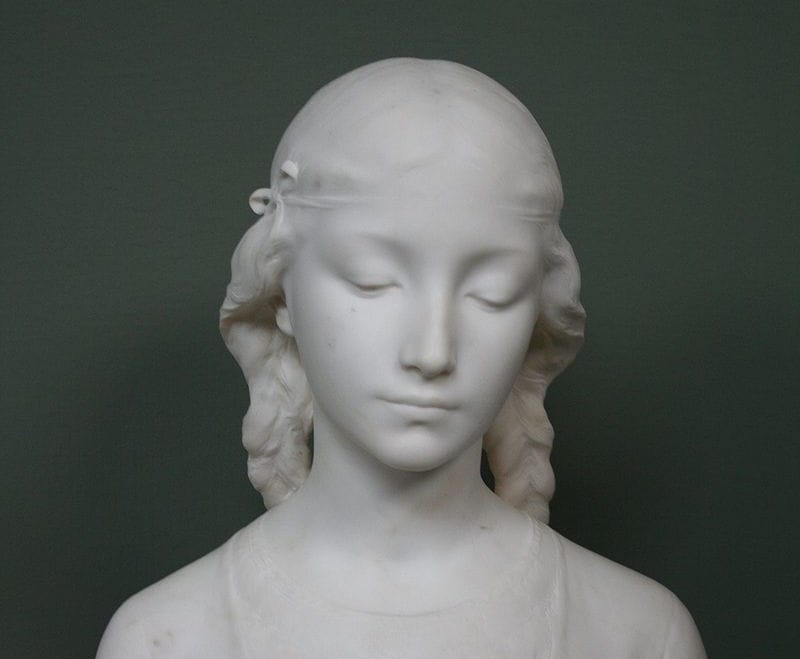

Gretchen is the hero of Goethe's 'Faust'

In Germany these days there is a debate about whether schools should stop teaching classics like Goethe's Faust. After all, "in Berlin for example, 55% of all children and teenagers have familial roots outside of Germany, according to Berlin's statistics office" (source: Deutsche Welle). I'm with the students on this: make education more relevant to their lives. Would Faust survive this?

The character getting academics' attention these days is neither Faust nor Mephistopheles; it's Gretchen, aka Margarete, whose story really is a tragedy. (Gretchen is a nickname for Margarete, and both are often shortened to "Grete." Goethe uses both names throughout the play.)

A modern feminist take might describe Faust, as a Guardian writer did recently, as

a teenage girl groomed by the old man, impregnated and socially ostracized. Her solution? She drowns her 'illegitimate' newborn child, accepts her death penalty and rejects Faust’s offer to save her from prison. In God’s mercy, the Christian girl seeks salvation and off goes Faust with the devil to new adventures in Faust, Part Two.

That could work as a school text. :) In this view, Gretchen is just a story contrivance, a traditional 19th century madonna/whore and tragic heroine created by - of course - a White male writer.

The other traditional Christian view is that, no, Gretchen is innocent and pure, a natural and feminine young woman who is corrupted by Faust, a selfish man in the grip of his lust and ambition. Many painters do allow that Faust may have been in love with her, which maybe lets him off the hook, Ary Scheffer for instance:

Both antagonistic views oversimplify. I think it's better to argue, as Maike Oergel does, that Goethe's Gretchen/Margarete and Faust aren't so different:

Margarete's aspirations and behaviour mirror Faust's own regarding a shared readiness to rebel, break all the rules, and dare the ultimate, which gives Margarete her own independent agenda, makes her an individual in her own right.

I prefer this view because it doesn't reduce this key character to being either an eternal victim or a story contrivance. After all, literary analysis is always projection, so if we are going to do it, why not project something we approve of. Some painters allow her this autonomy, this dignity, this in-between space, James Tissot for instance:

I think of this one as Gretchen on her mobile phone:

It's true that everything goes awry for her, as events cascade out of control, as they can do in our own lives. For example, the Guardian writer points out that Germany still outlaws abortion in the criminal code, so Gretchen's story holds true for today - her lack of options and her punishment. Unfortunately, many painters went with the imprisoning stereotypes, including Delacroix and the two shown below, Nicaise de Keyser and Ary Scheffer.

Often overlooked though is that Goethe grants Gretchen salvation at the end, no thanks to Faust. Whatever one's beliefs, none of the other characters receive it in Part I, which in my view makes her the hero of the story. Indeed, it's only because of her salvation that Faust too can be saved, at the end of Part II.

On balance, I think Faust can be taught successfully in German schools, but - like anything - it's all in how and why it's taught. Make it relevant to today's students.