Napoleon as Ozymandias

In 1815, when Napoleon escaped from the island of Elba, Byron wrote in a letter how much he admired Napoleon, the Romantic hero he wanted to be.

It is impossible not to be dazzled and overwhelmed by his character and career. Nothing ever so disappointed me as his abdication, and nothing could have reconciled me to him but some such revival as his recent exploit; though no one could anticipate such a complete and brilliant renovation.

Shelley felt differently. In 1816 he wrote in Feelings of a Republican on the Fall of Bonaparte:

I hated thee, fallen tyrant! I did groan

To think that a most unambitious slave,

Like thou, shouldst dance and revel on the grave

Of Liberty.

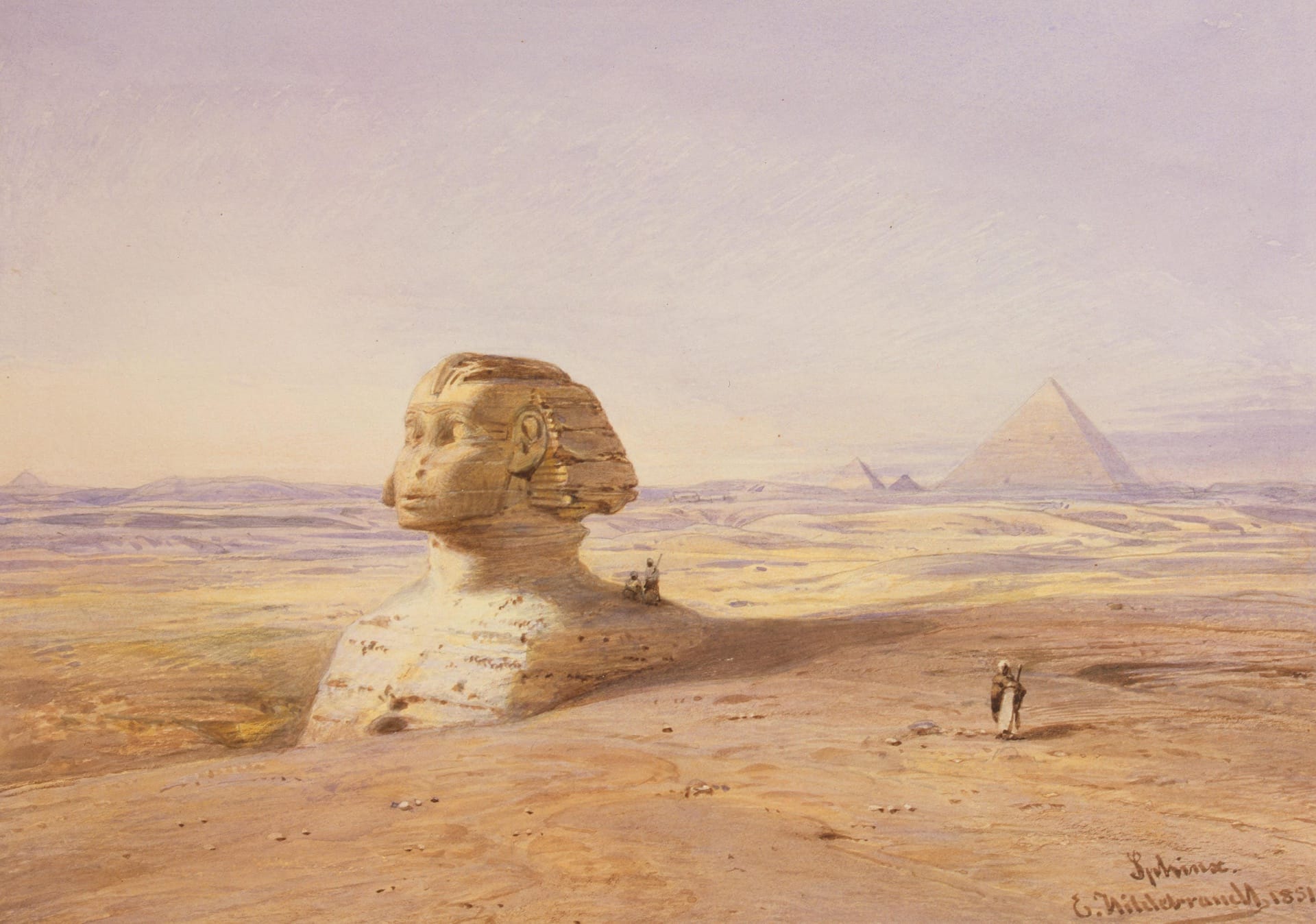

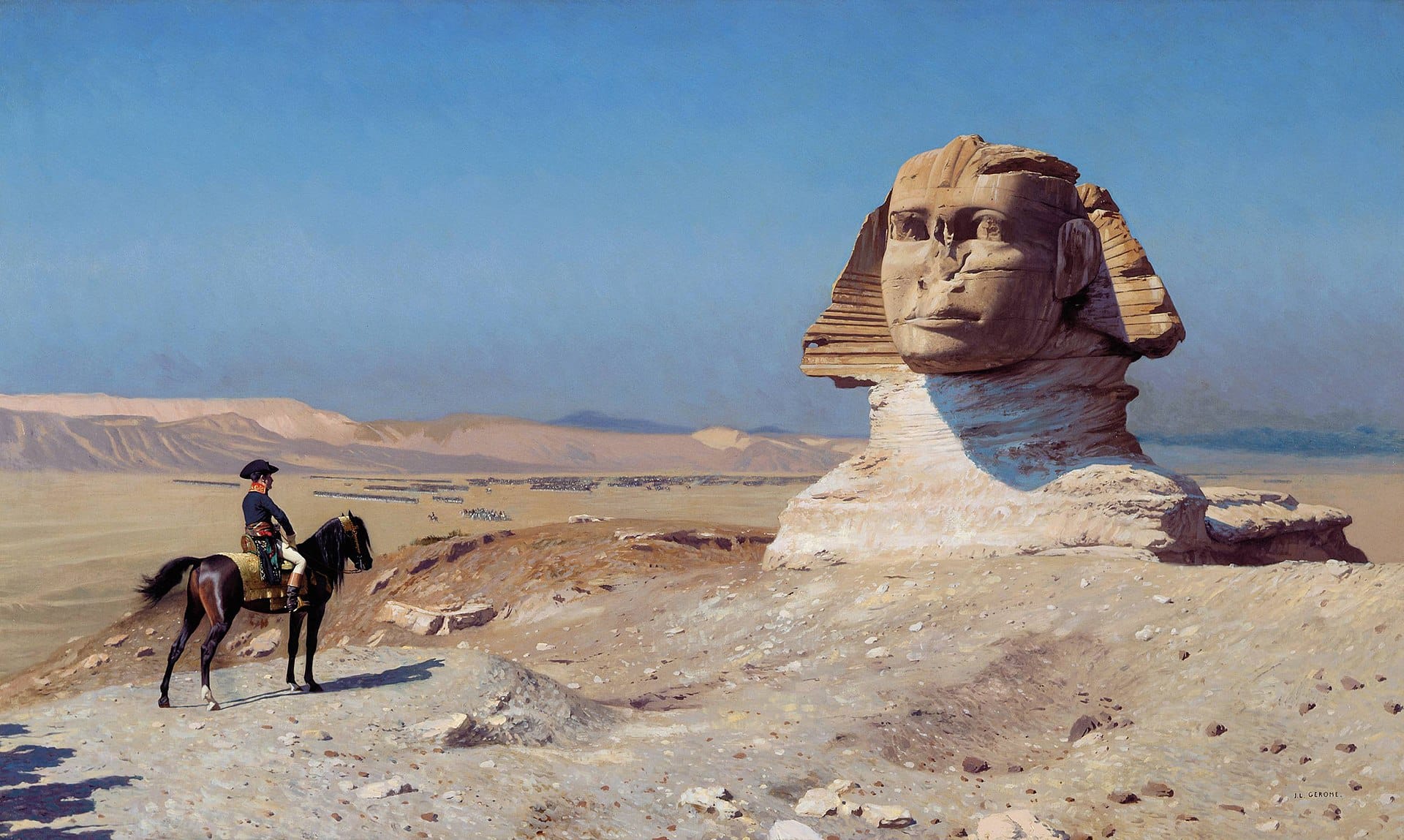

For Shelley, Napoleon was a bloody tyrant who had betrayed the Revolution, a vain Ozymandias (1818). That image resonated because it was during Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798 that the Rosetta Stone was rediscovered and Europe made its formal reacquaintance with the Sphinx herself.

For Shelley, there was a sense of illegitimacy here that was spiritual - we are all in a "waking dream." Life itself was illegitimate, a "ghastly dance" (these are quotes from his final poem, The Triumph of Life in 1822). He had a point, of course, for the vast gap between rich and poor in England was at its widest during these decades. If Byron's reaction was individualistic (I too am an orphan), then Shelley's was generalized (we are all orphans). Byron imagined himself as Childe Harold, Don Juan, Manfred, Cain and Lucifer, but Shelley seems to have thought we are all the vain Ozymandias or the tortured Prometheus.

The Sphinx herself - the original mythological figure - has provided for an equally rich symbolism as Napoleon. For Francis Bacon, writing in Wisdom of the Ancients (1609), the Sphinx could be science itself: "For science may, without absurdity, be called a monster."