La Malinche and Hernán Cortés

For many in México today, Malinche is someone they have never heard of. For those who have, she is a symbol of anyone willing to sell out their country to the gringos. As Cortés’ translator, she was nicknamed la Lengua, “the tongue” for her diplomatic skills and, with Cortés, she was an essential reason why the Conquest succeeded when it should have failed. The Spanish knew her more respectfully as Doña Marina and the theory goes that Nahuatl speakers replaced the Spanish r with an l and added -tzin, a term of respect, so Marina became Malintzin. Because the Spaniards had difficulty pronouncing the Nahuatl –tz, they in turn changed it to –ch, and they dropped the silent n at the end of her name, so in a roundabout way she became known as La Malinche. With its prefix mal-, the name retains negative connotations in Spanish. One testament to her success though: Cortés was often called El Malinche after her.

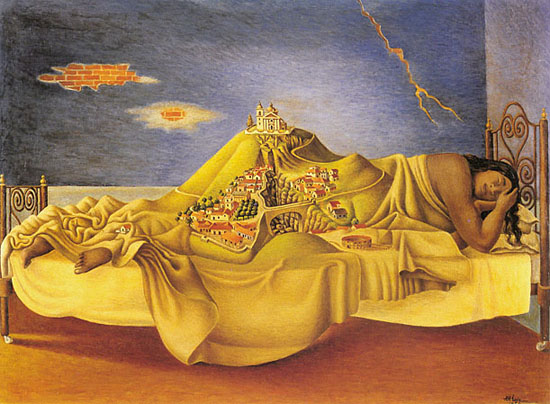

Below is a more symbolic interpretation of Malinche, El Sueño de la Malinche (The Dream of Malinche) by Mexican painter Antonio Ruiz in 1939.

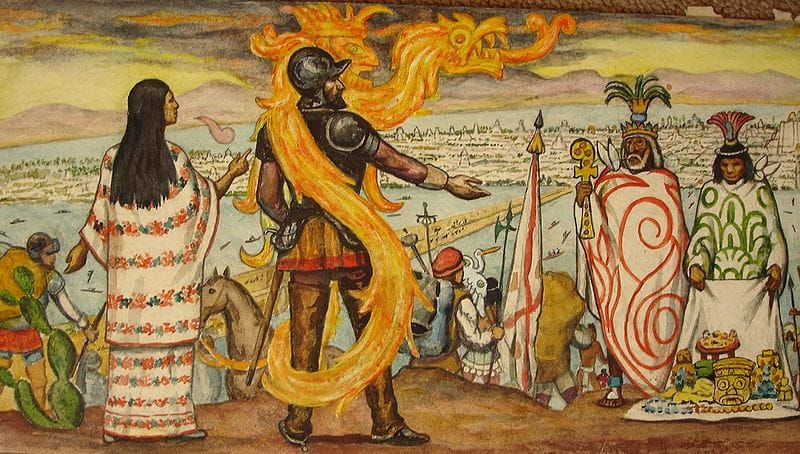

Cortés of course fared no better – he is still mostly “damnation memoriae” (damned in memory, meaning he’s never talked about either) in México. He does appear with Malinche in a mural by Diego Rivera and in another by Clemente Orozco. The latter is more directly symbolic of the nation’s primal scene, which would produce the first mestizo, Don Martin Cortés, their son. The meaning of Orozco’s mural is much debated, but it is doubtful if it can be viewed as a positive image.

Back in the 17th and 18th centuries, a whole genre of paintings arose to portray the mestizaje, or "mixed-race" people of New Spain. Called "casta," these paintings are best represented by what we would now call Méxican artists, such as Miguel Cabrera, who was most active in the 1750's and 1760's. This is one of his most interesting paintings, although it's not an example of casta.