Boccaccio’s 'Decameron' - Day 3

Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron was written between 1348 and 1352 and it is large! A hundred stories told over 10 days by a group of young aristocrats (three men and seven women) who have fled Florence to avoid the Black Death. When some of today’s literary critics and academics say things like “probably the dirtiest great book in the Western canon,” they aren’t wrong, but it does tell you the Western canon needs more sex in it, certainly more sex without guilt.

If you are only going to read a selection of the best stories, try Day 3. My favorite is the 10th story (III:10), about Alibech and Rustico (shown up top). It was cut out of later Decameron editions for hundreds of years, or it was so altered that it was unrecognizable because, not only was it sexy and bawdy, it had the added virtue of mocking the clergy and their claims to abstinence, like many of the tales in Decameron. As a result, the whole book was regularly banned in Italy in the 1400’s and 1500’s, but circulated widely around Europe anyway, influencing Chaucer and Shakespeare, among others.

Day III:10 is the story of a 14-year-old Tunisian girl Alibech, who goes into the Egyptian desert to find a way to serve God. After being redirected by several holy men who would rather not be tempted by her beauty, she is referred to a young monk named Rustico who thinks he can beat the temptations of the flesh. He fails: he teaches her a way to serve God by putting the Devil back into Hell (i.e. his penis in her vagina). A lot of sex follows (“the resurrection of the flesh”) until she wears him out, but it all ends happily. And why not? Decameron is about many things, and Day 3 is all about sex without guilt.

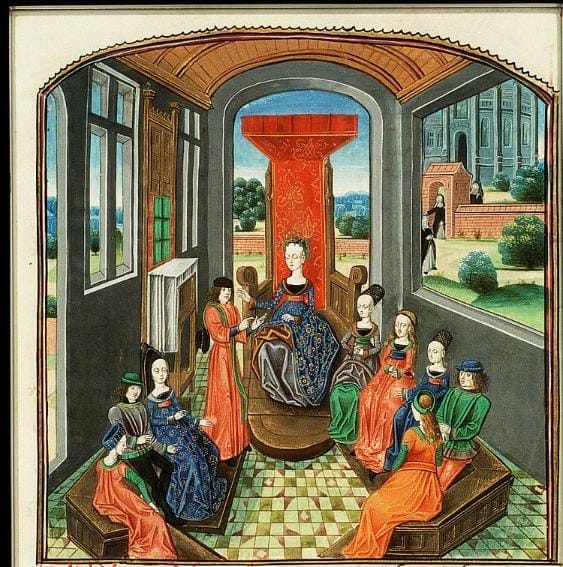

My other favorites on Day 3? In III:1, a young man pretends to be a deaf-mute to get a gardening job at a convent of 9 nuns. They soon start making use of him, including the abbess herself. In III:3 (shown above), a bored wife arranges an amazingly elaborate way to find a lover, using a naïve friar as the go-between. Lope de Vega, Molière and Thomas Middleton liked it too, enough to adapt it. III:4 and III:6 are similarly elaborate, but on those occasions it’s the man who arranges things. In all these stories, the lovers sustain their trysts over many years.

I would enjoy any book that is about romance and female infidelity, in the sense that such stories are usually about female empowerment. I also like VII: 2, about a quick-witted young woman named Peronella who has sex with her lover behind her husband’s back. And IX:6 (shown below), a comedy of errors (and sex), which was derived from the fabliau Gombert et les deus clers ("Gombert and the two clerks") by Jean Bodel (1200's) and which Chaucer adapted as The Reeve’s Tale.

Then there are the moralistic stories that other people seem to like, but which I find annoying, especially Day IV. Such stories include IV: 1, in which Tancredi executes his daughter Ghismonda’s lover, then sends her lover’s heart to her and she commits suicide. Another is IV: 5, about Lisabetta whose lover is murdered by her brothers and she plants his decapitated head in a pot of basil, which Keats adapted in Isabella, or the Pot of Basil. Then there is the most famous story of all, X: 10, about patient Griselda, which belongs to the ludicrous wife-testing genre. In fairness, the narrator of this particular story, Dioneo, is very critical of both his main characters.