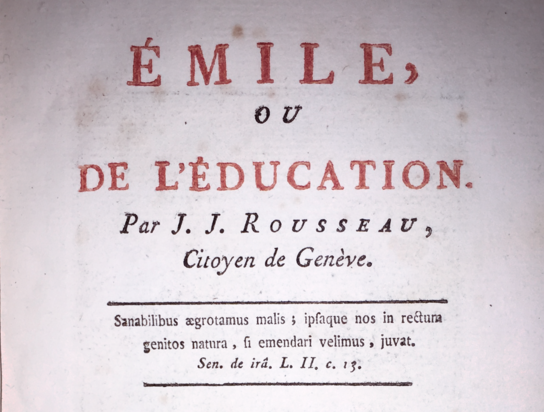

Rousseau's 'Émile, or On Education and Illegitimacy'

The revolutionary impact of Rousseau's Émile, or On Education (1762) lay in the implication that if we are all born equal ("In the natural order men are all equal"), then there is no inherent difference between a child born illegitimate and a child of wealthy, even royal, parents. No wonder the book was suppressed. It spread anyway as good books do, inspiring Thomas Jefferson, Tom Paine, William Wordsworth and Johann Pestalozzi.

Could you teach this boy?

Rousseau decided that his "imaginary pupil," Émile, should be an orphan, rather than a bastard. If he was to have any hope of his educational ideas being taken seriously by wealthy people, he needed to elide the question of what had happened to Émile's parents. So Émile embodies Rousseau's thesis literally: "We know nothing of childhood; and with our mistaken notions the further we advance the further we go astray." Indeed, we know nothing about Émile and the more we read about him the further astray we go! Typical Rousseau irony.

The painting above is Portrait of Auguste Gabriel Godefroy (Jeune Ecolier qui Joue au Touton) by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin around 1735. It is in The São Paulo Museum of Art.

Rousseau provides us with the world's first comprehensive guide to education, but he also covers parenting (birth mothers nursing their own children, doing away with swaddling clothes, observing a healthy diet, etc.). In doing so, he encouraged French families to value the children they had rather than discard the ones they didn't want. He also may have affected French sexual practices like birth control or, more specifically, coitus interruptus, since the French birth rate actually declined into and throughout the 19th century.

Nonetheless, according to historians, western Europe experienced an explosion of illegitimate children after 1750 that would peak around 1875 and then slowly decline, along with the birth rate. (The notable exception was France). Given that most people never married (marriage was an upper class privilege), then logically speaking it could be said that most people were "illegitimate" and that this was really normal population growth. The illustration above is The Pied Piper of Hamelin (1888) by Kate Greenaway for the Robert Browning version of the tale.

This was reflected in literature. The great middle class novels of the 18th century were not about bastards who might make a claim on inheritance, but "foundlings" - Émile, Tom Jones and Candide, for example - which disconnected them from parentage and ancestry and thus any inheritance. Foundlings were really plot contrivances, tabula rasa, for whatever moral philosophy you wanted to articulate.

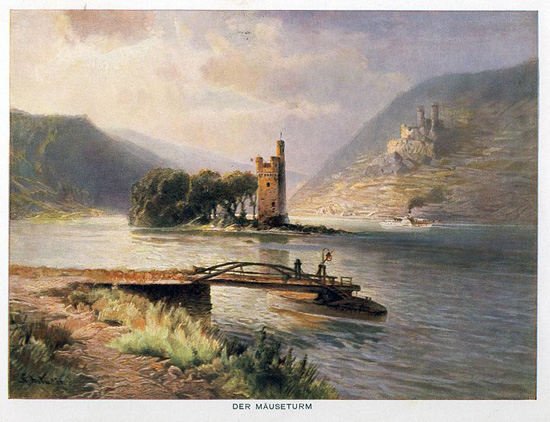

If you are curious about the source of the Pied Piper tale, it seems to be derived from a German folktale about the terrible end of Hatto II, Archbishop of Mainz, who (deservedly) was eaten by mice in the Mouse Tower (Mäuseturm ) in the Rhine near Bingen in 974. The painting below Mäuseturm bei Bingen am Rhein is by the Russian painter Nikolai von Astudin in 1920. Late in life Astudin was known for his Rhine paintings. The Tower is still there today.