Hildegard of Bingen: Sex in the Middle Ages

The most influential religious women of the medieval era worshipped the feminine spirit associated with the Virgin Mary rather than Mary Magdalene. Consider the great 12th-century German abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), a contemporary of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Bernard of Clairvaux (both of whom she corresponded with). She founded her own convent on the Rupertsberg, above a bend in the Rhine at Bingen, in 1150. It no longer exists but it is shown above in a visual reimagining.

Hildegard was very forthright about the dangers posed by sexuality, but she had a woman’s perspective:

"...a woman who takes up devilish ways and plays a male role in coupling with another woman is most vile in My sight, and so is she who subjects herself to such a one in this evil deed..."

"...And men who touch their own genital organ and emit their semen seriously imperil their souls, for they excite themselves to distraction; they appear to Me as impure animals devouring their own whelps, for they wickedly produce their semen only for abusive pollution..."

- (translation by Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop)

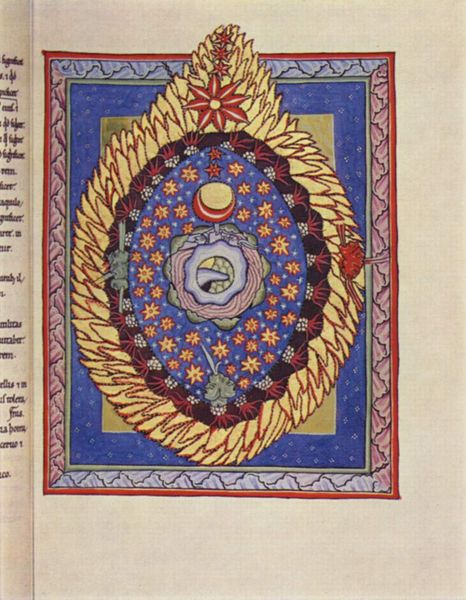

If Hildegard condemned homosexual behavior and masturbation (along with the ordination of women) and praised virginity instead, many nuns in the world of the medieval monasteries found a place for Mary Magdalene’s message of playfulness and sexual curiosity that always came along with her penitence. For example, what should we make of the illustration below, from Hildegard's Rupertsberg Codex, Scivias (from 1151 or 1152), which shows "The Universe" in the shape of an egg. Is this a sexualized image?

For where this image evolved to, see the bottom of this page, here... Or read up on Rabelais' story of Hans Carvel's Ring, which is a ring similar to the one shown above - one in which the jealous man can put his finger in to keep it safe. It's in The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel (in Le tiers-livre de Pantagruel), but Rabelais found it in earlier sources.

One of the most interesting writers on medieval sexuality is British historian Katherine Harvey, whose book The Fires of Lust: Sex in the Middle Ages (2021) covers everything: how oral sex and masturbation were not as popular as they are today, menstruation and menopause were considered disgusting and, my favorite, men had to avoid excessive effort during sex, because that was considered adultery with one’s own wife. I'm quoting one of the book's reviewers here, Jacinto Antón, in El País, who adds: "it appears that many people did not really understand what they could do with each other."

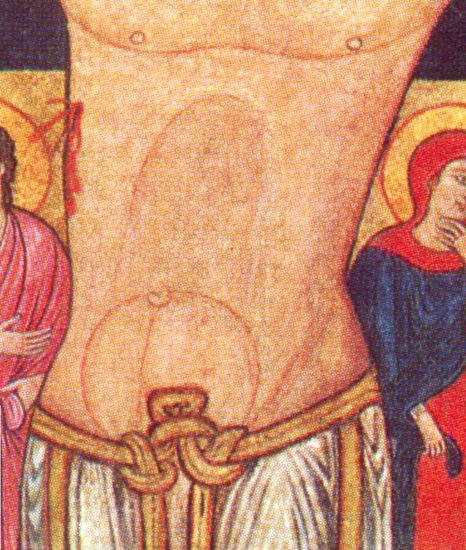

There is an equivalent debate over Christ's penis, which appears in religious art like the one below (from 1378). The debate among academics isn't over whether that's really a penis. It is. The debate is over what this sexualized image meant back in medieval times. They seem to be able to agree that these erect penises forcefully affirm Christ's physicality, potency and celibacy and that these medieval artists really pushed the boundaries of art. But feminist academics in particular caution against over-emphasizing the penis at the expense of other sexual iconography. Compare it with Egyptian and Greek penises here and here.