, Cixi, the Imperial Dragon Lady, presiding over the collapsing pack of cards known as the Qing dynasty. Cixi herself occupied the Western half of the Forbidden City and this qualified her as the Wicked Witch of the West. (There once had been a Wicked Witch of the East, or rather an Empress Dowager of the Eastern half of the Forbidden City, but Empress Ci’an had passed away in 1881, and regrettably not from Dorothy Gale’s mobile home crash-landing on her in the flowerbeds of Shandong.) The surviving Wicked Witch had a weak spot, for the thing she feared the most – that which could destroy her – was the floods. In 1899 the Yellow River flooded enormous areas of northeastern China. The omens of the gods were foreboding. Had she lost the Mandate of Heaven?

Pearl wondered about other resemblances in the novel. There were those 40 wolves and 40 crows, the bees, the fearsome Flying Monkeys and the Hammerheads… Who were they but the Boxers, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists? In a way, the magic mark on Dorothy’s forehead recalled the Boxers’ belief that they were Immortals, protected from the foreigners’ bullets. Then there were the fierce Kalidahs; were they the bandits of Liangshanbo? As an adult writer, Buck was drawn to that classic Chinese story, known now as Water Margin, and which she translated as All Men are Brothers (1933).

After the Wizard was unmasked, Dorothy and friends journeyed south to the Quadlings’ country. None of this is in the movie, but the Quadlings seemed like southern Chinese businessmen lining up to trade with the foreigners in Hong Kong, Macao and Amoy. If the Quadlings were always far enough away from imperial Oz that they didn’t feel threatened, the Munchkins and the Winkies, on the other hand, had been enslaved by the Witches in low paying factory jobs and indentured labor on the farms of Oz. Now that they had been rescued, they seemed only too keen to have the foreigners rule over them! In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Dorothy’s friends all end up with territories to run: the Scarecrow gets to rule Oz from Beijing, while the Tin Woodman calls himself emperor of the Winkies (just like the Kaiser, who decided to open a brewery there).

In later years Buck would come to see The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as a gentle satire on Western imperialism and the Christian civilizing mission in China. She publicly (and controversially) repudiated the missionary enterprise in the early 1930’s, but she never lost her optimism that the West (and Christianity) could benefit China, seeing it as a reciprocal relationship. She believed that if Dorothy had a good heart, an open mind and plenty of courage, then China would respond positively. Like Baum, Pearl S. Buck was Dorothy all right.

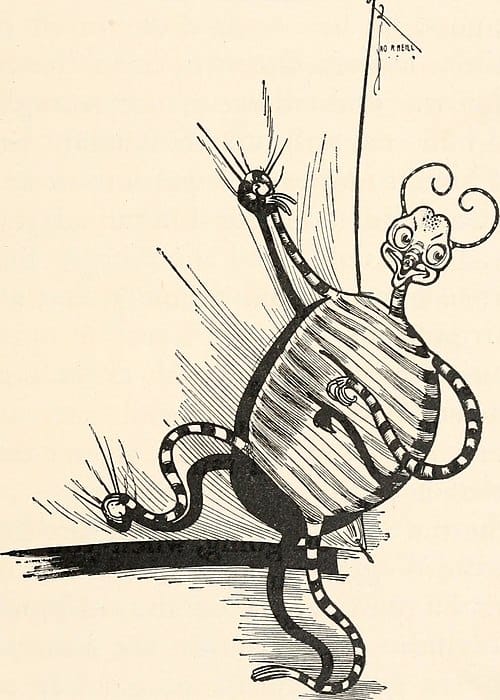

If Buck was determined to upset conservative evangelicals, her ability to read and write allegorically also enraged the liberal intellectuals. These were the very same people who had scorned Baum as a writer of children’s literature and Baum took his revenge by parodying them with the Woggle-Bug - shown below. When Buck won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938, the literati poured scorn on her and she retaliated. In The Chinese Novel (1939) Buck’s real target was living in the United States, not China: “There, literature as an art was the exclusive property of the scholars… They were powerful enough to be feared even by emperors, so that emperors devised a way of keeping them enslaved by their own learning… (The scholar) was not to be seen except at literary gatherings, for most of the time he spent reading dead literature and trying to write more like it. He hated anything fresh or original, for he could not catalogue it into any of the styles he knew.” She could have been referring to William Faulkner, who had dismissed her as “Mrs. Chinahand Buck.”

So we have the three B’s: Baum, Buck and Bradbury. Ray Bradbury writes of Baum: “Everyone goes around democratically accepting each other’s foibles in the four lands surrounding the Emerald City, and feeling nothing but amiable wonder toward such eccentricities as pop up.” If you put aside the genocide of Native Americans, native animals and native flora, what other novel speaks so eloquently about the appeal of the American Dream, the pushing West to the frontier, the City Beautiful, and the belief that there really is no place like home?

SIX RECORDS OF A FLOATING LIFE: ANNA MAY WONG AS DOROTHY

Anna May Wong, the most famous Asian-American actress in Hollywood, has been the subject of a recent wave of rapturous articles and biographies and deservedly so. Born in 1905, five years after The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was published, she discovered during her heyday in the 1930’s that part of being American means coming to terms with your “inner Dorothy.” So we could say, and should say, that Dorothy was also Chinese American.

Her Dorothy moment – we all have Dorothy moments – was in 1936. She was 31 years old. For a long time, China had been a distant dream for her: “Far to the westward lay China, the country I have known only in shadowy dreams,” she wrote. She and her sister Lulu set sail early in 1936 and spent most of the year there, visiting Shanghai, Hong Kong, Beijing and, crucially, their ancestral town in the Pearl River delta, west of Hong Kong (where it is said that almost 75% of overseas Chinese come from). Everywhere she went she was greeted as a major Hollywood star, and indeed she was, for all of her films were marketed to Chinese audiences as if she were the lead.

On the other hand, she also realized she was culturally an American when, in Shanghai and elsewhere, she was berated for her role as a prostitute in the 1932 film Shanghai Express with Marlene Dietrich. How dare she be a traitor to China, they said, for allowing herself to be used by the movie studios to embarrass China. Later she would write wistfully: “It’s a pretty sad situation to be rejected by the Chinese because I am too American.” It was a complex moment. Shanghai was exciting, a vibrant city full of White Russian and other prostitutes, which the movie reflects, but many Chinese naturally resented the fact that these exclusionary “concessions,” where Europeans and Americans holed up, were off limits to Chinese. A prostitute symbolized everything that had gone awry. There is some synchronicity here too, for Pearl Buck’s novel The Good Earth had been met by the same hostility there back in 1932 and she had been forced to leave China in 1934.

(Interestingly, before Wong went to China, she had gone East to Europe during the late 1920’s. Unable to gain the recognition in Hollywood that she wanted, this party girl and sophisticate mixed in easily with the celebrity crowd in London and Continental Europe, scoring many roles on screen and teaching herself French and German in her spare time so that her films didn’t need to be dubbed. There was a lot of Dorothy in her.)

But it was only after her pilgrimage to China that the party girl sophisticate was at ease with her ethnic and national identity as a betwixt and between, and therefore better able to come to terms with having not gotten one of the two plum roles in the MGM film of The Good Earth. The rejection had come before she left for China and the parts eventually would be played by white actors Paul Muni, Luise Rainer (who won the Academy Award for 1937 for her performance) and Tillie Losch. The idea that only Caucasians should play Chinese for fear of breaching Hollywood’s Production Code (which banned miscegenation) seems ridiculous these days, but then so does the idea that Chinese actresses should play lead roles in Memories of a Geisha. The tin woodsman’s ear…

Racism against Chinese had been around for decades of course. In 1871, Chinese immigrants had been set upon and murdered by a white mob in Los Angeles’ Chinatown. Periodic lynchings of Chinese men occurred around the country. As matters worsened in China in the late 1890’s and the worst atrocities received heavy coverage in American and European newspapers, there was a distinct change in the representation of Chinese. To meet a surging public appetite for more stories to make sense of it all, pulp fiction and dime novels picked up on the theme, to be followed shortly after by the silent movie serials. One of the most successful was The Yellow Danger in 1898 by British writer M. P. Shiel, subsequently renamed The Yellow Peril, after the Kaiser famously coined the term the same year. This was the environment in which Baum was writing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and he was not immune to its influences, neither the appeal of writing escapist science fiction nor the temptation to use crass racial stereotypes. Baum, after all, had contributed the following ditty to his children’s anthology Father Goose, which was published before his more famous novel:

Lee-Hi-Lung-Whan

Was a little Chinaman.

Wooden shoes with pointed toes,

Almond eyes and tiny nose.

Pig-tail long and slick and black,

Clothes the same both front and back.

Funny little Chinaman,

Lee-Hi-Lung-Whan.

Anti-Chinese stereotypes remained prolific for decades to come. The diabolically evil Dr. Fu Manchu first appeared in 1912, the creation of yet another British writer, Sax Rohmer. Here the link takes us back to Anna May Wong who would star in the lead role of one of the film adaptations of Fu Manchu stories, Paramount’s Daughter of the Dragon in 1931. Wong, the daughter of a Chinatown laundryman, who had got her first film role at the age of 14 as an extra in a film called The Red Lantern, set during the Boxer Uprising, now played dangerous Oriental temptresses and femme fatales. It is interesting to think of her as living just across town from L. Frank Baum at the time. It is less interesting to think that she made her career out of playing dragon ladies and courtesan fox fairies, dying a thousand deaths in the final reel, but never getting her man.

Anna May Wong never married.

Later in life she performed in a stage version of Princess Turandot, became a Christian Scientist and continued to read widely. Although none of the biographers really grapples with it, her death in 1961 was from a disease of the liver. Such diseases are usually from drinking too much alcohol. Is that how it ended? Dorothy drank her way to yangsheng, to immortality?

FLOWERS IN THE MIRROR: EMPRESS CIXI AS THE WICKED WITCH OF THE WEST

So, is The Wonderful Wizard of Oz really a fable of Christian innocents abroad in China? The very idea is hilarious and ridiculous. L. Frank Baum was a hopelessly unenthusiastic Christian, who found his mother’s devoutness extremely irritating and he found refuge in the alt-Christian theories of the Theosophists and spiritualists. But, culturally and historically, he was a Christian and his books celebrate Christian values while gently mocking them. (There always has been a blind spot among Western intellectuals, failing to see the cultural context in which they live, believing that their values are somehow universal, and Baum’s critics have been no different.) The novel articulates many of the great New Testament themes: good versus evil, Jesus and the disciples as strangers in a strange land, the spiritual journey toward salvation, the power of conversion and redemption (even if the Wizard is a humbug, a woggle-bug). More a Protestant or LDS dream than a Catholic one.

When Baum was writing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, he did not have Twain’s foresight to see that things would go horribly wrong for Oz and for Christians in China. The real focus of the Boxers’ animosity, and what allied them with the Empress Cixi, was their hostility towards Christianity, for the simple reason that it symbolized the West. Christian missionaries had, throughout the 19th century, introduced Western expertise in agriculture and medicine, built hospitals, orphanages, schools and universities and linked China to the international community. They had taken strong moral positions opposing the opium trade, footbinding, prostitution and the like. All very impressive and, as a result, Christianity had a strong appeal to certain sectors of the elites, who saw it as a pathway to advancement, either in China itself or abroad. However, as with the Middle East today, it could never be severed from its debilitating association with imperialism, the occupation of Chinese land, and the patronizing attitudes of the Western powers.

The figures vary but most agree that during the Boxer Uprising around 231 foreigners were killed, of which 53 were children (according to one source) and almost 20,000 Chinese Christians were killed. But one Chinese source says the death toll throughout northern China was as high as 100,000. Some perspective is required here. These numbers are nothing compared with the millions who died in the Taiping Rebellion (although that was partly Christian-inspired), or the Nationalist-Communist civil wars and internal purges, or the utter catastrophe known as the Great Leap Forward, during which many tens of millions died.

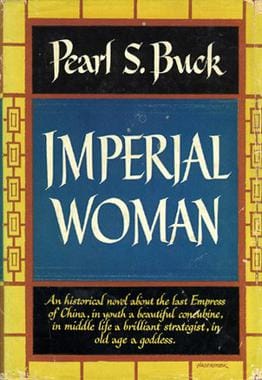

Many years later Buck would write a favorable portrait of the Empress CiXi in Imperial Woman (1956). While much of it reads as conventional historical novel, her handling of the Boxer Uprising reflects her view that events went quickly beyond the Empress’ control. This is also the view of her Wikipedia biographers who currently are trying to come up with a portrait of her that is less tinted by the green spectacles of Western propaganda. Other writers have been less kind: Lao Shê explored the same theme in his play Chaguan (“Tea House”), which was written the following year, in 1957. The events are set in a Beijing teahouse in three different periods. In the first, in 1898, a tale is told of how a huge spider had turned into a demon and was then struck by lightning, which is pretty much what happened to the Empress. There was also talk in the teahouse of how it might be a good idea to build a Great Wall along the coast to keep out the foreign troops. They came in anyway. (As one who understood satire and allegory, Lao Shê was, sadly, a victim of the Cultural Revolution, drowning himself in 1966.)

In today’s China, the Boxers have been rehabilitated as patriots who fought the imperialists, while CiXi is coming to be viewed much the same way. If she was the figurehead of the corrupt and collapsing Qing dynasty, at least she was (more or less) Chinese. Nowadays you can still be vilified in China if you dare to say there was plenty of blame to go around.

There is a story that when the Dragon Empress CiXi died, a huge pearl was placed in her mouth to protect her corpse from decomposing. That pearl apparently made its way to Chiang Kai-shek who gave it to his wife and it ended up as an ornament on his wife’s silver shoes. I would like to think those were the same silver shoes of the Wicked Witch of the East that fell off Dorothy’s feet as she was leaving China...

THE TAO TE CHING:

THE FENG SHUI OF OZ

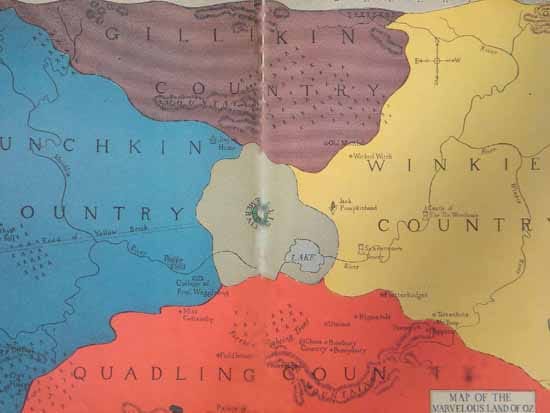

There is a mystery that long has obsessed Oz historians. The mystery is why the famous Woggle-bug map of Oz reverses East and West. There has never been a satisfactory explanation for it, other than speculation that Baum wanted to mock the Woggle-bug’s learning. As anyone who has studied the cartography of Oz knows, all the existing maps are notoriously unreliable, most notably this one, but why get such an obvious thing wrong?

Once we accept that Oz is China, the whole puzzle begins to fall into place. Baum conceived of the map of Oz in the shape of a flag with quadrants and Oz was at the center. By reversing East and West, was Baum trying to conceal the fact that he was actually writing about China, to deny the fact that he was influenced by Buddhist ideas of the Navel of the World? No. The answer is even simpler than that. In Chinese maps, East is on the left and the West is on the right when the world is viewed from Beijing!

If you, the Western reader, are somewhat adrift at this point, remember that the world as seen from China is governed by the rules of geomancy, not Mercator cartography. What we understand as West on the left and East on the right is reversed, since it is viewed from the perspective of looking from the North, not the South. This of course reflects the view of the Emperor in Beijing (紫微星).

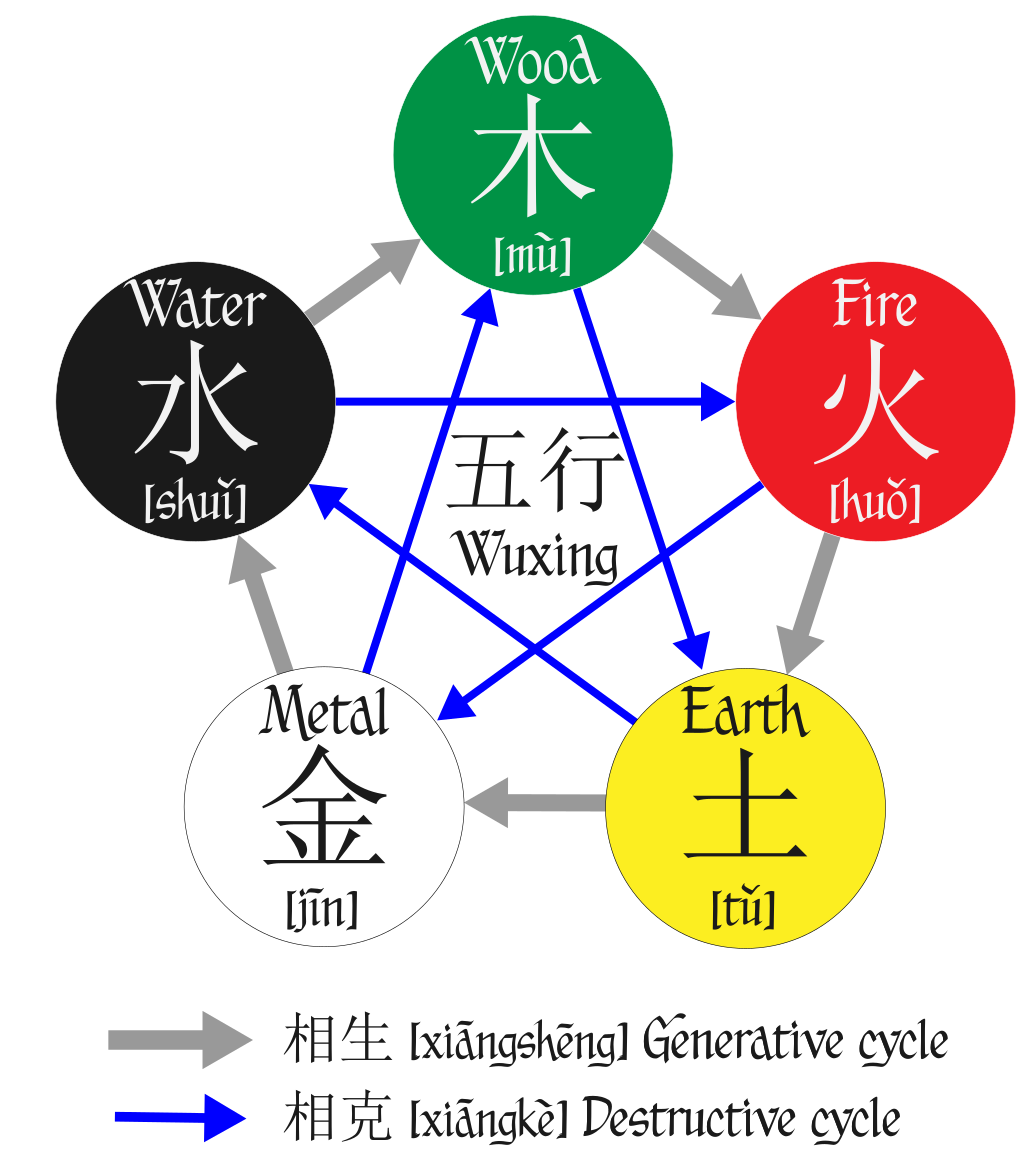

It is not exact, because yellow has moved to the center and replaced by white. Even so, blue Munchkinland can be Shandong and eastern China, purple/black Gillikinland is Manchuria, the Winkie Country is western China with its yellow/white dust landscapes and the Quadling Country is the red earth of southern China. This design accords with the Wuxing 五行 (Five Phases) and the Buddhist concept of a mandala (and Baum’s Theosophist beliefs) in the division of nature, which is why the Emerald City is in the center.

This arrangement matches the ways China has traditionally been regionalized and mythologized around the elements and colors (and numbers) and the figure of the Jade Emperor: yellow, red and purple were all associated with the emperor and blue was the color of Heaven. Green in the center was life itself. Beijing's Forbidden City features a splendid array of all these colors. The Qing (Manchu) dynasty military divisions used color banners to denote their eight imperial armies and then there was the Green Standard Army, the Green gangs of the nationalists, Chiang Kai Shek’s Blueshirts and Mao’s Red Army, the White Lotus Society and the triad colors… Has a nation or an empire ever celebrated color coding as enthusiastically as China?

In traditional Chinese mythology, the East is guarded by the Azure (Blue) Dragon, referring to Spring, sunrise and the Sea (shown below). It was here in the East that the Westerners arrived in force. (The West is guarded by the White Tiger, referring to Fall and sunset. To the North is the Black Tortoise, representing Winter, and to the South is the Red Bird, representing Summer.) In feng shui, things can become out of balance if the Azure Dragon’s realm is overwhelmed by the White Tiger and that is what happened, for Dorothy was in fact a White Tiger entering from the East instead of the West. One could say that destruction would surely follow, as surely as the tornado that destroyed Dorothy’s very bad feng shui Kansas home.

Naturally this puts the Munchkins’ fear and adoration for Dorothy in a whole new light. If White Tigers traditionally were regarded with alarm, for seeing one generally signified disaster to come, then Dorothy’s sudden appearance came across as a powerful and determined Yin (female) presence in traditionally Yang (male) territory. Worse, the White Tiger and the imperial Dragon were, on this occasion, both women!

As The Tao would say:

A way that can be walked

is not The Way

A name that can be named

is not The Name