Disease in the History of Painting

In medieval times, there was a widespread belief that signs of physical corruption mirrored the state of the soul. Bad people were ugly or sick. That view is still around today. But, following St. Augustine and Aquinas, and their classical Greek sources, it also was argued that all of God's creation was beautiful and it had a purpose. You can see an embodiment of that debate here.

The growth of science in the 17th century pushed that debate aside. For example, the menace of the plague can be sensed everywhere in earlier 16th and 17th century art (Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder). But, in the 17th century, painting began moving away from allegorical/religious and social visions to individual portraits and, if there is one painter who stands out after Leonardo for his remarkable drawings and portraits, it's Rembrandt. His paintings - including the self-portraits - have been detailed enough to fascinate physicians for years. They have found signs of eye problems, depression and cancer as they speculated about how he died and how others in his paintings have died.

Above is Rembrandt's The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632), which indicates he too must have been fascinated by the subject of disease and what to do about it. But I also have the impression that he really was more interested in the living, in survivors, in the mysteries of those diseases that afflict us in the here and now rather than why we die. In his paintings it feels like the age of science already has arrived. He lost his first wife to TB and his later common law wife to the plague and only one of his five children would outlive him, but his work bursts with life, not death. Consider this Rembrandt painting of The King Uzziah Stricken with Leprosy (1635).

Or this portrait (circa 1665) of fellow painter and art theorist Gerard de Lairesse who suffered a disfigured nose from congenital syphilis.

Disfigurements must have posed special challenges for court painters. Anthony van Dyck was accused of making his subjects look better than they were, but what if one's subject was really ugly? Later that century, there were the portraits of King Charles (Carlos) II of Spain. This one by Juan Carreño de Miranda in 1685 shows the King's misshapen face. The King suffered from innumerable ailments, mental and physical, too many to mention...

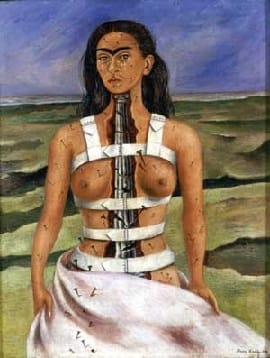

Also see here and here, plus the horrors of TB here and the pain of Frida Kahlo here: