Agatha Christie and Modernism

The heyday of Agatha Christie occurred at the same time as the triumph of Modernism, which is surely no coincidence. Do they in fact have an affinity with each other or are they opposites? It's a trite question but often asked. Christie was as comfortable blowing up pre- and post-World War I artistic conventions as anybody else. The difference is that she allowed the reader to participate, which is why she was read and they weren't.

Nowhere is Christie more "modernist" than in The Mysterious Mr. Quin, a collection of short stories first published in 1930. Even though its mysteries are resolved, they leave the same sense of unease as other modernist works, where it's apparent that both tradition and modernity are mirages. She just draws attention to the literary machinery in a different way from, say, the Bloomsbury Group or the Surrealists. In celebrating Commedia dell'arte and its dark whimsy, Christie isn't that distant from Picasso, Stravinsky and Chaplin and writers like P.G. Wodehouse and Georges Simenon.

"To Harlequin the invisible"

While Christie enjoyed the process, it drove French poet Paul Valéry up the wall.

(Valéry) could never write a novel because sooner or later he would find himself setting down such a sentence as "The marquise went out at five o'clock." Why did the marquise leave at five? he wondered. Why not at six or seven? In fact, why did she go out at all? And why a "marquise"? Why not a duchess or a washerwoman? The arbitrary nature of narrative devices irked Valéry; they pretended to an authority that was, at bottom, a sham.

That great Valéry line can be sourced to André Breton in Manifeste du surréalisme in 1924 and the paragraph itself belongs to writer Eric Ormsby who puts it exquisitely, in the Wall Street Journal no less.

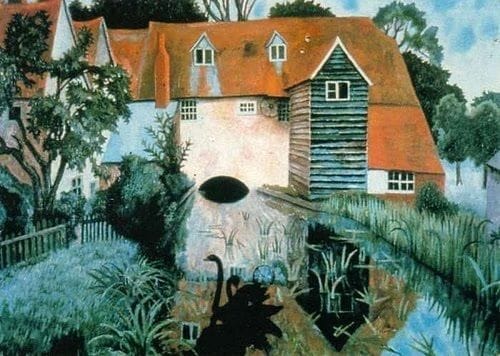

Another who struggled with this dilemma was the under-rated painter Dora Carrington, arguably the most interesting figure associated with the Bloomsbury Group. She was almost an antithesis to Christie and when her life unraveled she committed suicide in 1932. Above is her celebrated painting Tidmarsh (1918), a mill house near Reading that was one of the Bloomsbury Group's favorite retreats in the years after World War I, just as Greenway would be for Christie.