Angel Incarnate

Leonardo da Vinci and the Pleasure of Boys

Leonardo da Vinci and the Pleasure of Boys

Once upon a time, a small drawing by Leonardo da Vinci went missing from Windsor Castle’s art collection. It is known today as Angel Incarnate (Angelo Incarnato), and it shows his young assistant Giacomo Salai with a prominent erection, no angel wings and a sweet come-on invitation. The drawing magically reappeared in 1990 and scandalized art critics, but no one else noticed because the media helpfully cropped the drawing above the waist. Below is what all the fuss was about. Notice that his erection has been disfigured by some high-minded individual.

There is little doubt Leonardo drew it since his handwriting is on the back. Until then, the private life of Leonardo had been considered – well – private. What we thought of Mona Lisa or The Last Supper had nothing to do with his sexuality, so it was said. As far as art critics were concerned it was off limits to discuss what we do (or what he did) in the bedroom and when the general public trouped along to the Louvre, they were, and are, blissfully unaware that Leonardo was gay or, for that matter, that many of the great Renaissance Italian artists were.

Freud got there first, of course, back in 1910, when he published Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood, in which he argued that Leonardo’s "homosexuality" was revealed in his life story and in his art, chalking it up to his being raised by a solo mother. Freud was unaware of Angel Incarnate but his instincts were impeccable, even if he was wrong about Leonardo's instincts ("the affectionate relationships of Leonardo to the young men did not result in sexual activity. Nor should one attribute to him a high measure of sexual activity," he wrote). Outside academic circles, however, no one noticed this until distinguished art historian Kenneth Clark referred to it in 1939 as “the kind honoured in classical times, and partly tolerated in the Renaissance, in spite of the censure of the Church.” This was provocative for 1939 but again, on the whole, it did not attract attention since it was so oblique and anyway war was coming. Restraint was called for. Not because this was a genius we were talking about and geniuses could not be gay, but because talking about it might bestow some legitimacy when homosexuality was supposed to be all about guilt.

All this is well known to art historians and academics. I rehash it here because of their reactions to Angel Incarnate, which they have described, almost unanimously, as “ugly.” Why are they so repelled? Why is it ugly? Nearly as many say similar things about St. John the Baptist (shown at top), which also is in the Louvre.

Let me ask it another way: if Leonardo was sleeping with Salai before the boy turned 15, why the restraint in discussing that? Is it because in today’s academia and in the media, the notion that there might be absolutely nothing wrong with a man in his 40’s sleeping with a 15-year-old (or younger) beautiful boy just isn’t discussed? If it is discussed, it is in censorious terms (pedophile, pederast, pervert – there’s a monopoly beginning with “p”?), such that all room for debate is crowded out of the bed. Why is this? Have we reached the point where moral judgments about homosexual behavior - sodomy in particular - can conceive of no empathy for Leonardo, no act of imagination that could allow for the possibility that this love, this sex, is just as blameless as being left-handed? And if you are fine with it in late 15th century Italy, why not in the present-day in your own neighborhood where sodomy is a popular heterosexual activity and where gay rights are majority-supported, but where gay sex is, well, not.

Savonarola and The Pointing Finger

Leonardo da Vinci's contemporary, Fra Girolamo Savonarola, understood the meaning of these drawings clearly. He could see in them the same lurid invitation that you would see in the brothels of Rome or Florence: a perverse and profane mockery of religious icons and a revelation of the secret beliefs of Leonardo about St. John and the Savior.

"The Angel Incarnate is an unsavory-looking catamite fished up from the lower reaches of the Roman flesh-market." This “angelic” being resembles transsexual pornography, for in this blurring of the sexes there is something almost satanic, something demoniacal and diabolical. The pointing finger mimics the gestures of the brothel while at the same time declaring that it points toward the divine. That is heresy.

Leonardo’s defenders have made the case naively that Angel Incarnate is sweet and affectionate, a display of eroticism and desire, especially that feminine nipple, and they ask why shouldn’t that sweetness apply equally to homosexual relationships, no matter the age of the partners. Al contrario, Fra Girolamo correctly has rejected this: “the Signoria must make a law against that cursed vice of sodomy, for which Florence is defamed throughout all of Italy... Perhaps you have this disgraceful reputation because you talk and chatter so much about this vice; maybe it's not so widespead in fact as it's said. I say, make a law that is without mercy, that such persons be stoned and burned.”

Fra Girolamo Savonarola’s young religious boys were the tip of the spear. They cut their hair short and wore modest clothing and they went after the rich and corrupt young men of Florence for their activities of the damned. Also, prostitutes were brought into the city to encourage men to forgo sodomy. Which is not to say that only men participate in sodomy. Heterosexual couples also were charged and some of those prostitutes flogged and if other places of ill repute like taverns were inadvertently trashed, then let it be said that the Officers of the Night had the full support of all artisans and merchants. The highest goal was to save Florence the holy city, the Jerusalem of Europe, the center of a glorious religious awakening from the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah.

Leonardo and three other young men were accused and charged, back in 1476, with committing sodomy with one of the models, a prostitute named Jacopo Saltarelli. In those days, while it was true that anyone could make anonymous allegations to eliminate a rival, the charges likely were well-founded. They were dropped in the end and Leonardo remained extremely secretive about his private life thereafter.

Homosexuality and homosexual sex are repulsive, not just in and of themselves, but because they do not lead to marriage and procreation. Masturbation is self-abuse, and this in turn corrupts society and weakens the family. “Do you wish to be free? Then above all things, love God, love your neighbor, love one another, love the common weal; then you will have true liberty.” But do not love them carnally, for this is selfishness, this is vanity and it deserves to burn in the fires of hell.

And so the bonfires of the vanities became inevitable and necessary. Wisely Leonardo kept away from Florence between 1495 and 1497. Raising up young boys like Salai from the gutters is but a cover for the vile practice associated with those Florentine men who are attracted to young boys. Artists must use their gifts to illustrate the Bible so as to educate those who are unable to read, not to engage in base physical vices.

Michelangelo and the Fires of Platonic Love

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni and Leonardo da Vinci both experienced platonic love first hand. Everybody did - Erasmus, Machiavelli, Botticelli. For modern cynics, platonic love is just another name for homosexual love. They point out that theories of platonic love arose in classical Greece and Renaissance Florence, where sodomy was popular. Indeed it was in 15th century Florence that humanist philosopher Marsilio Ficino first coined the term.

The truth is something different though. At this time in Florence, one could say that although sodomy undoubtedly occurred, it was not homosexuality per se, since the term did not exist, but platonic love, and that platonic love allowed for eros occasionally. "Relations with men were more likely and more frequent," writes Michelangelo biographer William Wallace. This did not always mean sodomy. It also did not rule out marriage to women, although women were uninteresting, and neither Michelangelo nor Leonardo ever married. Ficino is the figure on the left in this painting:

The goal of platonic love, whatever orgasms were occurring, was always to redirect attention away to higher spiritual things. A beautiful and lovely boy like Tommaso dei Cavalieri could inspire the mind and the soul like Dante's Beatrice. It was St. Jerome who had said: "The face is the mirror of the mind." He meant that external beauty reflects the beauty of the soul. This bold idea caused confusion and doubt, of course, for was such desire unholy? Yet, if God had created such male beauty, then it had to be divine, no? Ficino concluded that this platonic love was timeless and not physical at all and this produced great relief. Platonic love had to be more than a mere physical release, more than a mechanical transaction. Just as sex passes quickly, so too does sodomy fade with time as chastity and abstinence become more important as we age and the aches and pains and the longing set in. This is how Michelangelo retained his clarity of vision throughout his life. He lived the experience of the pilgrim soul alienated from God and the light who seeks eventual reunification with the Creator and forgiveness for his sins. It sustained him - he lived to be almost 90.

There is an analogy here between spirituality and art. For Michelangelo, as in Dante's Inferno, sculpture expressed the extremely physical, even violent struggle of the soul to be liberated, to escape its material bounds in order to return to the infinite, just as we must escape the torments of the flesh - those naked boys in Doni Tondo or the Sistine Chapel ignudi. Art demands that the artist draw out the ideal form that exists within every virgin piece of marble, or the fresco from the blank space and this should challenge the viewer just as God challenges us. There is nothing mundane or pious in the virile art of Michelangelo. It was very much a performance delivered with his face, his eyes, his gestures and language, his sculptures, his frescoes, terrifying his employers and even a few popes. His intensity and defiance were the complete opposite of Leonardo.

Leonardo, unfortunately, was a working class dandy in colorful doublets and tights, a long-haired and unshaven producer of unheroic sexless art. Children born in lust never amount to much and he was fundamentally unserious in his approach to art and life. "He owned, one might say, nothing and he worked very little, yet he always kept servants as well as horses," wrote Vasari. With Leonardo there was too much focus on individual vanity rather than a deeper religious spirituality that might have pulled him towards God. With him, things were always in a state of flux, expressing Nature's impermanence perhaps, water running through landscapes "without lines or borders," sfumato, smoke and filtered light. His defenders talk about immanence, where a divine light shines from within. They talk about humility and femininity, but there is no transcendence here, no salvation.

Most artists aspired to move out of the artisan class and into the elites, where some became celebrities. Michelangelo and Leonardo, notably, chose different routes to get there: the heroic Prometheus or Hercules or Bacchus, sweaty and dirty and seeking his own divinity, a survivor whose paintings and statues are revered today. Then the other: the secretive anti-heroic magician and scientist undermining it all, his very paint peeling pathetically off the walls in Santa Maria delle Grazie, his other paintings unfinished.

François Rabelais and the Mirror of Time

If you wish to avoid seeing a fool you must first break your looking glass, said Rabelais. Good advice, or you will simply find what you went looking for.

By the late Renaissance, Plato's notion that mirrors are metaphors (for the way art reflects life) was in trouble. The use of Trompe l'œil - trick of the eye - would indicate it was being parodied by the time Leonardo was writing backwards in his journals and presenting Virgin of the Rocks and The Last Supper to appreciative audiences.

There were some in positions of power who missed the point, just as they do today. They "do not see themselves in the mirror of time," writes Mikhail Bakhtin (in his book on Rabelais). He does not elaborate on what this means but I assume he means that those in power are unable to see themselves as living within a history or a story or a painting (the mirrors of time). "Time has transformed old truth and authority into a Mardi Gras dummy, a comic monster that the laughing crowd rends to pieces in the marketplace," writes Bakhtin. In exile in Soviet Russia he too saw the king behind the abused and the beaten. Artists and musicians and storytellers tend to understand this best. They see the old order eroding around them just as they know they are eroding too.

Rabelais was popular with the carnival crowd and unpopular with the elites who relied on truth and authority. This suggests the hoi polloi intuitively understood satire and the possible meaninglessness of all things and they appreciated the performance. This did not protect Rabelais and he was forced to move around a lot. In the same way Leonardo spent years carefully avoiding scrutiny of his private life, which resembled a commedia dell'arte ensemble traveling from town to town. His colorful "family" - Salaino, Melzi, Zoroastro, Boltraffio - they could have strolled onstage from Rabelais' La vie de Gargantua et de Pantagruel. Charlatans and tricksters all, they were centered around Leonardo, who had a propensity for jokes, games, puns and puzzles. La Gioconda means "Joking woman" after all. But Leonardo elevated the performance. He was no stock character, he was the producer, puppet-maker, costume designer, lute-player and storyteller.

Like Rabelais, he understood the follies of those in power and the lure of the forbidden, but unlike Rabelais he was interested in irony, not satire. He preferred a limpid mirror held up to life, a pittura è una cosa mentale shaped by a life's memories. In his great paintings, Time hides in the details - in the smile, the eyes, the fold of the hands or the clothes. Those details focus the gaze so that the rest of the world (the painting around it, the room, the gallery, the city) recedes temporarily and perhaps - if we are lucky - we see the mirror of time. It is easier to see with age but more often than not it is a serendipitous thing found in life's quieter moments, not in an art gallery. Now Leonardo's paintings are on display for Rabelais' carnival crowd and several times they have tried to steal or mutilate Mona Lisa because now she too is truth and authority and so they must stand twenty feet back.

When Leonardo's paintings were viewed in their own time, they were viewed up close. His greatest paintings refuse to just sit there; they move like his models must have done and they return the gaze, which is why there has been so much speculation about Mona Lisa and why there is so much confusion over St. John the Baptist and Angel Incarnate. The paintings either look back directly or they express an inner contentment and private peace as Saint Anne does or they catch the vanishing point into infinity the way The Last Supper does. In none of these cases is there any attempt to forcibly impress a viewpoint on the viewer. They are performances but they are invitational, not confrontational as in Rabelais. They express our shared divinity, which is a birthright, not something to be earned or bought. It was this generosity that made Leonardo famous in his own time.

Michelangelo disdained it as too soft, too feminine. If Michelangelo's women look like men then Leonardo's men look like women. Leonardo, of course, while sexually attracted to boys, remained fascinated more by the spiritual qualities of creation. This meant not just women and motherhood, but the movement and flux of life, the way the human body's architecture resembled plants, trees and rivers, the way the flow of hair resembled water, grasses and rushes, which is why he could buy captive birds their freedom and espouse vegetarianism. Many of his most admired paintings are of women - the inner smile of the Sphinx - but he poses exactly the same question in St. John the Baptist and Angel Incarnate. All these paintings ask: do we reveal something to you of the mirror of Time or do we make of it a mystery that you do not understand? Science or alchemy?

Despite all this, Leonardo had no particular interest in leaving a monument for the ages. Why else would he have continued to use unstable painting materials for The Last Supper fresco? Why else would he have left so many things incomplete? Why else did he hold on to his best paintings until his death - The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist? Because he knew that all things perish and if he let them go now, then they would perish quicker or, conversely, if they were never completed, nor was he? Leonardo thought these paintings were his best works and on his death these paintings were left to his assistants who, in the end, were the people who mattered to him the most.

Machiavelli and the Divine Madness of Love

Niccolò Machiavelli married Marietta Corsini in 1501 or 1502 and the marriage appears to have been a happy one. A few letters survive (although none are from him to her), and this was before anybody expected love out of a marriage. They had several children and although he had many affairs, there is no evidence of homosexual relationships although most of his friends indulged. Machiavelli was dead in 1527 at the age of 58; Marietta outlived him by another 27 years...

Do you value a husband who is loyal to you, gives you children, provides for you, and even if he has affairs and infatuations, you can overlook them because what is the alternative? A man who is faithful but who has no fire, no risk, no danger?

Although far better known for The Prince, Machiavelli is if anything more interesting in his comedies about love. In Mandragola (Mandrake) (1518) and Clizia (1525), conventional marriages are satirized and true love is celebrated. That has encouraged some modern critics to assume that Machiavelli was not satisfied within his own marriage and that he looked for love outside it. This prissy approach fails to see that Machiavelli may have been satisfied both with his marriage and his affairs. He was not satirizing marriage; he was satirizing bad marriages, especially conventional arranged marriages, and he was praising love as a divine madness that blew all that apart, driving characters to do things they might regret later, which is all right, since we all do it anyway if we are truly alive. Lust and greed, wit and trickery drove all the narratives of his day - Boccaccio, Chaucer, Rabelais - and they are inherently funny, not an occasion for the Inquisition. If today we call it infatuation and obsession, nothing has really changed other than the ways in which sex is moralized.

This is a world governed by Dame Fortune, which is another way of saying that in matters of love we are never in control. Not that Machiavelli believed in her any more than those other writers did - or more than classical writers did or Shakespeare and Ben Jonson did - she was useful mostly as a plot device and a metaphor. Machiavelli may have believed that fortune favored the bold (Virgil again), but that's only because the bold were the ones driving the plot. Leonardo seems to have shared that ironic view when he wrote: "When fortune comes, seize her firmly by the forelock, for, I tell you, she is bald at the back."

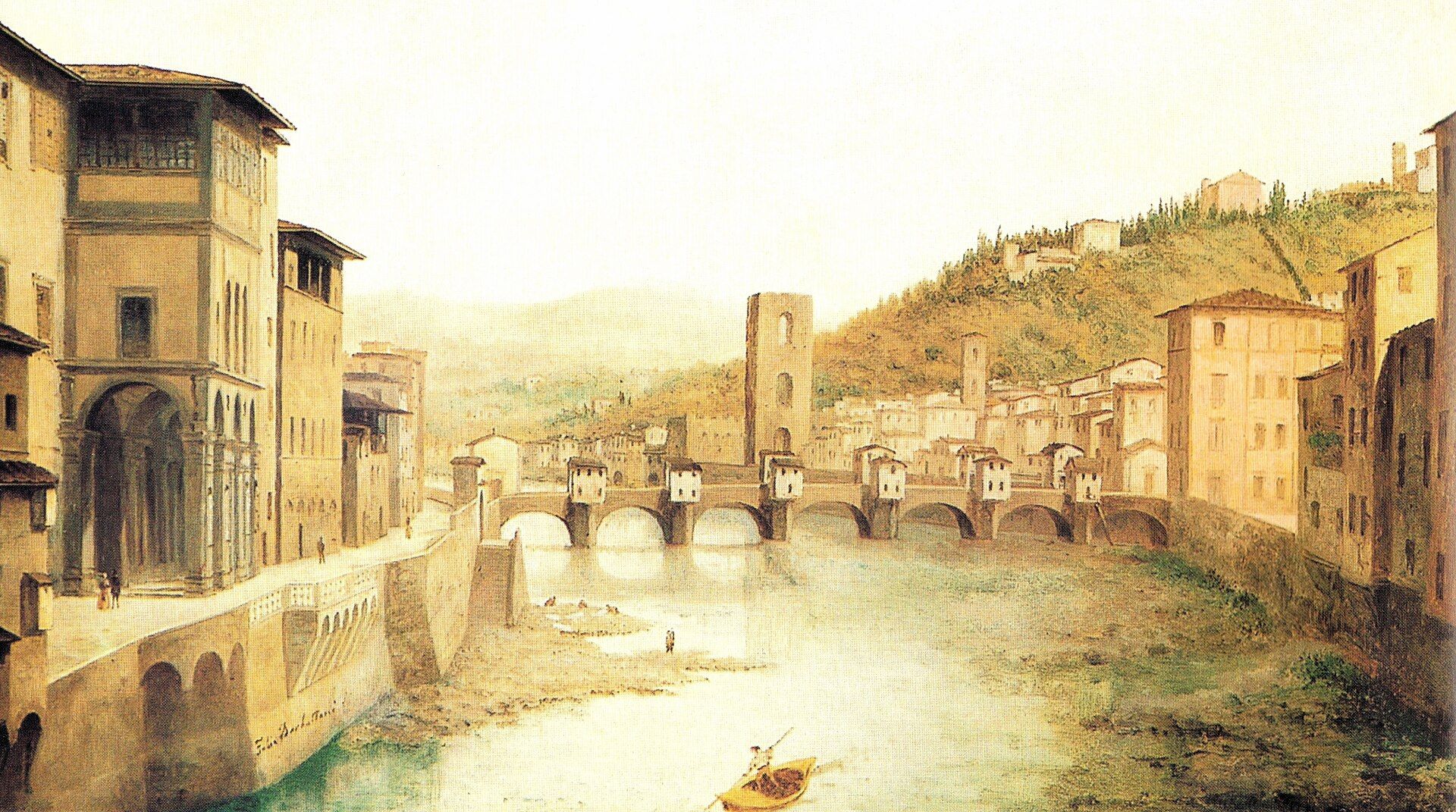

When it came to applying these principles to their private lives, Leonardo was far more cautious than Machiavelli, much more afraid of the deluge that could sweep them away like the Arno River they tried to dam. Leonardo was always aware that his homosexuality could attract the Inquisition, always hopeful his "lovable disposition" (Vasari) could help him avoid trouble. For Machiavelli these were political questions, not personal ones. Yet, as Leonardo's apocalyptic journal entries show, it was he who knew the deluge was always close by, and it was Machiavelli who would end up jailed and tortured (strappado), in 1512, not Leonardo.

Leonardo died in 1519 at the age of 67 in Amboise, France. "He died in exile: it was his lot, as it is the lot of all men, to live in bad times" (Borges). The Angel Incarnate, Giacomo Salai, survived him by only a few years. He was killed in a duel in Milan in 1525.