Life as Opera

From Lola Montez to Mata Hari

Lola Montez and Richard Wagner

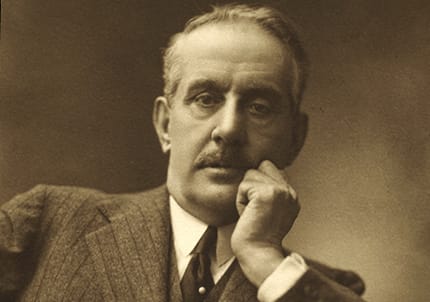

Once upon a time, in Starnberg near Munich, Richard Wagner was working on pre-production for his groundbreaking new opera Tristan and Isolde. The year was 1865. Across Europe, in Paris, Georges Bizet was on a train to the nearby village of Le Vésinet. Unlike Bizet, Wagner was feeling very self-satisfied. His moody opera had been completed five years earlier and still it had not been performed anywhere, but at last an invitation had arrived, from King Ludwig II of Bavaria – Ludwig was a huge Wagner fan – summoning him to Munich to mount the kind of extravaganza that Wagner always intended for this opera.

Wagner was single again; his wife had left him for good this time. Life now was to be lived in a state of perpetual crisis. He was broke, of course, and he knew he was not welcome in most of the great cities of Europe. But things were looking up. As he prepared the opera for rehearsals, he recalled how the adventuress Lola Montez had careened around Europe 20 years earlier, before she too had settled in Bavaria. Lola often crept into his thoughts these days. She was only four years in the grave and the strange connection between them haunted him. Wagner was well on his way to becoming the celebrated composer whose music would dominate the late 19th century world, while Lola Montez never would be heard of again. But there had been strong and ironic resemblances between them.

Their careers had been launched at the same time –Wagner’s with a successful performance of Rienzi in Dresden in 1842 and Lola’s with a Spanish routine during intermission in The Barber of Seville on the London stage in 1843. As they both became better known, they moved in the same fashionable crowd and Wagner began monitoring Lola’s progress. Inevitably, they collided one day in Dresden, whereupon he sized up his doppelganger. Lola was in the company of Franz Liszt – we only have her word for it – after a series of whirlwind marriages and affairs in India, London, Paris, Warsaw and St. Petersburg. She hardly noticed Wagner of course and he resented it. The genteel set seemed entertained by Lola, who had so little respect for the niceties of polite society – a cynicism she kept all her life, even as she enjoyed its decadence. Wagner knew she was never really accepted by them; dancers were forever on the borderline. But it seemed to make no difference! She was uniformly roasted in the press (when they weren’t being paid off) and audiences booed and hissed most places she went, yet this did not dent her ability to draw a crowd. Far from it, for her appeal lay in the “tease” whereby the audience was incited to participate and react, in the venerable tradition of music hall and pantomime. Frequently she became the main draw!

Wagner found this irritating. Her kitsch dance routines with the castanets and fans and extravagant costumes were the embodiment of everything that was wrong with contemporary opera. She was a lower-class tramp with a mean temper, and though she wore great clothes (something he appreciated), he could not understand her popularity. He had not been surprised when Liszt dumped her in Paris. Perversely though, after an initial fiasco, Lola had been embraced enthusiastically by the Parisians and she stayed on to enjoy it. Wagner was envious. Paris was the most fashionable place to be and being popular there meant something. But after a duel resulted in the death of her lover, she was obliged to leave Paris in a hurry, and so she had come to Bavaria. A story not unlike Wagner’s as he fled from his creditors, one city after another.

Lola first imposed herself upon the good citizens of Munich in October of 1846. There is a famous legend of how she first met the King, Ludwig I (Ludwig II’s predecessor and grandfather). She sought out the cafe in town where Ludwig’s chief adviser took his coffee in the morning and contrived to fall off her rented horse at his startled feet. Of course he sprang gallantly to the lady’s assistance, and it wasn’t long before he was promising her an audience with the King. When the big day arrived, Lola overheard Ludwig in the next room trying to get out of the meeting so she raced past the two guards and strode in front of the 60-year-old Ludwig. The story varies a bit at this point. Some say that as she was standing in front of Ludwig he asked “Nature or art?” a question that could well be asked of many of today’s celebrities. She took up a stiletto letter opener from Ludwig’s desk and cut her blouse open to prove there was no padding. Perhaps she had the stiletto in her clothes for just this very moment? Others report that as the guards wrestled with her, her dress was torn off the shoulder and that she ripped the other shoulder off for good measure, baring her full breasts before his royal gaze. At any rate Ludwig was impressed.

No surprise then that within the year Lola was running the government of Bavaria, or at least ordering it around. But, true to form, she also went out of her way to cause offense. One could argue that the Bavarians needed a shake-up, but it also seems evident that Bavaria’s conservatism provoked Lola to new excesses. In the end it was the nationality issue that became her downfall: she manipulated Ludwig into granting her Bavarian nationality, the titles of Countess of Landsfeld, Baroness von Rosenthal, Canoness of the Order of St. Therese, her own villa, and 20,000 florins a year – all at taxpayers’ expense. Her enemies complained bitterly, “National feeling is wounded; Bavaria believes itself to be governed by a foreign woman, whose reputation is branded in public opinion.” With all of Europe already in an uproar – this was 1848, the year of revolutions – the king unwisely dismissed his government. Things went from bad to worse and the college students did what students do best – they protested and then rioted. The king revoked his naturalization order and Lola was forced to flee across the border, disguised as a boy. Ludwig was not able to hold on to his throne, but the citizens felt that they could forgive the old man his follies.

The top 10 performers in North America, according to Opera America are:

Madame Butterfly

La Bohème

La Traviata

Carmen

The Barber of Seville

The Marriage of Figaro

Don Giovanni

Tosca

Rigoletto

The Magic Flute

Tristan and Isolde

For Wagner, Tristan and Isolde would represent everything that Lola Montez was not. The opera would continue a theme he had been working on in the earlier Tannhäuser and Lohengrin – the search for the perfect woman, the ideal soulmate. It was a worthy theme that had interested intellectual men through the centuries. For Wagner, as with Beethoven and Goethe, it had real-life implications: it turned on the question of how he should behave with women whom he adored physically and spiritually but who were married to other men. In other words these were women he could not, or should not, have.

Perhaps for this reason, Wagner was drawn to the story of Tristan, Isolde and King Mark, the tragedy of a love triangle gone bad. Wagner by 1865 was himself in just such a triangular relationship with Mr. and Mrs. Von Bülow – Hans von Bülow was his conductor but it was the wife Cosima von Bülow who was spending most of her time with him. (She asked her husband for a divorce in 1868 and he eventually granted it. It was finalized in 1870, by which time Wagner and Cosima already had three children together. They married later that year.)

It seems the inspiration needed to compose Tristan and Isolde had come earlier, from his time spent in Zürich and Venice in 1858-59 in the company of the magnificent Mathilde Wesendonck. It seems equally likely Wagner never slept with Mathilde, who was married, but she apparently called forth in him that hopeless passion and exquisite torture that comes from experiencing Tristan and Isolde. It is the ever-shifting distance between desire and denial – the woman one desires yet who is faithful to someone else. This tension (influenced by reading Schopenhauer) afforded a glimpse of what Wagner took to be nothing short of the meaning of life, whether one called it the infinite or immortality or oblivion or death (liebestod). For Wagner, opera could focus us on that feeling. It inspired a sense of surrender to what sometimes can turn into overwhelmingly powerful passions. If the opera fan could not feel those desires, then the more pity them. Wagner felt that through music one could achieve a virtual disintegration of the self. One could experience rapture, transcendence, orgasm and then peace of mind, something many music critics feel he comes closest to in Tristan and Isolde’s second act duets and its finale. By that time, Isolde has dropped dead over Tristan’s body. It’s not for everyone.

How ironic then that Wagner’s most adoring fan – the young King Ludwig II -- loved Wagner and his operas with a lusty passion that mocks Wagner’s lofty pretensions. Ludwig was almost certainly homosexual and the snottier courtiers had Wagner picked out as one of Ludwig’s boys, earning him the nickname “Lolotte,” a reference to Lola. The legends abound, and it seems that Ludwig on occasion enjoyed himself recreating the erotic Venusberg scenes from Tannhäuser at the court. Another time, Wagner caught Ludwig parading around the palace with the Swan Knights of Tannhäuser and on one particularly ugly day, Wagner had found him dressed up to resemble Lola Montez. Whether this was to tease the courtiers and bureaucrats or to tease Wagner, or whether Ludwig was simply making an ironic commentary upon a celebrated moment in Bavarian history, he did not know. At the present time Ludwig was enthusiastically suggesting that he cast himself as Isolde with Wagner as Tristan, for horsing around the castle. How many other composers had this problem with their patron Wagner wondered? Certainly he knew Voltaire had had to keep the young Frederick (the Great) at beyond arm’s length. Unfortunately Wagner’s own flamboyant taste in rich colors, silks, furs and perfumes didn’t help. One of his nastier critics would perceive an aura of homosexuality vibrating throughout the music of his operas. What could you do with critics like this?

At the end of 1865, Tristan and Isolde was performed successfully in Munich and Wagner felt vindicated. Yet, true to form, he was fleeing Bavaria within months, all good will used up and deeply in debt once again. The irony here is that Wagner was repeating the flight of Lola Montez in 1848, running away from a Ludwig. Damned if he would dress up as a girl though.

For Wagner, the highest state one might aspire to with Lola Montez was being eaten alive by her, which had its merits. Yet they were really little different from each other – both were impetuous and arrogant, reckless spenders and restless spirits at heart. Lola had been a rival for the world’s attention in the worst possible way. While music critics have lambasted Wagner’s extravagance and his ego, fewer have acknowledged his ability to cultivate his public image, just as Lola did, and for a decade she had been better at it and, as a result, more famous. Word of her death in New York had reached Europe quickly – a true measure of her cultural impact perhaps? Wagner considered her the most vulgar spirit of the age in which he now found himself. There was something so…American…about her. How appropriate she go and live there. Lola had been a burlesque of womanhood, a painted and jeweled harpy who was all facade and no substance. Her body, her physicality, her lusty desires, her narcissism had been the very opposite of the ethical and spiritual values he felt people should aspire to. Indeed Europe seemed to be turning into everything tawdry that Lola had stood for. Of course Wagner’s impact on late 19th century music would be enormous and Lola’s ultimate impact on contemporary culture would be minimal, yet at the time she was an equally valid symbol of where 19th century European culture was headed…

Carmen

Back in 1865, Georges Bizet was on a train from Paris to the outlying village of Le Vésinet where his father had bought some property. On the train he met a woman who had an edge on him when it came to being somewhat famous. Her nickname and stage name was la Mogador and she too had bought land near the village – and so they would become neighbors. In the years since then, the village has been absorbed into the Paris suburbs but this was once a quiet place where dancer Josephine Baker made her home and just across the Seine in Louveciennes is where Anaïs Nin made her home.

The woman on the train, Céleste Mogador, is one of those marvelous colorful figures who bursts out of the Bizet biographies, proving more interesting than the composer himself. She was 41 while Bizet was 27, but she could still catch the attention of men with her looks. She was “wasp-waisted, supple as a willow, lively as a linnet… just pock-marked enough to suggest a slight resemblance to the Venus de Milo,” wrote one contemporary. Was she the inspiration for the music of Bizet’s Carmen? Certainly Mina Curtiss, Bizet’s principal biographer, thought she was.

Born Céleste Vénard in a working class Paris suburb in 1824, she had run away from home at the age of 13 to get away from the attentions of her mother’s lovers. Able to survive only as a prostitute, by the age of 16 she was ensconced in a bordello where she entertained the by-then dissolute poet-lover Alfred de Musset as a client. Too ambitious and proud for the bordello, she quit after de Musset took her on a date to a restaurant and sprayed a bottle of seltzer water all over her for his amusement. She decided to be a dancer instead, at almost the same time Lola Montez made that same decision. There were few other ways a gal could aspire in that social system.

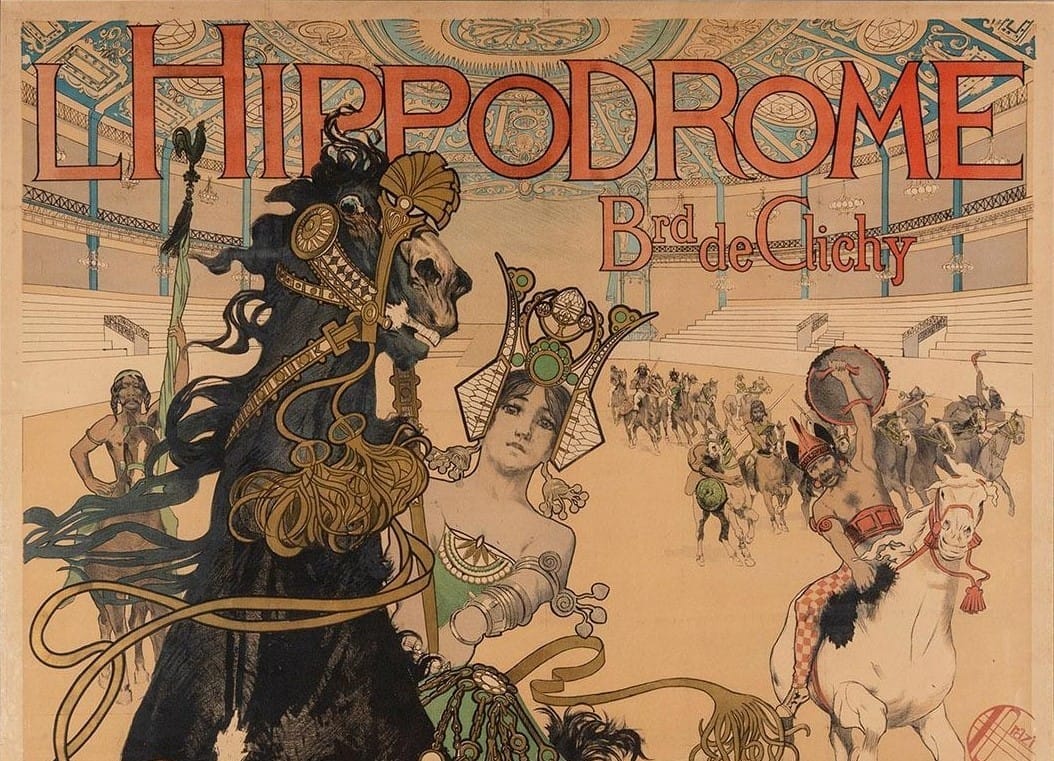

It was while entertaining clients in the ballroom that she gained her nickname, after the Moroccan city that the French Navy had shelled recently. Of Céleste’s virtue it was said, “It would be easier to defend Mogador.” Moving on from the ballroom, she became famous as a circus rider at the Paris Hippodrome, admired for her acrobatic stunts, before she successfully snared an aristocratic husband. His family was horrified; after all Céleste was still registered as a prostitute. Her husband remedied that blot on her character by filling out the requisite paperwork, but then proceeded to go through her finances as well as his own and she was obliged to write her memoirs to help pay the bills. Those memoirs were suitably scandalous and they sold very well (“Like Jean-Jacques Rousseau,” declared the supportive Dumas père). But her husband fled to Australia where he assumed the post of French ambassador. La Mogador sailed to visit him and it is curious to think of her in Australia around the same time as Lola Montez. Her husband died in 1858, and after that Céleste took up an interest in the opera, going on to write and produce a series of operettas as well as novels, plays, songs, poems. The Bizet biographer dismisses her as “a poor man’s George Sand,” but this is elitist snobbery. Financial success came when she staged a version of her novel The Gold Robbers (Dumas père did the transcription), and it became a smash hit among working class audiences. She was able to buy the property at Le Vésinet with the proceeds and this is how she came to meet Bizet and inspire him. When he composed Carmen some years later they had long gone their separate ways, but who is to say whether she was the inspiration for Carmen?

The original Carmen story was written by Prosper Mérimée, who had long been interested in Spain – as well as in the south of France and the Gypsies. The women were so exotic by contrast with Paris and that mattered to Mérimée, who was a ladies man. He claimed first to have heard the story on a visit to Spain in 1830 from the Countess of Montijo, who would become his lifelong friend. He also admired and wrote about Cervantes, whose novela La Gitanilla (The Gypsy Girl) features a beautiful heroine named Preciosa. But the fact that Carmen wasn’t published till 1843 when Lola was making out like Carmen may have accelerated his desire to get the story published. He has a great line for Carmen: “Women are like cats; they don’t come when you call them and do come when you don’t.” His Carmen, like Lola, used her body in public as a sexual weapon, flaunting it, knowing that men were drawn to it and she indulged in stormy love affairs.

A generation later, what would appeal to Bizet about such women was their feminine physicality and vitality, their energy, their strength, their being true to themselves, and this appears in his operatic heroines l’Arlésienne, Djamileh (based on a de Musset poem) and Carmen. Wasn’t that what opera was all about anyway, not Wagnerian slow death by oblivion? In Bizet’s own life he was not so lucky. Carmen was first performed in 1875 and he would be dead within the year at the early age of 36, from a failed heart and depressed that his marvelous opera had not succeeded as he had hoped.

In critical terms, Bizet helped begin the “verismo” style of opera, “realistic” in its portrayal of the seedier side of life. He wanted a sense of naturalism to his opera, where the stage served as a public space for examining and even sanctioning immoral behavior, at least by governing class standards, so his factory girls smoke cigarettes on stage, and his heroine stabs another cigarette girl to death. Depending on whom you read, this can be the story of an honorable soldier who falls apart while Carmen remains both moral and subtle, always honest with herself, refusing to follow bourgeois sexual codes. She knows her sexual powers and how to use them, but she isn’t promiscuous. But then there are those critics who discern a coldness and a contempt for men, as well as blatant, unsubtle sexual display. That kind of criticism has not gone away since the opera opened, upsetting Paris opera-goers, when the critics called Carmen a harlot and the hero Don José vile and odious. They could have been talking about Lola Montez, word for word… or today’s teenagers for that matter.

Carmen was as revolutionary in its own way as Wagner’s early operas had been. But Wagner could not have made an opera out of Lola Montez, for she was a survivor, a cat o’ nine lives, even if she died at the young age of 39, whereas Wagner’s lover-heroes had to die an ennobling tragic death at half that age. But a French composer undoubtedly could work lust into his musical score. If Wagner could have the royal Tristan and Isolde killed off by other royals, Bizet could have his definitely non-royal heroine killed by her equally non-royal lover in a steamy and stormy emotional climax.

Curiously, Bizet found his music constantly being described by the press as “Wagnerian” and it was the Germans, from Brahms to Bismarck, who embraced his music far more enthusiastically than his fellow Parisians did. Perhaps it was all that Mediterranean sunlight in Carmen that the Germans responded to? Perhaps it was a clever act of musical colonization? Wagner actively promoted national unity and pride with chilly northern myths because they possessed neither unity nor pride themselves – something Bismarck was able to exploit. Wagner himself was on the barricades in Dresden in 1848 and, in the subsequent years, though his operas and his writings primarily appealed to the avant-garde rather than the streets, they played a role in unifying Germany. His music seemed as muscular and as inevitable as Prussian armies as they rolled across Europe. The French, on the other hand, looked abroad and southwards because they already had more than enough unity and pride. Indeed they had an empire to maintain. But they reeled from one political crisis to another.

There is something else here though: why did Wagner never make women the central characters while French composers took the opposite tack? Indeed, the essential difference is that Wagner’s operas celebrated dying heroes while French and Italian opera celebrated dying heroines. Wagner’s characters seem doomed by Fate in the same way that the others are doomed by debilitating diseases like consumption. Not in Bizet’s operas. His heroes and heroines are agents of their own downfall and they know they are responsible for their own actions.

This invites a question: does it mean anything? Nietzsche thought so. After initially embracing Wagner’s music, from 1878 onwards he turned against him, damning Wagner’s Teutonic myths and Scandinavian monsters, seeing in them everything he found sick and decadent about European culture and German culture in particular. Nietzsche wrote that “music is a woman” and that Wagner’s sensuousness made “the spirit weary and worn-out. Music as Circe.” It is music that makes you “sweat”; it “is evil, subtly fatalistic.” Is there a whiff here of what would come – the descent into the horrors of World War I and World War II – or is he over-reaching? (How ironic then that Wagner had been busy blaming the ruination of music, and much else, on the Jews - in the infamous essay Das Judenthum in der Musik, written in 1850 but widely available from 1869.)

Nietzsche liked Bizet though, as did Tchaikovsky. It wasn’t important that Carmen dies at the end; that was merely a dramatic convenience in a century when somebody had to die in order to produce heartrending arias. What was important in Carmen was that there was no imminent betrayal by Fate, as there is in Wagner, or by the body as there is in, for example, La Traviata. Disease stalked Bizet and his wife, as well as Chopin, Nietzsche and others in this chapter; it also stalked the body politic of France, Italy and Spain throughout the century as they suffered one indignity after another. For Nietzsche, the triumph of Carmen was that it transcended all that with its physicality and, simultaneously, its lightness of touch. Carmen, like Lola and la Mogador, evoked the warm sun and rich colors of Spain, the passions of the Mediterranean world, the Gypsy life, the triumph of the body over death – the very opposite of everything Wagner’s operas stood for and everything Nietzsche was afraid of. Freed of these physical limitations, women like Carmen, Lola and la Mogador appeared to have free agency, long before the era of women’s suffrage. It also didn’t hurt that they were their own best publicists. They could wear Oriental turbans and slippers (a la The Arabian Nights) and Spanish costumes (a la Carmen) if they felt like it. They could stage dramatic scenes and romance their lovers as George Sand did for Mérimée, as Lola did for her lovers, as Wagner did every day of his life, as Madame de Stael did by shocking people with her costumes and her cleavage. Others assumed men’s costumes and exotic foreign costumes at a time when European imperialism was spreading over the globe. These were acts of sabotage -- the work of cultural vulgarians. It was as if life and art were one, as if life were an opera. This fascinated the European public and so these women became celebrities, inspiring women outside the opera house in the real world.

Manon

The femme fatale who emerged in the Europe of the 1880’s appears in the Jules Massenet opera Manon (1884) and the Puccini version Manon Lescaut (1893). Manon herself was the creation of Abbé Prévost back in 1731, a working class girl whose looks dazzled the men and who wanted to make her own way in society as Lola and la Mogador would do. Massenet himself had a happy and a successful lifelong marriage to his wife, Ninon, and despite the rumors to the contrary, he may well have been faithful to her. But as he well knew, the public’s appetite was not for faithful husbands and wives but for Eve, Mary Magdalene, Salomé and Sappho. Give them what they want, he thought.

It is the age-old conflict between the courtesan and the priest, between voyeurism and guilt, that drives the plot of the best operas, including Manon, which is about how a voluptuous young woman brings an earnest young man to grief. It begins as a tale of young love: a coquette and a naif who wants to become an abbé. She seduces him and spends all his money, they part, they are reunited, and there is an obligatory tragic ending. Massenet was accused of setting a French story to German music (they meant Wagner again), but in fact it was the attempt to capture Manon’s eroticism in music that most attracted and challenged him. Eroticism in music was new and exciting, just as it was in painting and sculpture, and there was definitely something electric in the air during the 1880’s.

Civilization survived the Gay Nineties as the late Victorians gave way to the Edwardians and France was wracked by the Dreyfus trial and the Catholic Church was in full retreat. Just to stay fashionable one had to be androgyne or bisexual, a sadist or a masochist, a lesbian or an invert, or even a transsexual or hermaphrodite. This was the heyday of the Folies Bergère and the Moulin Rouge, Mistinguett, La Goulue and Jane Avril, Oscar Wilde, H.G. Wells and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Octave Mirbeau, André Gide, Paul Valéry, Anatole France and Claude Debussy. Helena Rubinstein, Elizabeth Arden and Madam C. J. Walker took make-up out of the theater and launched their cosmetics lines for respectable women. Lesbians were fashionable -- the American Natalie Clifford Barney, “the wild girl from Cincinnati,” was host of the “Amazons” salon, a mostly lesbian avant-garde group of artists. Then there was Sigmund Freud’s friend, Lou Andreas-Salomé who, apparently, never consummated her marriage in all those years and, of course, Freud’s psychology was as much as anything an attempt to explain what all this sexual confusion was really about.

Manhood itself was in danger, some said, from radical women. Many of them were even demanding a vote! The way had been opened for women to aspire to ecstasy, to express themselves freely, to switch between the traditional roles of mother, sister, mistress, wife. It meant trouble and the opera house was the perfect place to do it in, with actresses and singers taking the lead. On stage they expressed heightened emotions and violent passions and they were sanctioned to do it. As they were performers, they were not playing themselves but fictional characters. On stage, as they say, anything goes. Of course, the private self had to be held to a higher standard of integrity. Oscar Wilde failed to understand this and ended up in jail. There would be others who would meet an even worse fate.

Salome

On October 15, 1917, Mata Hari was executed by firing squad on the grounds of the Château de Vincennes, on the eastern outskirts of Paris, after being convicted of espionage for Germany. It was said that when she was arrested, she welcomed the police officers stark naked and invited them all into bed with her. It was said that she went bravely, refusing the blindfold and standing perfectly still. It was no doubt a traumatic experience for her young firing squad, since she was staring straight back at them. Arrayed in the latest creations of the Paris fashion world, as the guns fired, she collapsed in a heap of petticoats. One soldier was said to have remarked, “There is one who knows how to die.” Execution as the ultimate performance.

It may not all be true, but of such material legends are born. Mata may have been in on a plan to load the guns with blanks but real bullets were substituted at the last minute, an act of treachery straight out of Tosca. Others say she blew a kiss to her executioners, a last act of bravura, while still others say that just as the guns were about to fire, she ripped away her blouse and displayed her breasts for her executioners (something she never did during her dancing career). Maybe they would have had to pause, check the breasts, and mentally ask whether they didn’t look too bad for a woman of 40 something. OK, that last bit is made up, but the legends are hilarious.

The oddities did not end there. Because no one would claim the body of a spy for fear of being arrested themselves, it was donated to science and who knows what the medical students at the University of Paris thought of it as they picked their way through the remains of the vital organs shattered by a hail of bullets.

These legends enraged Natalie Clifford Barney, who became determined to get to the bottom of it. She tracked down the commander of the firing squad and discovered that almost none of it was true, other than Mata Hari had gone out with style and with pride. Barney had been one of the first to invite Mata to dance and perhaps it was because she was a foreigner that she quickly understood what a travesty the trial and execution were. Certainly no one else was prepared to contradict the panic and paranoia spreading at the time. Everybody sweated.

Those views of Mata Hari persisted well into the 1970s, when she was still considered a German spy by many in France. She was a major celebrity when she died, but she had suffered through tough times to get to where she was.

Born Margaretha Zelle in 1876 in Leeuwarden in the Netherlands, she was married in 1895, had a son in 1897 and a daughter in 1898 while living in Java (then a Dutch colony), lost her son in 1899 and was divorced from her abusive husband in 1904. “Mata Hari” was created in 1905 out of necessity. She had to survive and Paris seemed the place to do it in. Her frank sensuality and her apparently terrific body were perfect for a dancer. The name she chose, Mata Hari, meant “Eye of the Sun” or “Eye of the Morning” in Malay. When she danced she would evoke the sacred rituals of Javanese temples and she called herself the sacred courtesan of Shiva, god of destruction. If her geography was a bit mixed up, she did seem to know all the sex manuals of Asia. In her private life it was said she stripped naked and danced with a snake for her most intimate lovers in an amorous intoxication. She aimed to express the mysterious Sphinx-like side of femininity -- sexy but dangerous – in whatever operatic setting would draw an audience.

The French writer Colette thought she was “a transparent fraud” but conceded that Mata knew how to use her body for maximum sexual effect. Others from the smart set – those around Diaghilev for example – were much more critical, patronizing her as really not that beautiful, vulgar even, with no personality. Just as Lola Montez had been dismissed, so too Mata Hari was never fully accepted by the High Art crowd, indicating that class played a major role in all this. Even today, feminist writers dismiss her, opening themselves up to charges of elitism. But back then, Mata Hari’s working class physicality and sensuousness may have enhanced her erotic appeal to the idle rich and to others who appreciated that she was different from the other dancers. Beauty is, after all, in the eye of the beholder.

It was with the act of striptease, exoticized and glamorized, that Mata Hari made her name, especially her rendition of Salomé’s Dance of the Seven Veils. The act of striptease and dancing naked were symbolic of the new century, an aggressive throwing off of all restraint. It matched the late imperial mood in Europe, which had forcibly colonized most of the globe and now was in the mood to explore erotic conquest as well. Sexually provocative dancing, especially the striptease, was perceived as being more than merely bourgeois male sexual fantasies; it was defended as avant-garde art. It could be mercenary and confrontational, or it could also be subtle and self-creative. Either way, it was exclusively the bourgeois rich who got to see it, who claimed it as a new art form in order to distinguish it from its working class and libertine equivalents. The cynic would say that if a woman took her clothes off in a private showing, one could always call it ART by pretending that it revealed a woman’s feminine self to the male or female voyeur just as a great painting like Mona Lisa might reveal her spiritual side, but in a sense the striptease did reveal something. Rich men and women could inhale the feminine self, as it was revealed, and this was liberating to a generation of men and women who did not undress before their own wives or husbands. The exotic foreign quality was a bonus.

The great dancers and strippers made up the stories of their lives and it was almost as if those layers of personality were coming off too, along with the soon-to-be-abandoned corsets. That was the essential appeal of Lola Montez, la Mogador and Mata Hari: it wasn’t just the erotic charge of the physical striptease but that these women were genuinely interesting to their audiences. Who were they really? What did they want in life? Were they all they were cracked up to be? How did they have the nerve to throw off all restraint? The striptease was not just a metaphor for what any performer was supposed to do on a stage – reveal character – it was also a metaphor for the stripping of illusions and excess psychological and religious baggage that marked this era.

The striptease supplanted opera as avant-garde art and voyeurism remained a relatively private affair and is so even today. It has been public only to the degree that the performers know their act is for others’ private consumption. Yet the need to be seen, to be viewed as an object of sexual desire is still what drives the striptease – it is essentially a performance. Over the years acting and dancing have become more publicly erotic. The need for eroticism is grounded in the reality of our lives, by the increasing separation between private housing and public streets, by the fact that true privacy is confined to the bedroom or wherever the laptop or phone is, and by the decrease in daily physical intimacy. Striptease provides a window on the private passions, a mirror for those who can experience it personally and a release for those who cannot. It is not true to say that this always involves men watching women. It is also untrue to say that erotic voyeurism is a one-way transaction. In the striptease, the looker may be at the mercy of the looked at, and a reversal is possible, where the woman can intimidate the man, where the man can perform for the woman or another man or a woman for another woman as Mata Hari did at Natalie Barney’s.

So was Mata Hari a spy? The biographers are divided. Clearly there was not enough evidence in the dossiers to have convicted her and those disposed to a guilty verdict only felt that way because they knew she consorted with powerful military and political figures in France, Germany and elsewhere, so how could she have been otherwise? They reasoned that she must have traded in secrets as she traded in sexual favors – pillow talk. Others dismiss those “secrets” as gossip that anyone could have picked up in the cafes and it was anything but secret. The war was going badly for France and scapegoats were needed, preferably foreigners, and she was known to hang around with German diplomats and military officers and that made her a target. On the other hand, there may be evidence to support the charges she was German agent H21. Either way, the French government, the public and press were in a race to the bottom. Paranoia was widespread and “spies” were spotted everywhere, as indeed they were elsewhere in Europe. The old order was dying and with it Mata Hari’s world. Whether she was a spy or not, she must have resented the fundamental unfairness, the transparent rigging of the trial by a hypocritical and failed regime. Once she knew she was going to die, she went with dignity. This bears a striking resemblance to another famous execution. Was it just a coincidence that within three years, Joan of Arc became the patron saint of France? She too had been put on trial and executed for dubious reasons. Is there much difference then between treason and heresy?

The striptease is a metaphor, if ever there were one, for the rot occurring in the traditional stabilizing belief systems at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th. Christianity, Islam, Imperialism and Family Values were being radically undermined. This is reflected in the transition from the adventuress living her life in public, in the opera house, to her darker figure, the femme fatale, who was a much more private and shadowy figure. Her frank sensuousness may have been in tune with European High Culture, with its thrill-seeking and its mix of cynicism and sentimentality. But when World War I came, Mata Hari failed to grasp that the forces of darkness were closing in on her, just as Oscar Wilde had failed to recognize similar signs back in 1895. When she was arrested as a German spy, and then shot, the adventuress had become a martyr. But was she the end of something from the 19th century or the beginning of a new legend for the 20th? And what would happen to the opera after Mata Hari’s death?

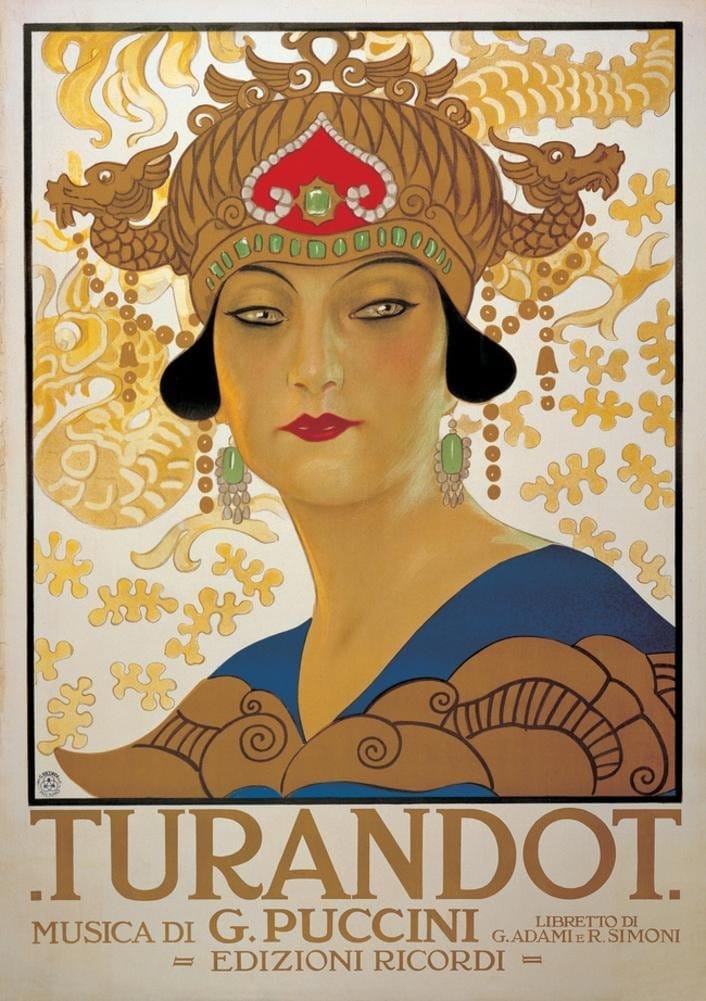

Turandot

In Viareggio, Italy, Giacomo Puccini had his own Mata Hari weighing on his conscience. Back in 1909, Puccini’s insanely jealous wife, Elvira, had accused him of an affair with her maid, Doria Manfredi, and mounted a nasty campaign of slander and lies against Puccini and Doria that went on for months. In the end, Doria resigned and moved back home rather than endure it any further. Still Elvira kept it up, to the point where half the country had heard about it. In despair, Doria committed suicide, like one of the characters in his operas. Puccini protested his innocence, but the country split into two opposing, accusatory camps. Only when the doctor’s autopsy revealed Doria to be a virgin did the fog begin to lift. Was there more to it? It seems unlikely that we will ever find out. But Puccini contemplated legal separation from his wife, while Doria’s family filed suit against her. Elvira was sentenced to five months in prison, before the case was settled out of court. Puccini could never quite forgive his wife after that, though they were reconciled later in the year.

Turandot was composed many years later against the backdrop of these meditations. It was first performed in April of 1926 at la Scala, minus the concluding duet, for Puccini had died before completing it, in 1924. The opera’s story was based on what some believe was a Persian fable but Puccini located it in ancient Peking to give it a timeless and universal quality. For the politically minded, it could have been set anyplace else that has experienced, or is experiencing a Reign of Terror, like the Middle East. For the Princess Turandot has vowed to exact revenge against all men for an original sin committed against her ancestress. She has therefore set three riddles for her suitors, and any suitor who cannot answer the riddles is beheaded. The kingdom is dripping in blood and Turandot herself has become a virgin ice queen – a beautiful but cruel avenger. As the opera begins, the last suitor, the Prince of Persia, is being executed. A new prince, young Calaf, arrives in Peking, but he is in disguise. Instantly smitten with Turandot’s beauty, he wants to try his hand at answering the riddles. His father and the young slave girl, Liu, try to talk him out of it. Liu is in love with him but Calaf doesn’t know it.

Calaf successfully answers the three riddles (the answers, it turns out, are Hope, Blood and Turandot) but now Turandot fears being given over to this foreign prince with no name. So Calaf comes to her rescue by setting a riddle for Turandot in return: if anyone can find out his name, he will agree to his own execution as if he had failed the riddles. That night no one sleeps as the search is carried out (no one would want to during the marvelous aria “Nessun Dorma”). When Calaf’s father is captured and threatened with torture, Liu steps in to save him and is tortured in his stead, but courageously she refuses to reveal Calaf’s name. Turandot is curious about where she gets her strength to resist and Liu responds, “Princess, it is love.” When the pain becomes unbearable, Liu criticizes Turandot to her face before grabbing a soldier’s dagger and taking her own life. Everyone is appalled: so much blood has been spilt already but this time it’s different, for this woman has died for love. Calaf criticizes Turandot at first but then kisses her on the mouth and it would seem that she becomes his. At the court, she declares, “I have discovered the stranger’s secret and his name is – Love.” The Reign of Terror is over. But this last part isn’t in the opera, because it stops with Liu’s death… unfinished. Like all the world's most intractable conflicts.

So why do men fall in love with ice queens and not the women in front of their eyes? Who is the hero of this story – Calaf, Liu or Turandot? The libretto suggests that it is the power of Calaf’s love to melt Turandot’s cold heart, so that ice becomes fire, and life triumphs over death. But this explanation flies in the face of the emotional impact of the opera, for it is clear that Liu is the true heroine of the opera, not Turandot, just as Madame Butterfly is the heroine in her opera. Puccini’s operas defend the brave young women who are destroyed in the course of the story by forces greater than they, but none more poignantly than Liu. She is completely Puccini’s creation and she gets some of the best music too. But it has greater resonance in that Puccini was mindful of the suicide of Doria Manfredi and innocent victims everywhere. There is a sense of atonement, sympathy, pathos, even rage that drives Turandot that is not there in the other operas. Turandot herself chooses to be the victim of the original sin, but equally she is the cause of the current series of riddles and the blood it spills and one might see the shadow of Elvira, Puccini’s wife, behind this chilly figure.

A number of music critics make the connection between Doria and Liu (to be fair, many do not). I have yet to read anyone make the connection to Mata Hari, and Puccini only saw her perform that one time in Monte Carlo. But in the early 1920’s, as Puccini wrote Turandot, Europe was still coming to terms with the barbarism of what had occurred during World War I and the traumas that would not heal, least of all in Italy, where Mussolini was on the rise. The Great War had absolutely horrified Puccini. He was criticized because he had showed his distaste for it (by being facetious) while everyone else was plunging headlong into it. When the War was over, while he always had a fondness for the monarchy, the church, the old ways, this did not mean he automatically embraced fascism or nationalism, or rejected them for that matter.

That kind of rigid thinking he rejected was exactly what had brought about the suicide of Doria Manfredi, the one person who had behaved honorably throughout the whole fiasco. It was that kind of malice that had brought about the death of Mata Hari nine days before the Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace. Like Mata Hari, Puccini believed in individualism, not mass ideologies. He believed in the right to go hunting and to drive fast cars, he believed in the right to flirt and the intoxications of love and lust. Mata Hari was a symbol of love, and in Paris in 1917 that was the ultimate transgression in a political culture of death. Cynics may argue that Puccini was just a womanizer and that he allowed himself to be used by Mussolini, but people behave in love the same way they behave in politics and he made them both the backdrop to Turandot. He understood the relationship between them.

Puccini was pessimistic that humanity could ever achieve harmony again. It is somehow fitting that harmony is almost achieved in Turandot, but it isn’t, because the opera is unfinished, and some critics argue that the happy ending was beyond his ability to deliver. The onset of the modern world would be dominated by the great ideologies: bolshevism, communism, fascism, nationalism and the like. This was a discordant time. In the theater, the concert hall, the opera house and the music hall, things were in rapid decline. Turandot would be the last great opera and no one would live happily ever after.