Homer's Women

Why did it take Odysseus 19 Years to Get Home from Troy?

Why did it take Odysseus 19 Years to Get Home from Troy?

Once upon a time, in the middle of nowhere, a middle-aged man washed ashore on a lonely island. Almost 19 years earlier, he had set out from his home to fight at Troy, but Troy fell 10 years ago and now nine more have elapsed, and still Odysseus hasn’t reached his home on Ithaka, his wife Penelope and his son Telemachus.

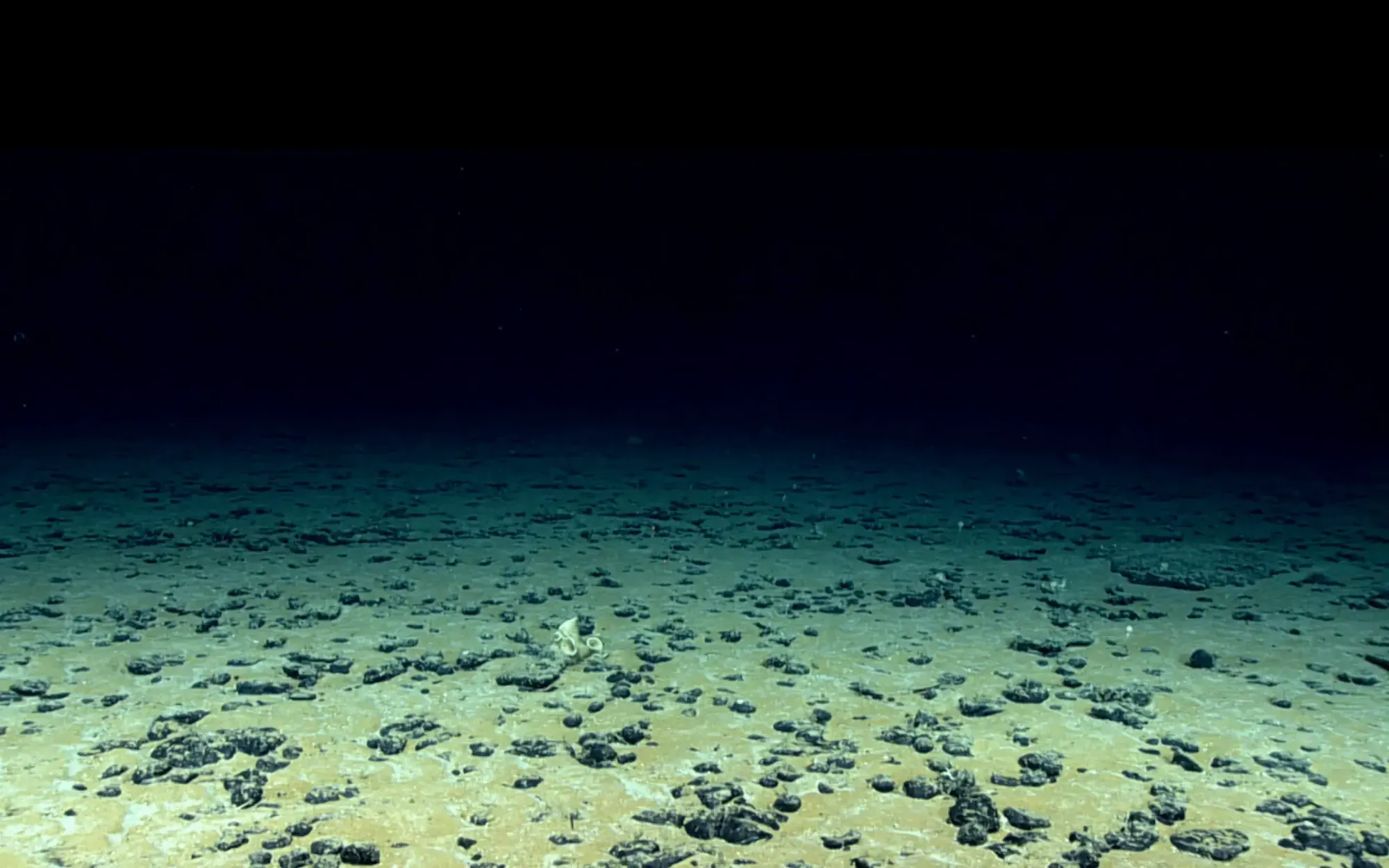

The journey from Troy would normally take three weeks in good sailing weather, across the Aegean Sea, around Cape Malea and up the Ionian coastline to Ithaka. But Odysseus has angered Poseidon and the sea-god has killed off his men, banished him to his fate as an eternal wanderer, a refugee, an exile, never quite home. In many ways he is a modern figure, who appeals to 21st century daydreamers in much the same way he did more than two and a half thousand years ago when storytellers recited the Odyssey from memory.

Odysseus is a symbol for the earth’s peoples who have been scattered across its seas in an earthly version of the Big Bang. We live now in an age when the old gods from the ancient times have been toppled – Poseidon is dead – and now man hopes, fears he has become god. Yet the Odyssey is modern in quite another sense: isn’t it fair for the modern reader to ask whether Odysseus also prolonged the journey for his own reasons? The women he met along the way, perhaps?

Calypso

The ancient gods were afraid of Calypso, of what she would do if mortals started drifting ashore on her island of Ogygia. Most men, upon encountering her, would never return to their wives. Once word got out, other men would be abandoning their wives and going in search of perfect women and who knows where that would end?

Only one man was ever washed ashore though, and when he was, Odysseus was impressed. Homer writes that Calypso was “a nymph, immortal and most beautiful, who craved Odysseus for her own.” She must have been an appealing sight for a man in middle age. She did not wear on his nerves as the witch Circe had done the year before. She did not grow and change and mature as the young princess Nausicaa would do. She would not judge him or seek to control him in the way his wife Penelope would do. Was she the perfect mate? Does a wise man really seek the perfect woman and if he does, is he wise to? Do only fools believe in perfect soul-mates?

But seven years have passed on Calypso’s island and he is marooned. One day, with Poseidon away from Olympus in distant Ethiopia, the goddess Athena, Odysseus’ protector, quickly petitioned Zeus and the other gods to rescue Odysseus from the grasp of Calypso. In the ancient Greek world such decisions required consensus. Zeus and the gods agreed that something must be done and Hermes was dispatched to inform Calypso that she must release Odysseus. Did Odysseus really beg the gods to allow him to escape from Calypso or is that Athena’s version of the story? The later parts of the Odyssey are narrated by Odysseus himself, so we don’t know who is telling us this first part of the story when it claims “his heart (is) set on his wife and his return.”

When Hermes comes to Calypso to release Odysseus, she protests “You gods are unbearable, in your jealousy: you stand aghast at goddesses who openly sleep with men, if ever one of them wants to make a man her bedmate.” Her strength and her independence shake the foundations of the ancient world and its patriarchs. Perhaps only a goddess could say such things to a god; a human woman would not have dared. But the decision of the gods is final.

Calypso sits in her garden at the edge of the cave she calls home. The air is thick with the scent of flowers and a natural spring trickles past her feet. The birds are singing, she has a great fire blazing. She moves to her loom, weaving and singing, in the hope he will decide to stay of his own choice. She weaves the siren threads of domesticity, contentment, stability, the rejection of warfare and men’s pursuits. Calypso even promises him eternal youth, immortality like her own yet, instinctively, he finds it all too feminine, too suffocating, and he wanders away through the trees to the stone seat on the cliff top to “scan the bare horizon of the sea.” Toward the end they had almost been fighting: “long ago the nymph had ceased to please.” He had begun to avoid her and just sat staring out to sea the way he always did when he was homesick. That is what everyone does sooner or later when lovers grow apart – they stare out to sea -- and even perfect sex and ambrosia aren’t enough in the end. There has to be friction.

So, like the mistress who watches her lover go home to his wife, Calypso watched him go on the morning tide. She would not have helped him build the raft. He did not say goodbye and she did not seek him out to make him say it. Seven years together is a long time and some things are better left unsaid.

Odysseus knew that he must move on. This was just an interlude in the natural progression from birth to death, where we are all alone to pursue our fates. He chose to leave, and that is why the gods helped him, and why Calypso gave in. Although a goddess, she did not do it without experiencing a deep anger. But she understood his wish to grow old, to experience conflict and heartbreak again, to step out of the stillness into the "black ocean" streams that will take him homewards, the “following wind” on his shoulder. The cycle of life should not be interrupted for too long or the poem itself is threatened. If Odysseus had stayed with Calypso there would be no poem.

Perhaps for this reason Calypso has never won the hearts of the male translators who over the years have had quite definite ideas about getting Odysseus back home to Penelope. Some have played up the psychoanalytical implications: did Calypso’s island remind him of the womb he was running away from all his life? Certainly Odysseus complains of the pains of rebirth that were deferred constantly while he lived with her. Many have claimed that her name means “enfolding” or “concealing,” even “obliterating” – all sexual metaphors of the kind popular with psychoanalysis. Or was it that the thread she wove – the myth of the perfect relationship, the perfect woman – would mean that he would lose everything else that made him a man?

There is a fundamental sadness associated with Calypso. She has never been invited back into other myths and legends. Arguably, one could say that she reappears in the distant future as the mysterious and the lonely enchantress the Lady of the Lake in the legends of King Arthur, Venus in the Tannhäuser legend and perhaps in Tennyson’s more vulnerable The Lady of Shalott. Goddesses who defy time and space are rare in western literature. They don’t get married and they don’t have kids but they probably want them (The Lady of the Lake kidnaps Lancelot as a child). They just pop into stories occasionally and then disappear again, which is totally unfair of course. Odysseus had had a child and fulfilled his debt to society so why couldn’t he have stayed with Calypso and had another child or two? The critics would have us believe that her dangerous appeal lies in her timelessness, the oblivion, the denial of self, and these can be a powerful siren call in the 21st century when many western men no longer know what they want. However, one could equally argue that second marriages are just fine, thanks, and Odysseus would have been happy with her if only the storyteller had given him a choice in the matter.

Circe

Before Odysseus ever got to Calypso’s island, he stayed a year with another beautiful goddess, Circe, and how different she was from Calypso. When his black ship first encountered her island of Aeaea, he had no idea where he was and we don’t either, but he still had his crew with him when he arrived.

Odysseus sent an advance party inland to scout out the island and they soon found Circe, the sea witch, who entertained the bullies hospitably. She fed them, sang to them, flirted with them, all the while encouraging these distant travelers to forget their homes and their wives. That’s one of the paradoxes of travel; it always reminds you of the home you left behind. But it can be assuaged with alcohol and sex and drugs, and Circe knew her drugs. When she waved her long magic wand, presto, she turned them all into grunting swine, the archetypical image of men in the thrall of sexual heat. If this isn’t the origin of the term “sexist pig,” then it ought to be.

Could Circe ever find a real man? Eventually Odysseus came looking for his crew and he seemed to know how to overpower her sexually. This was only because Hermes, sneakiest of the gods, gave him an antidote to her drugs and no doubt some precise instructions on a seduction sequence that would appeal to her. The antidote turned out to be moly, a small herb black at the root but with a milky flower (garlic, speculate the scholars). Circe liked a natural man, an earthy man, a man who was a match for a fertility goddess. She lived in an open plan house of well polished stone and shiny doors surrounded by forest and she could charm wild animals – the wolves, the lions who lived on her island – and so too she charmed Odysseus. Into her arms came this rugged handsome fellow, his hairy chest guarded by those piercing eyes. He was wiry and weather-beaten, like a hunter, hard, tangible, scented. Her erotica must have a touch of the perverse and she made love that way. In her terrific bed he learned of the future frights he would encounter with similarly dangerous feminine figures: the Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis. She taught him to understand that these are all projections of masculine fear and disgust with women’s sexuality. Men must learn to hate themselves before they can love women. Odysseus went along with it for a whole year and it was only when his crew became impatient that he agreed to leave.

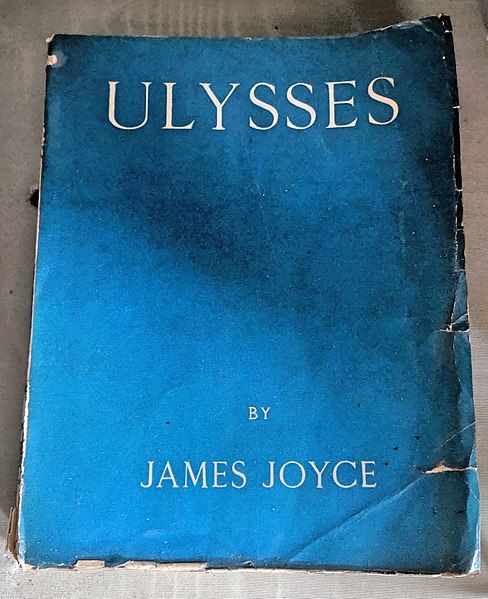

There was a lot of sexual tension on Circe’s island and this appealed to late Renaissance witch hunters who found Circes (and Medeas) everywhere, but she had her defenders, like Torquato Tasso and Giordano Bruno. But it was modernist writers such as James Joyce and Ezra Pound who fully embraced her. The Circe of Joyce’s Ulysses is a nightmarish hallucination of role reversal and sadomasochism. Circe puts in an appearance as Bella Cohen, mistress of the local whorehouse, helping Bloom get in touch with his feminine side and satisfying his longing for punishment by turning him first into a woman and then into a pig! Only through ritual humiliation and castration can Bloom emerge out the other side purified and ready to go back to his wife. Why he needed to go through all this and why he needed to be Jewish, we will never know, but it seems to have been important to Joyce. Ironically, Ulysses was published originally by two women (the American Sylvia Beach and her partner Adrienne Monnier), who launched it in France, in the English language no less, in 1922. They succeeded where another woman in England and two women in the United States had already tried and failed. Beach got no satisfaction for her pains; Joyce took the money and ran. But why should she have been surprised? The lessons were there in the novel.

Circe was also Ezra Pound’s favorite in The Cantos of 1948. She was his compromise halfway between those flirtatious bitches the Sirens and the unattainable goddesses Aphrodite and Athena. Circe represented the sensual world, she was seduction, she was the sexual act itself. It’s no coincidence that when he wrote The Cantos, Pound was still living with his wife but seeing his lover, Olga Rudge. So again Odysseus takes center stage: he enjoys his time with Circe but apparently it was necessary for him to transcend the merely sensual and return to his wife.

Feminist writers eventually came to rescue Circe, and if Penelope is their choice today, Circe was their favorite in the early fifties, particularly for Southern women writers. Eudora Welty’s Circe has magical powers and a wicked sense of humor. A fifties housewife, she has discovered feminism and is just waiting to take flight. Resentful at being tied to her island, she wishes she could be a wanderer like Odysseus: “Ever since the morning Time came and sat on the world, men have been on the run as fast as they can go...” But, alas, to be unappreciated by this magical wanderer: “I swayed, and was flung backward by my torment. I believed that I lay in disgrace and my blood ran green, like the wand that breaks in two. My sights returned to me when I awoke in the pigsty, in the red and black aurora of flesh, and it was day.” In the end, it is Odysseus who leaves and Circe who stays, “sickened, with child.” It is a powerful story with great expressiveness but no feminist breakout here; we have slid back into the kitchen sink of melodrama with its hurt, malice and rejection, where men are always beasts.

Margaret Atwood’s Circe is more resentful still: “One day you simply appeared in your stupid boat,” and the relationship careens downhill from there with a strong suggestion of violent abuse: “Holding my arms down/holding my head down by the hair/mouth gouging my face/and neck, fingers groping into my flesh.” Did Odysseus try to rape Circe?

Then there is Katherine Anne Porter’s Circe, a “beautiful, sunny-tempered, merry-hearted young enchantress (whose) unique power as goddess was that she could reveal to men the truth about themselves by showing to each man himself in his true shape according to his inmost nature. For this she was rightly dreaded and feared; her very name was a word of terror.” Porter allows Circe to have sexual power, a casual black humor, all the better to deal with the wily Odysseus. How dare he act cold and aloof in bed when she is tender and loving. How dare his men complain to him behind her back about how bored they are on her island. They are lucky to get fed at all! If Circe enjoys superiority over the weakness of men, it is not in an arrogant or egocentric way; it is simply that she is smarter than they are. One day, will Odysseus see that and will he be back, alone? Isn’t this what wise men want: wise women?

Nausicaa

Nausicaa was with her handmaidens throwing a ball around down on the beach. Several were washing clothes nearby when Odysseus appeared out of the bushes with no clothes on. Just an olive branch held discreetly in front of the embarrassing parts.

It must be quite difficult to listen to a naked man and take him seriously, but Nausicaa was nothing if not modern. “Does the sight of a man scare you?” she asked her handmaids. But they fled the moment the olive branch slipped a bit. She called after them, “Would that such a man might be called my husband,” which may have been an indiscreet thing to say since she was single and it set off another round of gossip. Her friends and family were all saying she was beautiful and that she had a sweet nature but this hadn’t got her a husband, had it? Was he the One? Nausicaa arranges for Odysseus to go into town to meet her parents, the king and queen, where he can tell his story for posterity and she says she will follow. No need to feed the gossips by going together.

When Odysseus washed up there on her island of Scheria, here was an opportunity to be had. Did she miss it? Should she have invited Odysseus to stay with her? This is her first and last appearance in the Odyssey but on such flimsy material Samuel Butler decided in 1897 that she must have written Homer’s entire poem. His case is built on the fact that most of the Odyssey is told – by Odysseus – in the palace of Nausicaa’s parents, so clearly she was there to hear it. This also encouraged Robert Graves to expand on it in his novel Homer's Daughter (1955). Other male translators have confessed their love for her in suitably extravagant terms -- Japanese animation genius Hayao Miyazaki takes her name for one of his heroines. What is a girl to do? Would Nausicaa have preferred being given credit for seducing Odysseus or for having authored the Odyssey? Does the Odyssey actually have a woman’s point of view? We don’t know who Homer was or even whether Homer was many people, but some claim “he” was blind, because he may be the blind storyteller who appears in the Odyssey at this point. But the thread being woven here is the one that is not being woven: Nausicaa never weaves a story herself. She is still young, unmarried, tabula rasa for an old married guy like Odysseus and maybe she never could have worked out as a marriage partner for him.

One imagines that if she had indeed written the Odyssey, she would have written herself a bigger and better part. She would have developed it as a subtly erotic encounter between a man who was nostalgic for his lost past and a young woman looking for a real man. It would not have been filled with vulgar sex, Circe style, but with suitably romantic scenes between two lovers who deeply respect one another. While that may have been Nausicaa’s fancy, was that Odysseus’? Sure, he would have been attracted to her but could it have lasted? That doesn’t stop her modern fans from having a riot anyway. In Joyce’s Ulysses she is played by Gerty MacDowell, who does a sentimental striptease in front of the hero Bloom while Bloom masturbates! Bloom is grateful for her helping him feel like a man again.

Nausicaa’s island is presented in more realistic terms than either the pleasant lonely reverie of Calypso or the tempestuous orgy with Circe. It is half way to Ithaka without any unpleasant complications such as suitors or an unfaithful wife. It is full of peace and plenty. She is, you might say, a very clever final temptation. It should have appealed to a middle aged man who sought to be rejuvenated by a younger woman. Isn’t that what all middle aged men want anyway? So why didn't it work? Because Odysseus wanted more than what a beautiful young woman wanted for him?

Penelope

Lawrence of Arabia (T.E. Lawrence) was one of the many translators of the Odyssey. So self-conscious was he about being the 28th to try his hand at it that he used a pseudonym, T.E. Shaw. What did that old misogynist see in the Odyssey that he wanted to translate it?

Was Lawrence attracted to Odysseus, that “cold-blooded egotist,” as a homosexual ideal? Did he like the theme of the wanderer and worry about the fate of manly freedom in a world of feminine distractions, the kind that were pressing in upon Lawrence in the aftermath of World War I. Disgusted by the domestic bliss that ends the Odyssey, he thought it a major anticlimax. He never thought through the situation, however, to refashion the story so that it arrived at a different conclusion. He was a traditionalist at heart. What if Lawrence had been attracted to women? Could he have matched Odysseus up with any of the women he met along the way -- the sea witch Circe, the lonely goddess Calypso, the maiden Nausicaa -- or was Odysseus always destined to return to his long-suffering wife Penelope? Were these women, including Penelope, merely femme fatales designed to tempt the hero away from the ways of the world back to the domestic life, to being no more than a good husband? Were they lustful and seductive, overly controlling, seeking to entrap our hero? Is entanglement just another way of saying fear of commitment? In the Land of the Dead, the ghost of Agamemnon, murdered by his wife upon his own return from Troy, says to Odysseus “Do not be too easy even with your wife, nor give her an entire account of all you are sure of. Tell her part of it, but let the rest be silence.” That was typical of Agamemnon of course – he just did not understand women.

The Odyssey is about more than just the return to house and hearth. It is about a man’s choice of ideal sexual partner, it is about the compatibility of sex and marriage, it is about how a man exercises his freedom before returning ultimately to where he started from. The Odyssey is about rebirth and the search for a new identity but it is also about loyalty. Now that he is middle aged, whom should he spend it with second time around if we were to give him that chance? What was it Odysseus wanted? What do men want? It would seem that Odysseus chose Penelope, his wife. Why?

It was all right at the beginning, but once Troy fell she had expected him home. They hadn’t been married long when he left and Telemachus was just an infant. As the years passed, the news stopped coming. She did a lot of crying. By the time Odysseus came home to Ithaka, he had been away 19 years and she had not had a sexual partner in all that time, she was losing her looks and feeling older, and she didn’t have a close confidante, a defender, a husband. She could fairly accuse him of desertion. Would any woman wait as long as she did? True, there were distinct advantages to being single, to being a widow. She was still comfortably well off, which made her a desirable catch for the suitors and at least she had a choice. She was flattered by the attentions of so many good-looking young men. In fact, this is what Antinous accused her of in public – that she enjoyed it – and this was true for a few years at the beginning. She had to adopt delaying tactics but she would never give in and choose one of the suitors because that would have brought the reasonably pleasant situation she was in to an abrupt end. And, she would have found Odysseus on her doorstep the next day! She also knew the other suitors and townspeople would criticize her the moment she chose anyone.

Penelope wove her web during the day and unraveled it at night. Weaving has been the work of women since ancient times and it is now a feminist metaphor for women’s creativity and the stories that were never heard when the focus was on the husband. Repression equals silence, as they say. Penelope’s quest was no different from Odysseus’ but she had no rudder – no god -- to guide her into the unknown. Her quest stands for the refusal of the violence that inhabits the men. Women will stop weaving only when the violence ends. Penelope chose to resist, weaving just the one story, a story that excluded the suitors. It is the unfinished story of women in a sea of men’s stories. Penelope is today’s single mother.

So she kept delaying even after Odysseus came back because she wanted to explore her own ambivalence about his return. Did she even want him back? He was in disguise but she recognized him immediately, even though the Odyssey is vague on this point. At the very least she wanted him to demonstrate to her that he was the same man, and perhaps also that she was the same woman. So she checked his memories, she insisted he shave and bathe, and she measured his performance in bed. She only agreed to recognize him after she had looked at his scar in that very private place. She handled this situation well and the characters of the Odyssey considered her wise.

In the end the gods had their own plans for them. Those plans required that the suitors all be killed and a bloody massacre was the result. Penelope felt no remorse over this sacrifice: the suitors deserved it. They had exploited her, eaten her out of house and home. It almost led to the slaughter of their relatives as well but the gods made it clear this was the end of the cycle. Odysseus and Penelope would live into their old age together.

Depending on how one looks at it, marriage in the Odyssey can be regarded as a degraded institution, a metaphor of death. How else can you explain Helen of Troy’s unfaithfulness or Clytemnestra’s murder of Agamemnon or Odysseus’ 19 years away? The Odyssey is not about the triumph of marriage after 19 years separation; it is about the fact that it took him 19 years to return. The women of the Odyssey do not entrap men; men entrap themselves in their own illusions and deceits. The Greek writers who came after Homer knew this; they were very cynical about Odysseus’ motives. Dante placed Odysseus in the Inferno for being a dissembler, for being dishonest, both with himself and with those he loved. Frank McCourt called him a draft-dodger.

For all the gods’ interference, Penelope held the future in her hands for a few hours and she could have chosen to destroy it as Clytemnestra did. The marriage survived only because Penelope chose to recognize her husband; imagine if she had refused him. This is the bittersweet taste that permeates the end of Joyce’s Ulysses, as Molly Bloom lies in bed reminiscing about life, lovers and Leopold Bloom snoring in the darkness next to her. She has hardly been loyal and faithful but she does still want to hold on to her Ulysses. And will Odysseus be gone again shortly and will Penelope sit there waiting for it to happen all over again as if it never ends?

Dante in the Inferno sends Odysseus off again with his crew, beyond the Pillars of Hercules and the equator where they all die in a maelstrom, just short of Purgatory's mountain. Tennyson's Ulysses wants once more "To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths/Of all the western stars." In Nikos Kazantzakis' The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel (1938), Odysseus leaves home for Sparta, Egypt and beyond, dying in Antarctica.

But these are the pessimists. Homer’s Odyssey can also be looked at as a reaffirmation of marriage and the loyalty that develops between spouses no matter what happens. Penelope is Homer’s image of feminine faithfulness. She is supposed to be powerful but melancholy. She is supposed to have great practical intelligence and the ability to think strategically. This is no better demonstrated than when she says “think what difficulty the gods gave [us]: they denied us life together in our prime and flowering years, kept us from crossing into age together.” These are some of the most powerful lines in western literature and they speak to anyone in middle age and beyond. Their message is unmistakable: the blame lies with the gods, not with ourselves.

The Passion Of The Christ

Perhaps the least appreciated aspect of the Odyssey is its foreshadowing of the most influential sexual fable of them all -- the Christ story -- which would also be written in Greek. The Odyssey and the Gospel stories are similar in that they are both spiritual quests, written with great power and drama.

They are also different, of course, in that Christ accelerates the process dramatically toward a confrontation with God, plus there is only one God and not many, and in the Odyssey there is no resurrection after death. But the similarities are stronger. For example, in Homer, Odysseus frequently is referred to as the “seed of Zeus” just as Jesus Christ is referred to in the New Testament as the Son of God. Both stories accept that life is a spiritual journey, where it is important to avoid the temptations of food, drink and seductive women. Maybe the Odyssey, like the New Testament, can be read in Augustinian terms as a story of conversion? True, Odysseus succumbs many times where the Jesus of the New Testament does not but then who’s to say? Maybe Jesus did sleep with Mary Magdalene? Modern writers seem more than willing to accept that Jesus encountered many beautiful women along the way and they argue that celibacy was Saint Paul’s (and later Saint Augustine’s) “contribution” to the Gospels and the Catholic Church.

Odysseus himself is a prototype of the Christ figure. First, because in always moving on, in seeking to return home, Odysseus chooses death, rather than immortality with Calypso. Jesus did so too although he may have believed that immortality would come to him anyway through the Resurrection. Jesus chose death on his own terms rather than life on somebody else’s terms, just as Odysseus did. Both choose death with an act of rebellion, a very human act. Also, “Home” might as well have been “Heaven.” Second, the trials Odysseus faces at the hands of the gods resemble the trials that Jesus faces centuries later in the build-up to the Crucifixion. In the Odyssey they are stretched out; in the Gospels most of the action is compressed into the Passion. Third, Homer allows Odysseus take revenge on the suitors when he gets home to reestablish the order of things but his true adversary throughout the book is the Gods themselves – Poseidon, Zeus, the Sun God. Jesus faces similar agonies where Caiaphas and the high priests may as well be the suitors carousing in Ithaka, but Jesus’ true adversary all along is the Jewish God himself and it is man’s assertion of divinity that is being tested here. “My god, my god, why have you forsaken me?” has always had a complex meaning, for Christ is challenging God himself to respond to him. Perhaps he never did?

We all come and go unknown

Each so deep and superficial

Between the forceps and the stone

- Joni Mitchell: "Hejira"

The most surprising thing that emerged in the debates about Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of the Christ in 2004 was how little the two religious communities, Christians and Jews, spoke to each other in the same terms. There opened up a vast gap that until then had been quietly repressed by mutual consent. This gap revealed how incomprehensible the other’s religion truly was. Despite decades of well-intentioned inter-faith dialog, Christians simply did not understand that the events of two thousand years ago mean very little to contemporary Jews other than as an excuse by Christians to practice anti-Semitism. This is primarily because dominant cultures or religions seldom take the time to learn anything about minority cultures or religions and the minorities often prefer it that way. Many Christians, raised with their own image of Jesus (as a warrior or effeminate or Black or tortured) have never understood what it meant that Jesus was in fact Jewish. Indeed some have expressed honest surprise when they realized this in adulthood. They had seen it but not seen it. Conversely, Jews simply did not understand, or perhaps preferred not to understand, the revolutionary symbolism involved in those events that sundered Judaism forever. They did not understand the role of self-sacrifice and martyrdom that are at the heart of the Christian religion and they wrongly focused instead on what they did understand: anti-Semitism. In Judaism, notions like martyrdom and self-sacrifice do exist, but in today’s religious context they sound like suicide bombers; they are incomprehensible and the equivalent of heresy. In Christianity they are symbolic of the human condition: Christ’s act of atonement was supposed to be an example for others, not to be followed but to be contemplated and rejoiced in.

What both communities have long had in common, ironically, is that neither fully came to terms with Jesus’ Jewishness. Sure, there were some rabbis through the years who argued that Jesus was, in fact, a good Jew, and should not be lumped in with what Christianity has become, but to most Jews he was a symbol of Christianity’s dominance and persecution since Roman times. Christians were forced to place the revelation of his Jewishness up against what they thought of Israel and the Jews in their own communities. Disbelieving Jews wrongly wrote this off as just another form of anti-Semitism (“how could they not know Jesus was Jewish?”). But Christians also failed to appreciate that early Christianity quickly became a Greek and later a Roman religion that systematically marginalized the Jews and their God as a competitor and that hasn’t really changed. Christianity eroded and displaced the pagan gods and became identified with European imperial power, spreading across the globe just as Islam would do centuries later.

The question of who killed Jesus is irrelevant if the prosecution and Crucifixion were violent Jewish events. Indeed there were no Christians at this point. In this story, then, it is God who kills Jesus and that’s its point. For those who are uncomfortable with the idea of a vengeful God, let me put it another way: if Jesus knew he was going to certain death, indeed he sought it out, is there any inherent difference then between martyrdom and suicide? Blame God or blame Jesus, if you must, but do not blame the Jews or the Romans.

Many would not agree with any of this, especially the idea of blaming God. Jewish services mention God frequently even if the main focus is on life lessons and the most sacred icon is the Torah scrolls. Christian services of all denominations, on the other hand, differ from this by emphasizing “Almighty God” with the tinge of a threat, as if we are still living in the Roman Empire and owe allegiance to Caesar, who was after all supposed to be divine too. Instead of the Torah, there is the sacrament (“communion”) of bread and wine, as if to remind the penitent and the sinner that this will be your body if you transgress. It wouldn’t be until the Reformation and the breakaway Protestant churches were formed that the emphasis would be less on God the Father and more on God the Son, less on Christ on the cross and more on the empty cross itself. Even Catholics have trouble understanding Protestant thinking; imagine how hard it is if you’re Jewish. It is not surprising then that the two original communities – Jews and Christian Jews -- have grown so far apart that their descendants have enormous trouble understanding the other’s ceremonies, iconography and symbolism.

Have we got a long way away from the Odyssey? Not really. One of the greatest failings of western philosophy is that it inherited the absolutism and authoritarianism of traditional Jewish and Christian religious thinking but discarded the multiplicity of views that the ancient Greeks identified with their many gods. The result has been an astonishing inability in the West at recognizing subjectivity. To pronounce an opinion on another culture should always be placed against whether one has the right to do so in any given context, and if one assumes the right, what does that say about you and your willingness to understand others? This is something that many non-western societies have always better understood because they have retained an appreciation for the multiplicity of viewpoints that derives from, for want of a better term, a “pagan” view of the world. For example, Maori people of New Zealand have the concept of turangawaewae, literally “a place to stand.” This term explicitly requires that before anybody opens their mouth in public, they need to identify themselves. In other words, the legitimacy of what someone says may be compromised by who they are, where they are from and why they are saying it. Although this principle is enshrined in western law (the concept of “legal standing”), it apparently does not apply anywhere else, for example, in letters to the editor about political or social issues that appear in our daily newspapers. Imagine if every letter carried an ID of ethnicity and religious belief: wouldn’t that explain a lot? The names and cities of the writers are not enough. Like Prometheus before him, Odysseus himself was one of the first to challenge those with pretences to objectivity, to telling “the truth,” to doing what you’re told because God says you have to. That’s what got him in trouble in the first place, but he did get home in the long run.