A Tale of Two Women

Malinche as the Virgin of Guadalupe

Malinche And The Virgin Of Guadalupe

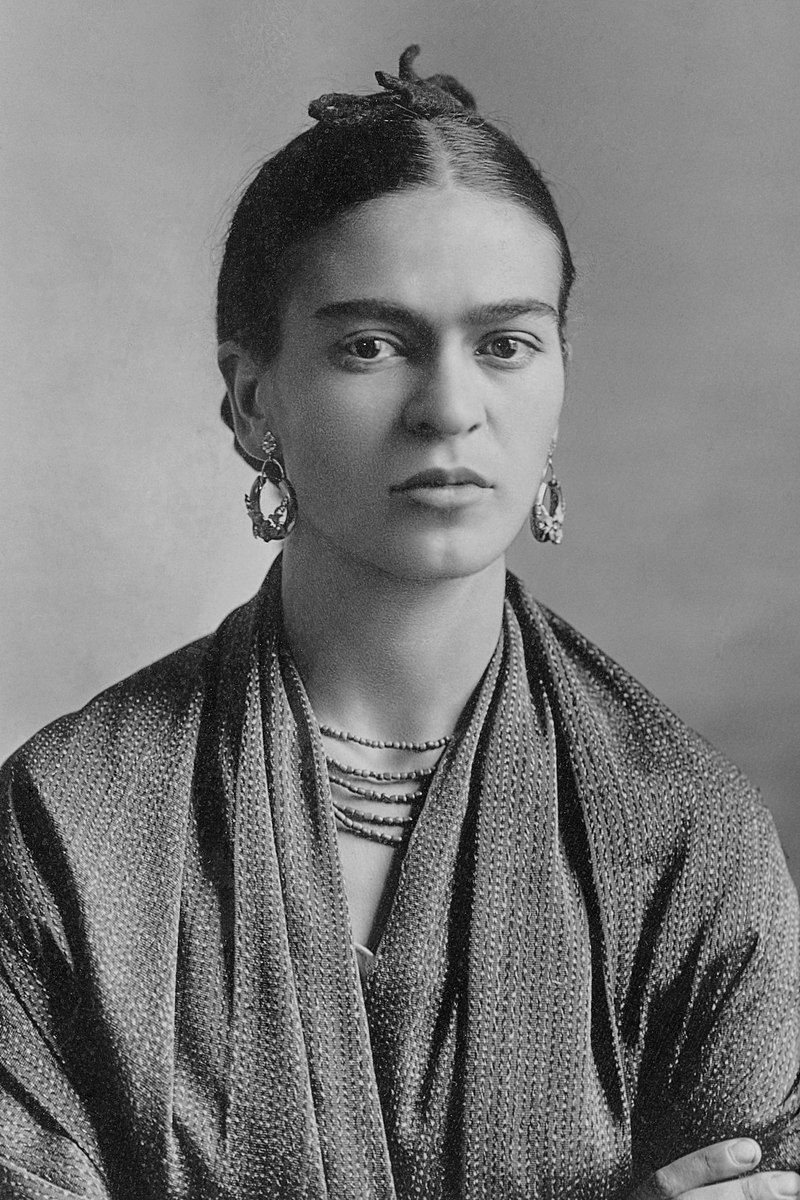

Carlos Fuentes was right, at least in the beginning. In his introduction to Frida Kahlo’s diary, he describes her arrival one evening in the opera box as an apparition of Coatlicue, a jangling and magnetic performance by an ancient Aztec earth goddess. He is proud of her, nonetheless! She expresses México’s fierce national identity, its pride, its secret hurt, its flamboyance and its fabulous fashion sense. But then he goes on to talk about her pain, her defeat, her sacrifice and the purification of Malinche’s sins via the Virgin of Guadalupe. It is Frida’s sexuality and her childlessness, served up with the promise of redemption, those swirling waters that threatened to drag Frida down throughout her life. Talk about sticks and stones...

Octavio Paz was more direct. He called Kahlo “a despicable cur.” And so into the darkness we go with Kahlo as Malinche, Eva, Celestina, la Llorona, the Weeping Woman, la Chingada, the fucked woman… That old mother, she’s a whore really. She sold herself to Stalin. Isn’t it telling that so many of those persecuted by the Inquisition were women? Paz joins its legions as a 20th century Grand Inquisitor.

Kahlo despised this kind of thinking. She identified with Malinche, of course, and Diego Rivera knew it, which may be why his mural of Cortés and Malinche is not nearly as negative as Clemente Orozco’s. Otherwise you would be hard pressed to find Malinche anywhere else in Mexican painting or literature.

Back in the 16th and 17th centuries when México (now Estados Unidos Mexicanos) was founded, the evolution of the mother and the whore paralleled the ups and downs of the Virgin Mary and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. If the Virgin started out passive and loving, as in the madonnas of Raphael, that’s what shapes the 1531 apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe in what is now the northern suburbs of México City. By 1550, however, with the Counter-Reformation and smallpox in full swing, she became associated with La Llorona, a mysterious ghost-like figure dressed in a white shroud, wailing along the streets. It is a striking and hallucinatory image. In some versions she is jilted by a lover; in others she murders her children and then, driven mad by the horror, she runs wildly through the streets calling after her victims like some Chupacabra. In still other stories, she is a ghost who returns to avenge herself upon those who have wronged her.

Were these hallucinations defensive reactions against the brutality of the Conquest? Did they reflect the profound grief as entire communities were decimated by European diseases? Were they expressions of frustration because the Spanish authorities were opposed to the Virgin of Guadalupe? In 1569, the fourth viceroy of México, Martin Enriquez de Almanza, denounced her as a cult for secretly worshipping the Aztec goddess Tonantzin (who resembled Fuentes’ Coatlicue in Aztec mythology). Were certain Spanish clergy participating in a charade to convert the Indians? Guadalupe’s fate was by no means certain during this time; she was a battlefield of the passions.

Back in Old Europe, by the 1600’s, the Virgin Mary had become an avenger, Revelation’s Woman of the Apocalypse, stamping out sin and the Church’s enemies (c.f. Rubens’ painting of 1623-4). It affected poor Guadalupe in México, for when her story appeared in print for the very first time, as late as 1648, she had morphed into a justification for the Conquest, a touch of La Llorona about her.

Ironically, Guadalupe also inspired the Mexican revolutionary politics of the 19th and 20th centuries when her images were carried on the banners of the Hidalgo and Morelos insurgents against the Spanish and the Mexican governments and in support of migrant farm workers in the United States. Guadalupe had her revenge.

Into the 21th century, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe remains enormously popular, appearing on the posters of López Obrador. Yet it has been the nationalist intellectuals who have suffered the most from an identity crisis. Paz, for example, was marooned in the United States and France from 1943 onwards. In his 1948 poem “Himno entre ruinas,” he is nostalgic for a lost mythical past when all that’s left in the here and now are desolate ruins. In his landmark study of Mexican identity, “El laberinto de la soledad,” which he wrote and published in 1950, he characterized Mexicans as hidden behind masks, ashamed of who they are and where they have come from. He may have had Kahlo’s Stalinist mask in mind, but it makes a lot more sense today if read as if it is Paz himself who is lost in the labyrinth.

Flesh and blood women do not appear to have suffered from an existential crisis. Malinche and Frida Kahlo – spanning the biological and creative arc of mestizaje, mestizo and mestiza – are the mothers of the modern Mexican and Latin American identity. As contemporary Chicanas point out, there is pride and strength there, not an inferiority complex. Who but a patriarchal man could think otherwise? Malinchismo...

La Casa Negro – Pedro de Urdemales on Tepeyac

Pedro de Urdemales, honorable Knight of Spain, paused to pick some roses from the rocky path beside him. Curious, he thought, who planted the Spanish roses? Who would have bothered on this barren hillside? A mix of yellows, reds, pinks and whites, poked their heads out from the blackened ruins about him. It was December in the year of our Lord 1531 and it was cold up here when the wind blew in from the mountains. Near where he stood, all that remained of a broken pagan temple to old gods lay, reduced to whispers, a burnt sacrifice to Spain’s invading Christian gods. The ruins were a few years old now and the black rocks had been overrun by scrubby vegetation. He remained a few moments longer as rain began to fall in a mist, wondering if the roses could be used in some way. He needed a better scheme. Four days ago he had met with the woman in Higuera Street and she had outlined her plan to him, but he was the one charged with making it work.

The woman, Doña Marina, had told him how for two days running she had surprised a villager on the hills here at Tepeyac. It had been a strange enterprise. She had dressed herself up to resemble the Virgin Mary, the holy Mother of Jesus, and she had succeeded in terrifying the poor man both times. She told the villager how she had come abroad in this new land, so far from Spain, to see that a new church would be built upon this hill. She had asked him to relate all this to the Bishop, Juan de Zumárraga, and he would make it so. Twice she had appeared and twice the old man had told his vision to the Bishop and twice the Bishop had refused. “Proof is needed,” the Bishop had said. “We need a sign from heaven.” Doña Marina could see that the Bishop was resisting being told what to do by an Aztec peasant. Her informants told her this and she had decided she needed a new plan. That was where Don Pedro came in.

Pedro stamped his feet to keep warm. He had found the villager the day before, quite by chance. Disguised as a holy man, Pedro was traversing Tepeyac when Juan Diego came running toward him, begging him to give his uncle last rites. It occurred to Pedro that if the goal was to create a new pilgrimage site here, then what better way than ensure that the gullible Juan Diego experienced a miracle? Could Pedro pull off healing the uncle? They walked to the uncle’s village Tulpetlac, where Pedro greeted the ailing man, Juan Bernardino, offering him a hechiceria concoction of brandy and other herbs. It was another case of typhus no doubt… But rather than giving the man his last rites, Pedro encouraged the family to strip the bed entirely, explaining that bed lice were the problem. Well, it was a gamble to be sure, but Pedro had learned over the years that lice were responsible for most of the world’s woes and he thought it might work, even if the lice were blameless. The family washed Juan Bernardino and wrapped him in clean dry blankets and sealed the roof from the drizzle. Don Pedro declared sternly that Juan Bernardino would not die this evening and that while only a miracle could save him, it was still premature to pronounce his last rites. Pedro had left at that point to meet with Doña Marina. So here he was now, standing in the rain, wondering if he was being paid enough for all this. He was dressed now as a Knight and he was sure he would be quite unrecognizable to the anguished Juan Diego.

Several hours later the rain had blown away and the sun was out. It was turning into a beautiful day. As planned, Doña Marina met up with Pedro and it wasn’t long before Pedro saw Juan Diego making his way across Tepeyac from the north. Was he trying to avoid the place Dona Marina had appeared before him on the previous occasions? Pedro had half expected it so he positioned himself in a spot where he could join paths with the peasant. After engineering this successfully, they walked together, and Pedro steered him in the direction of Doña Marina. On cue, as she had done before, she appeared before them with the sun behind her, its rays catching the frilled edges of her robes. As luck would have it, a rainbow formed in the distance.

“Juan Diego, you know me well by now. I am Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, the Mother of the True God, through whom everything lives, the Lord of all things,” she declared in Nahuatl to Juan Diego who, by now, was as terrified as on the previous occasions. This beautiful Madonna-like figure descending towards him was enveloped in a blaze of light. She continued, and Pedro admired the smooth delivery even if he had no idea what she was saying, “Listen and let it penetrate your heart, my son. Am I not your fountain of life? Are you not in the folds of my mantle? In the crossing of my arms? Do not let the illness of your uncle worry you because he is not going to die of his sickness. At this very moment, he is cured.” She instructed him to climb the hill to receive the promised sign – Castilian roses growing in the stony soil – and she told him to gather them carefully. When he returned with the roses, she placed them carefully inside a cloak she was holding. She then folded it and presented it to him, instructing him not to unfold his new cloak until he stood before the Bishop.

La Casa Colorada – Pedro de Urdemales at Malinche’s House

Don Pedro de Urdemales was first introduced to Doña Marina in the great house in Coyoacán some days earlier. She seemed tired and irritable at first, whisking him off to a quiet room near the back where a canvas was spread on an easel. She needed to produce a miracle, she said, and she had hired him for his skills as a painter. Matienzo, Delgadillo, Nuno de Guzmán and the others were out of control. Even Cortés’ return the previous year had not restrained them and the dream she and Cortés shared was dying as the country slipped toward civil war. The overlords’ greed had resulted in thousands of Nahuas being sold into slavery, torture and death for those who resisted, sexual violence against local girls and excessive taxation for those who put up with it all. Bishop Zumárraga appeared unwilling to stop them. To make matters worse, an angel of death was stalking the land, carrying away thousands more every year with pox and pestilence. This was not what Doña Marina had in mind during the initial Conquest and why now she thought a miracle was required.

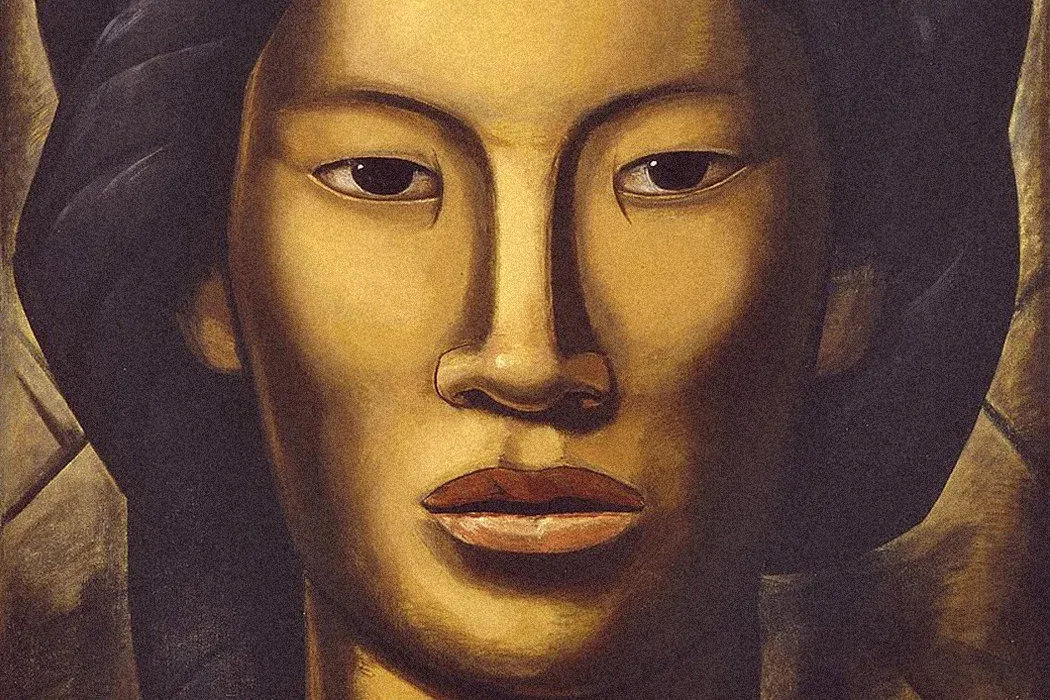

Don Pedro was to paint her as the Madonna, she insisted. He had agreed to this because he fancied his skills as a painter. He specialized in madonnas, having seen many of the works of the masters in Italy. Indeed he thought he could improve on Sandro Botticelli’s and Raffaello Sanzio’s “The Crowning of the Virgin” and Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Virgin of the Rocks,” all of them far too cluttered, he thought. He favored the clarity of a single figure in the center of the canvas. He recalled the portrait of the Florentine woman who had stared back at him in da Vinci’s studio: the Holy Mother would not stare back but there was something in the look he wanted to capture. Pedro thought to himself, “I will paint her in my imagination as I desire her…And let the world think what it wants.” Doña Marina had brought him up short by reminding him that it was essential that he Europeanize her face, for the Bishop would never accept a painting of our Lady of Guadalupe if she looked like an Indian. The cactus hemp parchment itself was brown, and that alone would convey the coded message that this Virgin was a Nahua, La Virgen Morenita. That appealed to Pedro’s sense of humor, of course. He would do as she asked, but in the end he felt it was the sun’s rays around the edges that would truly make this his masterpiece, his signature work.

He wondered if Cortés himself was behind this stunt. Was he somewhere else in the house? Doña Marina was a distinguished looking woman, even attractive in her own way. She was clearly accustomed to authority, but she was a native after all. Could she have come up with such a clever stratagem on her own? It occurred to Pedro that Cortés was from Extremadura and the original Guadalupe shrine was in Cáceres. If Columbus, Cortes and the Franciscans who went with them worshipped there before sailing westwards, then it would make sense if the idea had occurred to Cortés, not to Doña Marina. But they had been together on and off for many years so perhaps she knew more about Spain than he realized.

While he painted her, she told him the secret Nahua codes. She told him that the sky blue greenmantle with the stars emblazoned upon it would symbolize that she was from an Aztec royal family and that she had great power in this world. But her hands were to be folded in prayer in keeping with European traditions and her head would be bowed in reverence to the God of all things. Her pale dress was the color of the brown earth of México, stained by the dried blood of its people sacrificed during its creation. It was, she said, the story of life through death, of new beginnings, of resurrection. The black maternity band high around her waist meant she was carrying the Christ child, a child of the New World, the first mestizo, like Martin, her son by Cortés, born eight years ago. The crescent moon she stood upon symbolized Tonantzin, the Aztec earth mother and moon goddess, but the angel supporting her would provide proof that she was carried here from Heaven.

The painting went quickly, feverishly applied and it was finished by the early morning hours. Exhausted but satisfied, they both retired for the night. In the morning as they surveyed the previous night’s work, Doña Marina laid out her plan to create a new pilgrimage site around this painting. The original plan she had had was very simple: she hoped to encounter one of the naïve villagers who attended the Spanish church on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, December 8. But it had rained that day and no dupe had come along… The next day Juan Diego had appeared and he was perfect! She had revealed herself and her wishes for a new church to be built.

The problem was Bishop Zumárraga. After the second visit, he had ordered several trusted aides to follow Juan Diego secretly, but they had lost him at a ravine by the hill. Doña Marina also had spotted the spies and she reasoned she only had one more opportunity to impress Juan Diego and snare the skeptical Bishop.

That was where Pedro came in. He was to track the villager’s movements and waylay him on the path over Tepeyac to ensure he crossed again at the critical spot where Doña Marina could intercept him and make her final appearance. This is indeed how it played out.

Pedro had listened to this extraordinary assignment back at the Casa Colorada. He had heard Doña Marina speak of the magical power and strength of women and how she favored the Virgin Mary over Jesus Christ because she was a woman, a lover and a mother. All along it had appealed to her sense of irony that the great Aztec empire would be brought down by a woman – herself of course – but also by her ancestors, by Tonantzin, just as the great Spanish empire had been humbled by the Virgin Mary, the Spaniards’ Achilles heel, for they could not resist her power upon them. Of this much she was sure and Cortés knew it too. She had seen him take down the Aztec gods and put up the Holy Virgin and seen the power it exercised over the conquistadors. Jesus Christ on the other hand seemed to have no appeal at all, and if her own people associated him with Quetzalcoatl, then the general consensus was that he was an alien invader returned from the sea to upset the apple cart. The old gods were dead but the old goddesses were back, in all their jangly and jealous rages. As he listened, Pedro kept his opinions to himself; he was being well paid to do so.

Flash forward many years, back to Old Spain, and Pedro was present one day as the firebrand clergyman Father Bartolomé de Las Casas confronted an aging Cortés about the events surrounding the miracle of Guadalupe, asking whether he felt badly about his role as a conquistador and whether he was behind the whole Virgin thing. Cortés brushed it aside of course, but Pedro thought back to those days back in 1531, remembering his visit to La Casa Colorada. As he had excused himself that last time, the shadow of the great man could be seen down the hallway. That was how Cortés would be remembered, he thought, as a flickering shadow on the wall, no more tangible than that, just another symbol of the insignificance of human actions in the greater scheme of things. Hopefully his painting of Doña Marina would last longer than the memory of Cortés…

La Casa Blanca - Bernardino de Sahagún in Tlatelolco

In the candlelight, Friar Bernardino de Sahagún sat staring out the window as shadows danced like devils on the trees outside. Even here so far from Spain the presence of the Inquisition made itself felt. It was 1536, Tlatelolco Mexico, in the newly established Imperial College of Santa Cruz for the academic and religious training of native youths. Sahagún was proud to be one of its first teachers.

The conventional wisdom among the Spanish here was that the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe was a complete fiction. But what could they do? The Indians were acting as if it was a miracle and flocking to convert to Christianity. Should the Church capitalize on this misunderstanding or was that dishonest? The Inquisition certainly wouldn’t approve. The appearance of Our Lady of Guadalupe had been to an Indian no less. It was like Jesus appearing to Mary Magdalene after the Resurrection rather than to Saint Peter. What of his own role? Was he a dupe of the Indians in this matter? Were they all dupes?

The crucial moment had occurred some years earlier: “Peter denied knowing our Lord three times and you have denied the existence of this miracle twice already. Will you do so a third time?” With these words the dubious character he knew as Don Pedro de Urdemales had challenged Bishop Zumárraga. The Bishop rightly had refused to be baited but Pedro had kept up the pressure and the Church had been forced to concede the miracle, for like it or not, they had been outmaneuvered. If they wanted converts, they had to build the small church to Guadalupe on Tepeyac, which the miracle called for, and this they had done, in 1533. Now the natives were flocking to it in such numbers that an expansion was being considered. But things were not what they seemed to be. Sahagún had never felt so unsure of himself. Were the natives pretending to be Christians? Was Satan playing a capricious role in all this? Sahagún knew he was smart but was he as smart as Satan, smart enough to figure this out as a ruse? Smart enough to thwart it?

Bishop Zumárraga was gone now, back to Spain, and he had strongly opposed relying on apparitions and miracles to convert the natives. He had believed instead, as any man of intellect would, in the superiority of this College, which would prepare the way for an Indian clergy. But the Guadalupe cult was taking on a life of its own, quite apart from the College. Somebody, and he had no idea who, had been very clever to identify the apparition on Tepeyac with Our Lady of Guadalupe. How had they known to do that? The scheme was so diabolically clever that he felt sure it had been thought through to its completion. The fact that the apparition of the Virgin Mary was to a native man and a simple one at that had made it so much easier for the miracle to be accepted everywhere. He had gone around in circles many times thinking about it.

Sahagún had recommended a new strategy to counter the native Guadalupe, as if she were the Devil himself, and he had received official approval. He would later write of this moment: “It was necessary to destroy the idolatrous things, and all the idolatrous buildings, and even the customs of the republic that were intertwined with idolatrous rites and accompanied by idolatrous ceremonies…” The way to do this was to say that it had all been a misunderstanding: Juan Diego had in fact said the apparition was of “Coatlaxopeuh,” not Guadalupe. Because it was pronounced “quatlasupe,” this had been misunderstood as “Guadalupe.” That was wrong. As a pagan apparition, it had to be stamped out. The Inquisition was very clear about this. In April of 1531, it had been behind a decree banning historical romances and picaresque tales (like Amadís de Gaula) from being brought from Spain to Mexico, in case their profanities and leaps of imagination encouraged the natives and local Creoles to engage in fanciful thinking for themselves. But the decree had not worked for here he was now, embroiled in just such idolatry.

There had been complications as well… Perhaps not at first. Everyone had agreed that Coatlaxopeuh was translated as “crushing the serpent,” which confirmed for them how Cortés had crushed Quetzalcoatl, the Aztecs’ plumed serpent god. It also recalled how God could crush Eve’s serpent. But Pedro de Urdemales had pointed out that the white-bearded Cortés had also been associated with Quetzalcoatl. So did that mean that Cortés was the one being crushed? Everyone had laughed at the joke for it was true that Cortés was now a man of the past. But who had crushed him? Who, Pedro asked, if not the Virgin of Guadalupe? Sahagún’s head began to spin all over again. He should have realized the natives would misunderstand, but he hadn’t counted on Pedro de Urdemales. No doubt the natives were secretly praying to their old mother goddesses of the moon, Tonantzin and Coatlicue, not the Virgin. What a mess! The Inquisition was asking more and more questions -- about the painting, about Pedro de Urdemales, about native traditions – and he was supposed to come up with a solution? There was none to be found.

La Casa Azul – Frida Kahlo as Guadalupe

The house known as La Casa Azul is on the corner of Allende and Londres Streets in Coyoacán (“Place of the Coyotes” in Nahuatl), in the southern suburbs of Mexico City. It was built by Frida Kahlo’s father in 1904 and it is a museum to her work, much visited nowadays by tourists. It also can be seen in her painting of 1936, “My Grandparents, My Parents and I.”

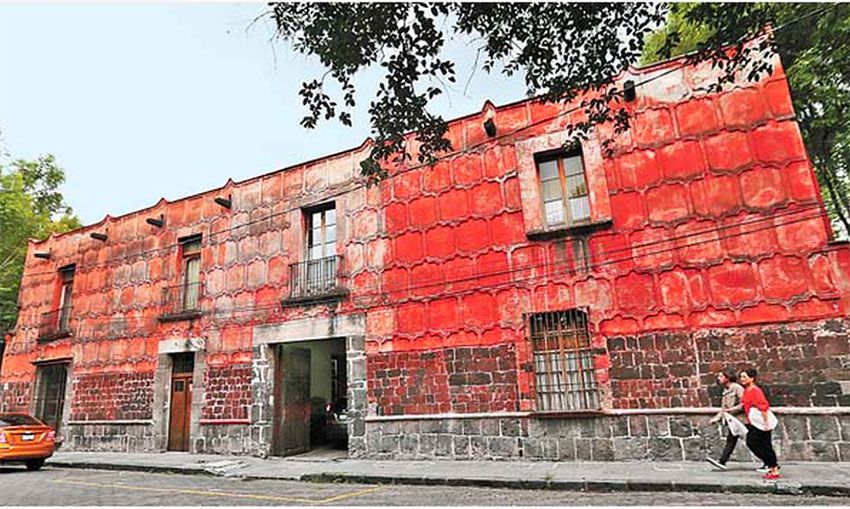

It is a short walk from there to 57 Higuera Street, Malinche’s house, nicknamed La Casa Roja. But there is no sign to tell you Malinche and Cortés once lived there – this is one tourist attraction that Mexico is not proud of. The house has been restored and remodeled several times since the 1520’s, but it has suffered earthquake damage and it needs a proper restoration. Many locals believe some ghosts are better left undisturbed, of course, and Malinche’s ghost is still strong here.

The ghost of Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderon de Rivera hovers here too – and it is stronger than at La Casa Azul which, like all museums, is barren of ghosts! Outside the house there is a bronze statue of Kahlo and there are family associations that go way back. Jose Vasconcelos, that fascinating Mexican philosopher and educator, bought the house in the ‘30s while he was in exile and he rented it out to (among others) Lupe Rivera Marin, Diego Rivera’s daughter. Until recently, the house was lived in by the late painter Rina Lazo who was Rivera’s assistant for 10 years and her husband, Arturo Garcia Bustos, who was a member of the illustrious “Los Fridos,” Kahlo’s disciples.

Kahlo’s ghost still excites the same extremes of emotion today that Malinche’s ghost once did, just as Rivera’s Rockefeller Building mural did in its day… Those emotions reconverged with the release of the movie by Salma Hayek and Julie Taymor in 2002 as some reviewers rushed to condemn the film for not sufficiently emphasizing Kahlo’s pain, which only goes to prove that Anglo critics too believe in La Llorona. That’s the current dogma in art circles too – stigmatize Frida as penitente sect member, as La Doña Sebastiana, crucified by her early collision with the street-car – the paintings of grief and sorrow, like The Two Fridas (shown below). Art critics and film critics join Mexican critics in denouncing Kahlo as a “crippled bisexual Communist” or a “Stalinist feminist heroine,” where the sneering is surprisingly nasty. They are as tone deaf as the ideologies they accuse her of. They rob her of her active resentment and fierce creativity and they render her into a passive victim, as if she were imprisoned inside one of her paintings.

No doubt this is partly to compensate for the idolizing of her fans, for Kahlo has so many! But it is Kahlo’s support for Communism and Stalin that inspires the harshest barbs. Ideologies promoting revolutionary struggle have long seduced Latin American artists and intellectuals, but Latin American realities almost have demanded this response as an ethical alternative to the abuses of power by the Right. Kahlo, like Rivera to a lesser degree, was an idealist and a Mexican nationalist before she was a Communist. She saw the inequities in society, both at home and abroad. Indeed her last public appearance with Rivera was at a demonstration protesting the C.I.A.’s ouster of Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán.

Kahlo and Rivera also saw the hypocrisies and self-indulgences of the Party, which is why they were kicked out -- they were simply terrible Party members. Like all great artists – and this is especially true of Kahlo -- it was always more personal than that and her paintings say so. She used Communism (and paintings of Stalin) for tweaking the noses of the rich just as she wore her tehuana costumes to startle their eyes. Did she know inside that Stalin and the Party had as much blood on their hands as the Capitalists and the Fascists? There was no doubt some denial going on, especially after Stalin brought personal destruction down upon them with the assassination of Trotsky. But after Kahlo’s death in 1954 and Rivera’s in 1957, the right wing forces in Mexico proved they could be as brutal as Stalin, reaching their historic low at Tlatelolco in 1968.

Back at La Casa Azul, Kahlo was also very much aware of The Most Holy Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Guadalupe, Queen of Mexico and Empress of the Americas. Not in a conventional religious sense of course for, like Rivera, Kahlo did not believe particularly in a Catholic God. But she drew on the religious iconography of the country and she respected Guadalupe’s revolutionary importance, her standing for the oppressed, her symbolizing hope and unity. In her own struggle for integration and harmony, the country’s preeminent symbol of virginity and purity had a powerful appeal for her.

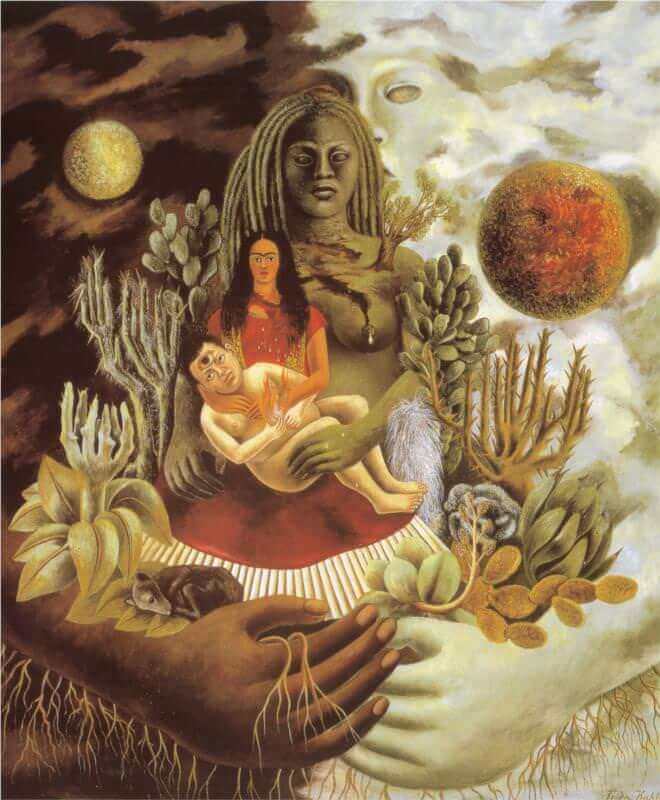

The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Diego, Me and Senor Xolotl (above) which Kahlo painted in 1949 is her finest painting in my opinion. A beautiful and haunting Madonna image, it shows her in the love embrace of an earth mother whom observers usually identify with Coatlicue or Tonantzin (“Mexico”), protecting and nourishing her, held within the wider embrace of the universe. I have always been tempted to view the central figure holding Frida as Malinche and the masked androgynous figure in the background as Coatlicue or Tonantzin. Frida is holding a baby Diego Rivera, but for all his all-seeing eye, Frida is the center – this is the center of the universe as she sees it, as indeed we are all at its center, wherever we are, and she is humbled by this, just like the pregnant Guadalupe is humble in her painting. Compare this with the cocky Quetzalcoatl, with D.H. Lawrence and his plumed serpent and with the pessimism of Paz and Fuentes. There is no Quetzalcoatl here, no male deities in transcendence or falling to the earth. This is a painting of female power and coming to terms with life and motherhood: Frida/Malinche/Tonantzin is the earth and the moon, fertility and childbirth, the cycle of birth to death and Diego is her child. This painting unifies the conflicts of her life, it celebrates oneness with the universe, the idea that the dueling pieces are really in synch by being part of the same whole. It is Frida as Guadalupe.