Cherubs are the Fools of Renaissance art

Cherubs – or more accurately “putti” - in Renaissance painting and sculpture were, in my view, another variant of The Fool found elsewhere in the theater and literature of the time. They were a way of replacing classical angelic figures with more childlike and humorous characters that people could relate to, because they often - not always - seemed to be up to mischief. Some paintings, like Andrea Mantegna's frescoes in Mantua (above and below), dovetailed into illusionistic art, in keeping with the role of the Fool, who claimed that all is not what it seems.

After the seriousness of the medieval Gothic period when angels were often scary adults, or bizarre winged children, now it was fat naked babies with wings (Donatello and Raphael most famously), little boys peeing (e.g. Brussels’ Manneken Pis), and Cupid putti playing matchmaker (everybody else). Who are these weird kids? Are they just "helping out" or are they "playing the Fool"?

In academia and Wikipedia, a rather hilarious confusion reigns around distinctions between cherubs and cherubim, cupids, putti, spiritelli, imps and sprites, let alone angels. It's not a new debate: Guido Reni weighed in when he painted a fight between putti (the working class dark-skinned ones) and cupids (aristocratic lighter-skinned ones). You can see who's winning.

The Book of Ezekiel is no help in sorting things out: "Each cherubim had four faces: a man, a lion, an ox, and an eagle." The Greeks focused instead on Eros, the god of love and sex. Romans and Byzantines repainted him as Cupid and later called him an angel. Perhaps putti angels in explicitly religious art were a symbol of divine love and the innocence of children, but without the sex associated with Eros. In secular art, however, the endearing humor provided by putti was also a way to alleviate the seriousness of Catholicism. Manneken Pis, Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly and Luther’s Reformation were just around the corner.

I don’t see a sacrilegious intention here; just the playful sense of humor that flourished in 15th century Europe. I have the feeling historians think no one had a sense of humor in previous centuries. In the Renaissance period, and for centuries to come, many little boys gathered around Aphrodite/Venus and the Madonna and child, and no doubt this reminded adults of children everywhere who were wondering about the new arrival in the family - like the famous Raphael fresco at the bottom of this page, or this Auden poem:

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen...

But it was little boys peeing - usually in fountains - which are the most interesting examples of the Fool. “Pueri mingentes” (from Latin), as they were called, became popular first in Florence and then across Europe. There is a direct line here to “young-ish” trickster figures like Shakespeare’s Puck and Ariel, who don't want to take anything seriously. But they didn’t last of course; by the 19th century, the tricksters had been pushed aside by the sentimental hordes of fairies, sprites and water babies.

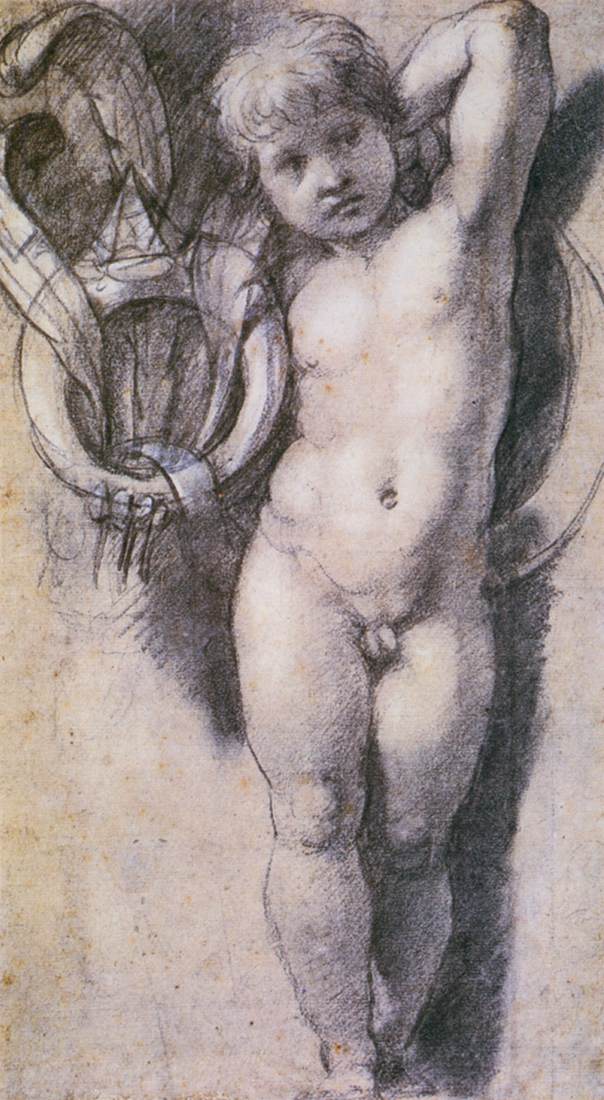

I recognize that some putti come across to a modern sensibility as porn, especially in the wake of the sex scandals of the Catholic Church. It's just an opinion though, and not one I share. It's an eye of the beholder thing. Consider this Raphael putto and you be the judge.

Also see:

Jean Fouquet: Melun Diptych of the Virgin and Child Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim (circa 1450) here

Titian: Assumption of the Virgin (1516-18) here

Lorenzo Lotto's Venus and Cupid (1520's) and Angelo Bronzino's A Triumph of Venus (1545) here

Rubens: The Abduction of Ganymede (1635) here

François Boucher's putti (1759) here

Charles Kingsley's The Water Babies (1862-3) here