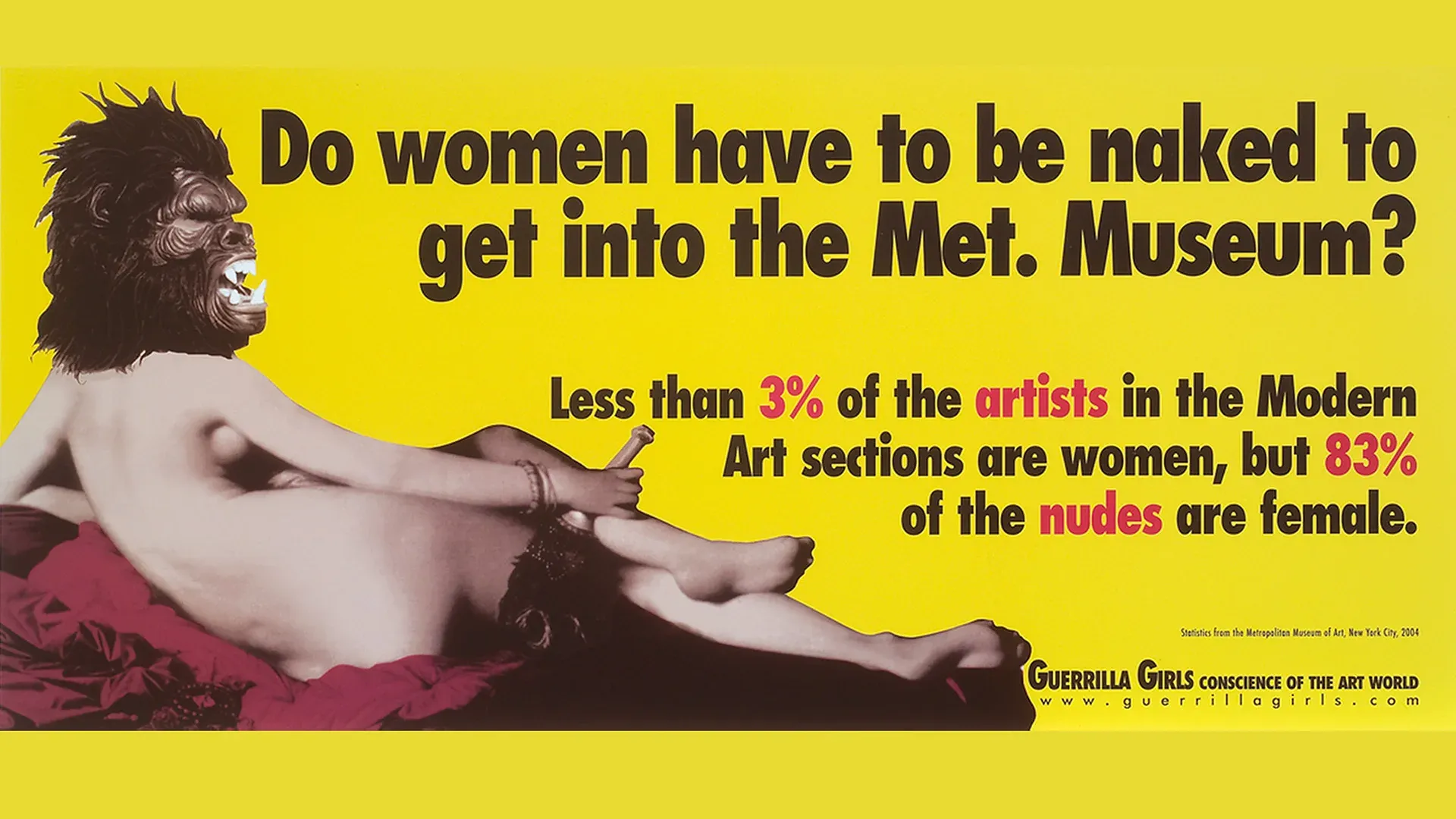

How to Look at a Naked Lady

How Lady Godiva Got a Tax Break

How Lady Godiva Got a Tax Break

Once upon a time Coventry was a nice quiet sort of place, when “being sent to Coventry” meant being banished to obscurity. Nowadays, the city has been struck by the tourism industry just as much as any other city as it strives to reinvent itself. Coventry now has an official Lady Godiva employed by the city council and the town is awash in Lady Godiva festivals and memorabilia – signage, souvenirs and knickknacks scattered around the city like mushrooms, along with the half-dozen local historians who have arranged for the story to be “authenticated.”

Coventry obviously has reason to be grateful for its Lady Godiva and her famous ride through town in the nude. But if that is so, why does Godiva no longer recreate her ride each year in the nude like she used to? These days she is fully dressed and, in this fitness-conscious age, they have even added a half marathon in her name. More importantly, why have the citizens of Coventry banished their other famous citizen, Peeping Tom? Tom was the only person who dared to ogle Godiva and he is one of the few references to illicit looking that predates the scientific and legal revolutions of 18th and 19th century England, when “looking” became rude, even pathological. Indeed today, while some people still use the words “peeping Tom,” he has mostly been pushed aside by more fashionable words like “voyeur” and “pervert” and "predator," first in academic writing by way of Freudian psychoanalysis and later in psychology, journalism and popular writing. Godiva’s reputation, on the other hand, has soared, but the most interesting aspect of her ride nowadays is that it is no longer politically correct to have her in the nude. So what is going on here and who should we believe? Why did Lady Godiva ride through Coventry in the nude in the first place and did Peeping Tom indulge in a spot of voyeurism or has he been unfairly maligned?

LADY GODIVA’S STORY

Back in the 11th century, the Lady Godiva, as Countess of Mercia, had personal charge over the good people of Coventry. When these extraordinary events took place, they were being burdened terribly by taxes. In order to arrange for tax relief, she needled her husband Leofric at every opportunity until one day he made her a rash promise. He would grant her request to lower taxes only if she rode through town naked.

Clearly Leofric meant it as a joke for he considered his wife to be practically a religious fanatic. So the very idea that Godiva would agree to his challenge took him completely by surprise. For the record, the real reason she rode naked through Coventry is that she did it for her people. There was no other reason. But there is simply no escaping the fact that she was driven to these desperate lengths by a husband who consistently refused to listen to her perfectly reasonable requests. He was your usual paternalistic man. He elevated the female body to almost mystical heights, which is why he conceived of the wager in the first place, but he was totally unable to deal with the real woman inside that body.

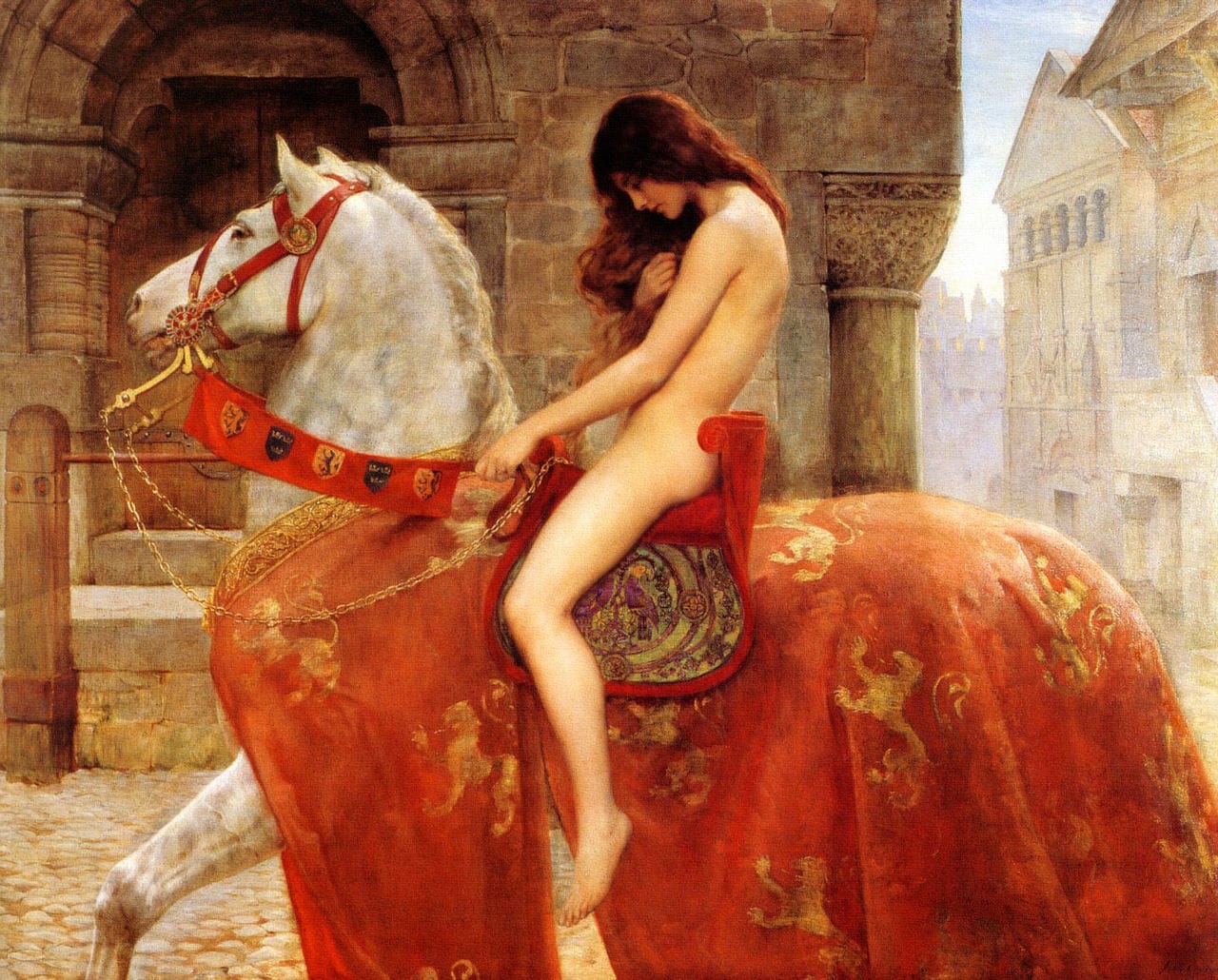

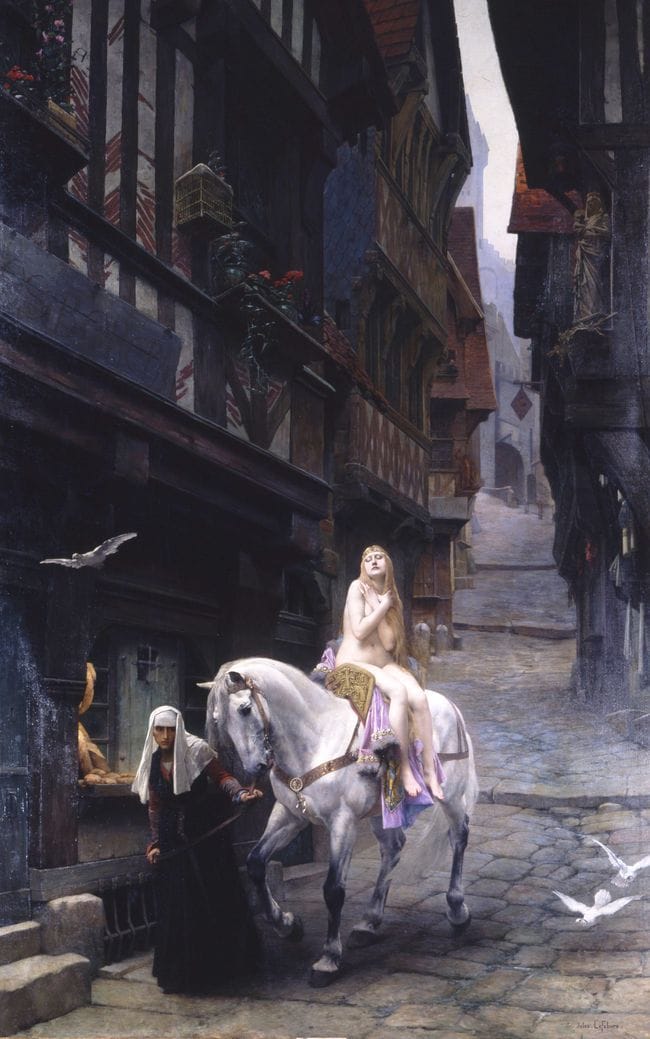

Godiva planned her insurrection carefully, to ensure it would play out the way she envisaged. She was thinking it over when she remembered all the artists who had portrayed Mary Magdalene in the nude, covered only by her long flowing hair. It was then she decided that riding through the town in the nude would create a double image: her nudity would be interpreted as a sign of her humility and repentance before God and as a sign of her sexual allure. She was certainly not ashamed of her nudity. Long hair expresses a woman’s sexuality and hers was not dead yet, whatever Leofric had to say about it. In fact, she enjoyed flaunting the very thing Leofric thought he had the most under control – her body. Did she do it to get back at her husband? Yes of course. This was his idea in the first place. He set the challenge because he did not think that his virtuous wife would dare and perhaps also because, as the years passed, he had grown to have less respect for her. She wondered if he cared either way. However, she knew he was shocked when she accepted the challenge and that’s when he tried to add more conditions. He argued that the ride had to be through the crowded market on fair day, but she objected that that wasn’t part of the original challenge. She felt that when it was over he had to be rightfully humiliated. And that is what happened.

After the infamous ride was over, the official view around Coventry was that she had risked her virtue and reputation for a worthy higher goal. Her husband Lord Leofric, Earl of Mercia, would be the first to concede that there is no higher goal than a tax break, but he was shocked and disappointed when she displayed her body in public. He was, after all, one of the most powerful men in Anglo Saxon England and he had an image to protect. He was responsible for governing most of the western and central region, which meant he had to raise taxes for the king and this he did, efficiently. His wife, the Lady Godiva, on the other hand, was practically a saint, and he had only meant that if she was really keen to do something for her church and her people, she should have stripped herself of some of her possessions, not the clothes she had on. He had meant her to face up to the fact that she had too many dresses and too many shoes and that she should have given some of them to the poor if she really wanted to do something practical! The whole thing had been a silly misunderstanding and now it was a national disgrace that would bring shame on Coventry.

In his heart, he simply could not fathom how she had come to do it. He knew Godiva to be a deeply religious woman – she had an obsession with the Virgin Mary, rather than the wicked Mary Magdalene. He supposed she must have decided this was going to be a religious experience. Perhaps she saw an opportunity for sainthood since saints got the nod for a lot less these days. Once she got a lot of people around town talking about the power of God at work, then she got some of those foolish young monks over at the Benedictine monastery of St. Albans to spread the story around that she was a candidate for sainthood and that he was some stingy old fool. Monks are always looking for sexy stories in order to get a following, otherwise no one would listen to them. The whole thing reminded him of that story of the Emperor’s New Clothes except in reverse: she took her clothes off and had no one watch! Godiva was encouraging people to treat it as a religious experience when it was nothing of the kind and he had heard of at least one fellow who didn’t think it was either. That fellow had stuck his head out to have a look at her and now he was being persecuted by the fanatics from the local abbey – the same monks that Godiva had surrounded herself with.

Leofric was forced to pretend the whole thing was a miracle, which in a way it was, since almost no one did see her nudity. But the worst thing about this was that he had to grant the tax break. He doubted that Godiva gave a single thought to where he was going to raise the extra £5000 a year to pay for her extravagance. Women! This was not how a noblewoman should behave – it was undignified and unladylike – and he doubted he could ever trust his wife again. A woman should be subservient to her husband; she should not seek actively to humiliate him. As Ephesians 5: 22-23 states in her very own bible: “Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the Church.”

PEEPING TOM’S STORY

Tom the tailor looked out that window for perfectly innocent reasons. He had heard Lady Godiva’s horse neigh as she passed by and he was concerned to see if she was all right. Nothing wrong with a bit of neighborly concern, is there? Once he knew she was fine, he pulled his head in again and wondered whether she was truly naked. Well, who wouldn’t? It’s the natural thing to do.

Tom also had been curious to see whether Godiva was riding with or without a saddle because he was thinking that she must be very uncomfortable without one, and if she was riding English style she may have been exposing herself rather more than she intended. He thought she probably never gave any thought to those things. Even with the long hair over her bosom it can’t have covered everything, though a wig might have done the job he supposed.

How old was Godiva anyway? He never saw her up close. Was she worth looking at in the nude? She may have been in her eighties for all he could tell, but he did see that she was nude and he thought she was flaunting it a bit. He wouldn’t have been surprised if old Leofric looked at his wife in a totally new way after her ride and the whole episode may have done wonders for their marriage. A few moral types had argued that it was the horse that was naked, but Tom knew it was Godiva. He did see that much.

At any rate, Tom got struck blind for his pains, presumably by God, though who’s to say? Most of you readers will feel he deserved it no doubt because you think he really just wanted to look at a naked lady. But this is unfair. He had been out of town on business and had only recently returned that day and he had not heard about the ban on looking out the window. So his blinding is fairly severe punishment, don’t you think? All he could really see under her long flowing hair were her legs, but there is no one who can confirm his version since she arranged for the authorities to ensure everyone stayed indoors, and she did it so early in the morning that hardly anyone was up. The citizens cooperated only because they stood to benefit from the tax break.

All this took place not long before the Norman invasion of 1066, which upended Anglo-Saxon England. The Lady Godiva story probably was based on a folktale or earlier pagan fertility rites associated with the May Queen. Coventry is located near the Forest of Arden, after all, which has long been associated with pastoral myths – Shakespeare’s As You Like It for example. Mix it all up and shake it all around and you will extract the wonderful story of Lady Godiva. During the medieval period that followed, the monks were worried about the story’s sexual element and Robert Graves, in his book The White Goddess, suggests that they tried to clean it up. Some centuries later, during the puritan era, when the maypoles came down and the mystery plays and pageants were stopped altogether, Lady Godiva was another casualty.

Fortunately, with the Restoration of 1677, Godiva and Peeping Tom were able to make a triumphant comeback in Coventry and, for hundreds of years, Lady Godiva’s ride was recreated enthusiastically in the town with some young damsel being selected to play Godiva in the parade. The organizers usually got her from out of town to make sure no one knew who she was. People would have started assuming all sorts of things otherwise. The most hotly debated topic every year was whether she would really be naked this year, and the puritans and conservatives always took a keen interest in making sure she wasn’t. But times change and so too do the traditions. Back in 1962, Godiva wore a skin-colored body suit and a long wig that covered most of her charms. Nowadays, with children watching, the official Godiva can flaunt it a bit when she wants to but it has become rather tame. In this age of image marketing, Godiva is still Coventry’s best tourist attraction and public nudity is left for other locals to show off.

On one thing the local puritans and the liberals all agree. Peeping Tom spoils the fun. The nickname has become synonymous with “pervert,” and all those moralizers and armies of senior citizens out there arguing that he was an embarrassment to the town have won. They have taken down most of his effigies, burnt his postcards and souvenir stands. He has no defenders, he has been almost completely banished. Hence the origin of the expression “Sent from Coventry,” which Tom’s enemies have managed to have reversed over the years so that now everyone says “Sent to Coventry,” meaning banished.

Tom may be just as ancient as Godiva. But the historians and folklorists tell us that the earliest reference to him that they can find belongs to the 17th century antiquarian William Camden, just before the Restoration of Charles II. It was probably a joke explanation for the blank unseeing eyes and agonized expression Camden saw on a 500-year-old wooden statue of a man who was supposedly Peeping Tom (shown above). Blank eyes because the paint had long since worn off! But the puritans drew other conclusions: blinding was an appropriate punishment for sin and that was that. The playwrights and journalists loved him though. Some pointed to the classical Greek story of how Actaeon saw the goddess Diana bathing and got ripped apart by her Rottweilers for peeping at her nudity. Tom was luckier and only got struck blind for his pains.

But that wasn’t the end of Tom. A comic opera called Peeping Tom of Coventry appeared in 1784 and there were dozens of pantomimes and burlesques throughout the 19th century, and even a Mascagni opera that was first performed in Milan in 1910. It wasn’t the German bombing in World War II that banished Tom from town. It was the historians and the feminists and the social workers, once they got a hold of him and dissected him in a fit of political correctness. Nowadays - at least since 2017 - he is reasserting himself in the public eye. While a few statues and effigies there once were in Coventry have disappeared, the few that remain now have their staunch defenders and Coventry celebrated 2021 as the UK City of Culture!

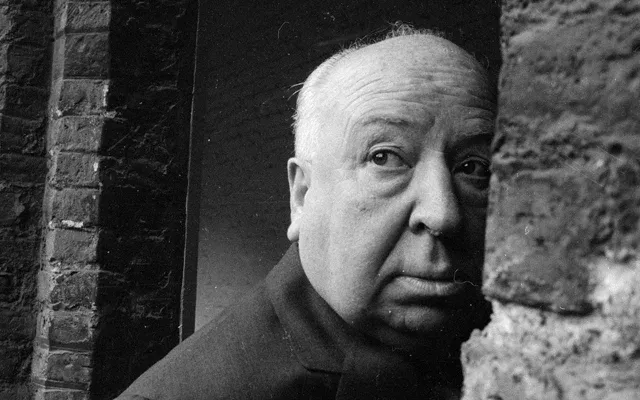

HITCHCOCK’S REAR WINDOW

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) raises all the right questions about Peeping Toms and voyeurism. Hitchcock himself once remarked to Francois Truffaut that Jeffries is “a real Peeping Tom... a snooper, but aren’t we all?” Are we indeed? Hitchcock’s biographer John Russell Taylor also quotes him as saying “a degree of voyeurism is only natural: the filmmaker’s art and the photographer’s are based on it.”

It would seem that if Hitchcock did not approve of Jeff’s occupation of photographer, then he did not approve of his own vocation as a film director either. He must have been aware of the pornography being shot by his peers. But he also could have been speaking about today’s TV cameras and mobile phones, which chase down tragedy in our communities in what can only be described as voyeuristic exercises. Media cameras are so often resented, not only by other cultures around the world, but also here in the West, and this means that the voyeurs have won, doesn’t it? Most citizens have become resigned to the media getting what they want, at somebody else’s expense.

In 1983, Rear Window was re-released in theaters (with Vertigo and three other Hitchcock films), and an academic tempest in a tea-cup erupted over Hitchcock and the nature of movie-going. It was asked, is Rear Window about voyeurism and do the movies cater to our guilty voyeuristic tendencies? Do we all secretly lust after our neighbors and our co-workers, and if we do, is that a bad thing? Here’s a poll some college film students took back then. Choose one:

- Rear Window and movie-going are both inherently voyeuristic.

- Rear Window is about voyeurism, but movie-going is not itself voyeuristic.

- Seeing is believing. Both are voyeuristic, but only to the degree that people believe them to be. As Hamlet once said: "there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so."

- Neither is really voyeuristic. Rear Window is just a movie!

Quite reasonably 50% of the students voted for #1 and 50% voted for #2. The agnostic option #3 was apparently too abstract. No one chose the cynical #4. Was this proof that we still live in a credulous rather than a cynical age? Or maybe it's just film students.

If Hitchcock had decided that human beings are naturally voyeurs and that filmmaking and film-going are both voyeuristic, then he also displayed a perverse fascination for the subject, meaning that he almost certainly counted himself among the guilty.

Other filmmakers over the years have agreed, and given it religious significance. Back in 1957, after Rear Window came out in France, directors Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol wrote: “We can never be hard enough on ourselves – such is [the film’s] lesson. Evil hides not only under the appearance of Good, but in our most casual and innocent acts, those we think have no ethical significance... This guilt which (Hitchcock) is so skillful in bringing to the surface is perhaps less of a moral than a metaphysical order. It is, as we have said... part of our very nature, the heritage of original sin.”

It is too easy to write this off to the naivety of an earlier age, or to the fact that French Nouvelle Vague filmmakers never had any fun. But it erupts periodically in contemporary America. Today there are many who would agree with those French directors and some of them are even film critics. Donald Spoto wrote in his book about Hitchcock: “the film exposes the ‘social contagion’ of a suspicious, prying view of others’ lives and the corruption of the ideal of neighborly love to which this leads.” Neighborly love? It’s not in any neighborhood I know. Nowadays one can find a horde of psychologists and psychoanalysts who will support Spoto’s thesis and argue that modern life is the story of the embattled self adrift in a world where there is no longer any privacy and that it is our own fault. Dr. Robert J. Benton wrote that Rear Window turns the mirror “back around to face the audience, and we realize that we are being shown our own manners and morals... Do we care, or is Mrs. Thorwald interesting to us only if she is murdered?” This is a dark view of modern life. Hitchcock’s human animal has been desensitized by life in the concrete jungle, by sterile architecture, by television and video games, and the only adventure left is spying upon one’s neighbors?

Not everyone is so pessimistic. Francois Truffaut also had a Catholic upbringing and it was apparently a lot worse than Alfred Hitchcock’s. Nevertheless, he could see the dark strain of masochism that pervaded Hitch’s films. Truffaut questioned why the activities in the film must be equivalent with Original Sin. Aren’t the characters indulging in curiosity, detective work, if you like? Even if one accepts the principle that it was voyeurism, haven’t most people learnt to respect the privacy of others? The critic Raymond Durgnat argued that “what badly needs privacy isn’t usually done before open windows... Would, one wonders, those morally fastidious film critics, if bedridden, really turn their backs to the window and refrain from speculating about their neighbors’ comings and goings… Far from seeing his voyeurism as sin, one may see it as also the beginning of involvement and intervention.” If Jeff and Lisa hadn’t spied on their neighbors, they would have failed in their obligations to them, which is a far greater sin, is it not? One of them could have been murdered before their very eyes and no one would have done anything about it? Hitchcock, it would seem, is arguing that this isn’t right and that one must get involved. A little voyeurism can be a good thing.

VOYEURISM

So are we all voyeurs? Once upon a time, the language of daily life joined the looker and the looked at in the same sphere: they were mutually dependent. Consider the word “look”: you can “look” at someone (observer) and “look” nice (be observed). One can “peep” through curtains into a larger space (active), and one can “peep” into view like a flower (passive), which is to say that it presents itself to be viewed. One can do the same for “vision” and “view.”

There are two things to say about this: (1) appearing in public means acknowledging that one can both look and be looked at. Circularity. That is a function of public life. But (2), and more importantly, these definitions are not loaded with any pathological meanings. How that has changed! Modern psychology has put a wall up in the landscape with the invention of the word “voyeurism” and the paraphernalia of psychotherapy and counseling. One cannot simultaneously look and be looked at when one is a voyeur. It is a one-way word. It requires setting up an opposite: “exhibitionism.” So now we have voyeurs and their victims, exhibitionists and their victims, in a process that turns ordinary human behavior into a disease and allows “experts” to intervene.

Consider the following dictionary definitions of voyeurism. Websters says: “(1) One whose sexual desire is concentrated upon seeing sex organs and sexual acts -- called also peeping Tom; (2) An unduly prying observer usually in search of sordid or scandalous sights.” American Heritage has “(1) A person who derives sexual gratification from observing the naked bodies or sexual acts of others, especially from a secret vantage point; (2) An obsessive observer of sordid or sensational subjects.”

These definitions were devised before erotic videos, DVDs and websites became widely available, so if one watches a porn website, does that make you a voyeur and what does that mean? Is it a bad thing? Apparently it is to all those who have set up websites and clinics to help wean people off “porn addiction.”

Then there are the English dictionaries, who can be counted on to be more authoritarian. The Oxford English writes: “A person whose sexual desires are stimulated or satisfied by covert observation of the sex organs or sexual activities of others; c.f. peeping Tom.” This definition then recommends we look up “scopophilia,” which is defined as “sexual stimulation or satisfaction from looking.” Since this is something we all do, then we are all scopophiliacs! The Encyclopedia Brittanica takes the same tack but adds: “Voyeurism is the reverse of exhibitionism and thus the complex is often called scopophilio-exhibitionism.”

Bruno Bettelheim, the psychoanalyst and writer, took aim at this monstrosity, seeing it as a horrible distortion of Freud’s writings. In his book, Freud and Man’s Soul (1982), Bettelheim argued that Freud himself had a relatively narrow definition for voyeurism. In Three Essays on Sexuality (1905), voyeurism was a “perversion” away from the all-important act of sexual intercourse onto some substitute activity. This is the basis for the Encyclopedia Brittanica definition cited above. But Freud also acknowledged the sexual pleasure to be gained from the ordinary, everyday looking that we do in the word “schaulust.” Bettelheim pointed out that Strachey, Freud’s English-language translator, did us all a disservice by translating this into the faux-Greek word “scopophilia,” (scopy = look, philia = liking; i.e. to like to look). It has more than a passing resemblance to hemaphilia, pedophilia, necrophilia, and coprophilia. No longer is it something we all do; it is now something we know we shouldn’t do.

But no one is listening to Bettelheim. According to the dictionary definitions, looking at something sexually stimulating (streaming video, websites) and taking pleasure from it is actually a sickness, a disease, an addiction, and there appear to be many people who subscribe to this viewpoint. It is equally true to say that there are even more people who are torn between their desire to watch and their fears about what that says about them.

PRIVACY VERSUS PROPERTY

Rear Window is not even about voyeurism really. Nor is the story of Lady Godiva. They are about the eternal conflict between the right to property and the right to privacy. When Jeff and Lisa looked out Jeff’s window and thought they saw a murder, they were exercising their right to do so, a right founded on the right to property. When critics try to draw a line between this and being looked at, they are, quite rightly, advocating the right to privacy. But the two are fundamentally irreconcilable since the line between them is drawn according to personal preferences, as much as social or legal ones.

For example, if Jeff thinks he sees a murder and he screws a telephoto lens on to his camera, has he stepped past his right to property and violated the other apartment dwellers’ right to privacy? Remember he was motivated by worthy ideals; he was concerned that a woman had been murdered. Her curtains were not pulled; hadn’t she (or her husband) waived their right to privacy in this case? Furthermore, isn’t it a social obligation to protect a woman from spousal abuse?

If the right to privacy is often at odds with the right to property, property authorizes the gaze while privacy refuses it. To own a painting, a house, a lover, gives you the right to enjoy it, gaze at it, display it, imitate it and be unrestrained about it. It may be an illicit pleasure, such as the painting of a nude on the wall of a great mansion, or a porn website. It is property that allows you to define your private self in terms of what gives you pleasure from looking at it. To have no property to look at means you do not need privacy since there is nothing to protect, nothing physical to take pleasure from. This is not an argument for collecting excessive amounts of property; that produces the sense of privacy that is often called paranoia. Neither is it an argument for doing without property, for those who believe that the privacy of one’s own mind is sufficient are deceiving themselves about what it means to be homeless, lost or abandoned. Above all, privacy is a state of mind mutually interdependent with property.

The mind may be the hardest thing for one human being to deprive another of. You must drive them mad first and the surest way to do this is to strip away all sense of property. But even a supermarket cart can contain a kingdom. Alternatively, you may be able to achieve the same effect by walling someone off inside their own property. You can count on many extremely rich people being among the loneliest on the planet.

Many have argued that the function of myth is to resolve conflicts between irreconcilable opposites in our dualistic universe. In Rear Window, where the right to privacy and the right to property collide, there is no resolution really. The film allows you the opportunity to decide for yourself – if it is about voyeurism, then that is how you see it. If it isn’t, then it isn’t. Seeing is believing.

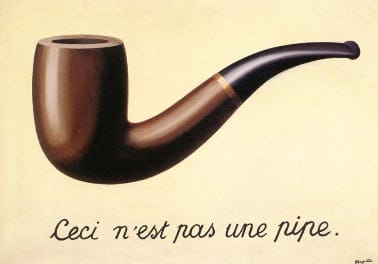

In Muslim societies, representations of God are not permitted. In the West, this is often dismissed as a sign of naivety. After all, Jesus iconography is pretty much able to go anywhere nowadays. But the Muslim prohibition is rarely understood for what it is – a sophisticated view that argues that representation drives out meaning, especially spiritual meaning. It's like reading a great book and then seeing the movie version and realizing it's nothing like your memories.

Could it be that in the West a profusion of messages ends up producing clutter and noise, diminishing the value of everything (“Quantity drives out quality”?). In Muslim societies, they understand that to represent God and the Prophet is to debase them. Such a belief relies upon a strong sense of dignity and privacy that is significantly under-valued, indeed deliberately eroded, in the West. Many Muslims have a horror of the West’s consumerism, seeing in it a self-destructive urge that they want no part of. It is a perfectly valid criticism. Curiously, this is something that Christian fundamentalists have discovered too, which is why some insist on going back to basics, as it were, to focus on core spiritual values rather than succumb to the distractions of a consumer society (i.e. property). They have a lot in common.

Modern Western consumer societies are based on the increasingly rapid circulation of people in urban spaces (just as they are based on the circulation of capital flows and ideas on the internet). Community and neighborhood are becoming less important, having been replaced initially by the completely different concepts of the mall and the theme park. Surveillance cameras popped up everywhere in public spaces ("Hi, you are being recorded..."), just as webcams are are now ubiquitous at home, on cell phones and in porn and social media is everywhere. Baseball and football stadiums, which once unified communities, are becoming less personally engaging for fans, being replaced by television broadcasts into the home, obliging sports teams to get into the business of showbiz to keep up attendance. The result is increasingly impersonal. Some even equate this with dehumanization and alienation. The increased circulation of people in modern societies, both in real space and in electronic space, has weakened the sense of self among many citizens and increased the sense of violation that they feel. This is nothing new really, for modern society has had to grapple with how to protect privacy just as other societies have had to do in the past. But no wonder the rich want to go and buy private islands somewhere, why the upper middle class aspire to gated communities and the middle and working classes have taken up pornography and social media. It’s all about escapism and the term voyeurism has emerged as part of the lexicon.

Fortunately you don’t hear as much about scopophilia and voyeurism these days, but it hasn’t really gone away. For the question remains: why do so many people embrace pseudo-scientific words like these? Are they a panacea? In our world today, irreverent and rebellious behavior is often (mis)diagnosed as ADHD, ED and Autism, medication is prescribed to do away with annoying children, and “child abuse” by the Church, by teachers, by parents or by a relative is treated with such hysteria that the child is stripped of all defenses and forcibly compelled to play – and become – a victim, thus confirming the nightmare. We risk a great deal when we allow the experts in psychology, psychiatry, pediatrics, education and the media to “explain” things for us and make decisions for us that result in punishment when there are alternatives available. They - and their Inquisition bible the DSM - are our pathologists of gloom, the ones who want to blind Peeping Tom. Words like voyeurism create prisons in the mind and the best way to destroy those prisons is to refuse to accept their validity, as Lady Godiva did when she flouted convention. The most powerful idea is not the idea whose time has come but the idea that everything in the end is just an idea.