Splendour in the Grass

The Bastards of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The Bastards of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Once upon a time, in a faraway Gothic house with a gabled roof, a young woman gave birth to a baby girl. According to the birth certificate, the only witness present at the birth was Sophia, a midwife and mother of Jessie Whetton, and Jessie was not married. One of the unexpected things about sex is it has side effects, like children.

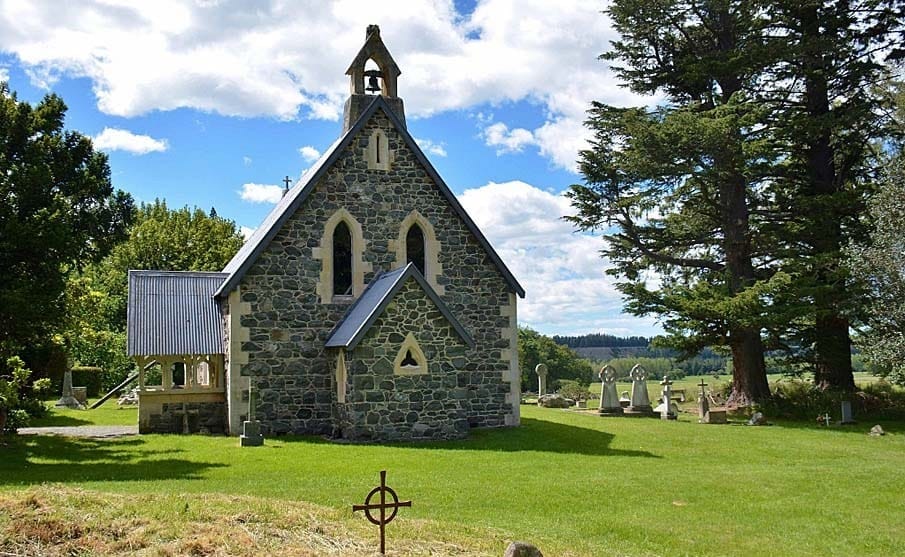

Mount Peel Station

The baby, an "unnamed Whetton child," was born on September 14, 1896, at Mount Peel sheep station in the foothills above the Canterbury Plains of New Zealand, where the roaring Rangitata River breaks out of the Southern Alps and rolls to the sea. In the years when the snow was heavy, thousands of sheep would die - the previous year had brought the worst snow ever. It is a wild place still, a white water rafting area and travelers have drowned there. Upriver, in the brown grasses and rocky outcrops, is where Edoras and other scenes in The Lord of the Rings were shot. So is Mesopotamia sheep station, where Samuel Butler stayed for four years, before fleeing back to London to write Erewhon.

At Mount Peel near the homestead there is a small stone building, the Church of the Holy Innocents, so-named for four infant children who died here between 1864 and 1869. They are buried in the churchyard cemetery. So too is crime writer Ngaio Marsh - imaginative people plan out where they want to spend the afterlife. Immigrants from around the world arrived here once, as refugees, and the gravestone epitaphs speak not just to the fragility of life in a strange new land, but to even stranger tales from the forgotten past. They are poems sent into the future like messages in a bottle, written by surviving spouses, parents, children. They are couched in religious language but that is just convention. It is the emotional content behind the words that matters - the grief is palpable.

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting.

Jessie Whetton was in her teens when she emigrated with her family to New Zealand from the south of England. It was the late 1880’s. Her parents gained employment at Peel Forest and, we think, that is where she met the father. Robert Shanks lived in Timaru or Temuka and he may have been much older. Perhaps he was married? Perhaps he traveled around a lot as an itinerant worker, perhaps as a shepherd. Jessie became pregnant to him in early 1896 and their daughter was born in September at Mt. Peel. At three weeks the baby was taken to Dunedin and given to a foster family, the Sarneys. It would be a happy and loving home, but Jessie Roberta Shanks (she retained her mother's first name and her father’s last name), would never see her mother again. That was the way they did things back then.

Every birth is special, a miracle… It is a sentimentalism, of course, but it is preferable to call someone a miracle than to call them an “illegitimate child” as though that term means anything legitimate. It has fallen out of favor, but it was used in a time when responsibility for unexpected children increasingly fell upon the father if he was an honorable man.

What must have been decided in those winter months of 1896 as Jessie Whetton’s pregnancy became obvious? Indeed, did it become obvious? Who made the decision that the child’s mother would disappear from the child’s life? Did she have any say in it? Would keeping the child have marked her as a fallen woman? We have assumed the relationship was consensual but we don’t really know.

After the birth, the Whetton family moved away north to Aramoho, Whanganui, where the young woman married one Albert Major in October of 1897. The Major family was from Geraldine, very close to Peel Forest, and they had moved to Whanganui a few years earlier. So, we assume that Albert already knew Jessie from Peel Forest, for when they were married, she had been in Whanganui barely three days. It also seems likely that the new husband, Albert, would have known of the earlier child, since the records of Peel Forest show that several members of the Major family worked there too. These families were laborers and cooks and they would have talked. Albert and Jessie Major eventually became a farming family south of Whanganui and they had four children. Albert died in 1940, aged 69, but Jessie lived to be quite old, dying in 1966, aged around 90. She was a staunch Anglican, quite an austere person and a very keen gardener.

In Dunedin, meanwhile, the child – my grandmother - was supported financially by her father Robert for nine years and then the money stopped. On the last time he visited her, she was 14, and she remembered that visit because he kissed her (as her Uncle Robert). It must have had a profound effect, because she told her own children about it, which implies that she suspected he was her father. For adopted or orphaned children, there is no more potent force in this life than the existence of a blood relative.

There were other Shanks families in Dunedin, but most studiously ignored her (but not all). She never told her own children of the exact circumstances of her birth and she must have wondered what happened to her father and her mother. Perhaps her father was leaving the country? His marriage had petered out? The family heard from him no more. And what of her mother? In her later years Jessie would say that her parents had been married and that they died in a carriage accident when she was a couple of weeks old and she had photos to prove it. Did she invent the story for herself or did the Sarneys invent it for her?

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.

Melodrama may be a maligned genre but it frequently poses interesting moral questions: do your thoughts turn toward the most vulnerable person in this story? But who is that? The foster child, the orphan? What about Jessie Shank's father? Can you imagine him struggling to raise a young family and paying for his secret daughter? Or do you see him as a rapist, a fool? What of Jessie's mother and her family? Do they recede from sight - is there a heart of stone there, or a poor family overwhelmed by circumstance? How can we ever measure secret grief?

Wordsworth's 'Splendour in the Grass'

The poet William Wordsworth had his own “illegitimate” daughter. This only became widely known in 1921, a discovery that shocked his admirers, who rather liked his prudish Tory reputation.

He wasn’t always that way, of course. The events of 1802 reveal a very different man. In August of that year, during a momentary peace between England and France, he crossed over to Calais to meet a daughter he had never seen, 9-year-old Caroline, and her mother Annette Vallon. They spent a month together, during which it seems they became reconciled to never being united as a “legitimate” family. Most Wordsworth biographers assume this was a matter of some relief to him, for he returned to England and married Mary Hutchinson in October and it was a happy marriage by all reports. Vallon never married.

A decade earlier, in late 1791, when the 21-year-old Wordsworth had met the 25-year-old Vallon in the city of Orléans, the French Revolution was in full swing. He was Protestant and excited by the writings of Rousseau and the Republican revolutionary fervor in the air; she was Roman Catholic and strongly Royalist. In one of those moments when desire drives all else out the window, the relationship flourished and Vallon became pregnant. It may be that her family tried to keep her away from him, something hinted at in his poem Vaudracour and Julia (it’s not one of his best), or it may be that her family were quietly supportive and even thought the couple had married secretly. We don’t really know. But, events deteriorated around them and in August of 1792 the Revolution transformed into the Reign of Terror. The storming of the Tuileries and the arrest of Louis XVI were followed by the massacres of September, and what Wordsworth saw in Paris in October and November seems to have appalled him. If he had any thoughts of returning to marry Vallon, he didn't do so. We know she gave birth to their child, Caroline, on December 15, a few weeks after he had returned to England.

Could the marriage have worked out even at the best of times? It seems unlikely and he may have known that. It helps explain his repeated deferment of marriage and his behaving honorably toward Vallon in later years. He could not have predicted that England and France would go to war again and that it would last a decade. Vallon wrote intimate and moving letters to Wordsworth, but they were intercepted by French authorities so he never saw most of them. Only one survives and it is intense and passionate; she addresses him as “my lover, my husband.” Of course, Wordsworth's biographers have uncovered a record of Vallon's extensive counter-revolutionary activity during these years, prompting the question: did she exploit Wordsworth's connections with the revolutionaries and did he know it?

Wordsworth’s greatest poem, Ode: Intimations on Immortality, was written during these turbulent years. It is his best as much for its autobiographical qualities as for its great lines. The first 4 stanzas were composed in March of 1802, when he was contemplating marriage to Mary and transition into respectable adulthood and parenthood. However he was dealing with Coleridge’s imperious demands that they all go and live together in Bordeaux, and then there was the arrival of Vallon’s emotional letters from France. He turned 32 in April...

After the Calais reunion in August, Wordsworth wrote the poem It Is a Beauteous Evening, Calm and Free, where he addresses his daughter: “Dear Child! dear Girl! that walkest with me here,/If thou appear untouched by solemn thought,/Thy nature is not therefore less divine.” This is proud and defiant language, if a little pompous. But it is in the Ode that he develops the profound and deceptively complex concept of "The Child is father of the Man" that speaks to that lost relationship:

What though the radiance which was once so bright

Be now for ever taken from my sight,

Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower;

We will grieve not, rather find

Strength in what remains behind;

In the primal sympathy

Which having been must ever be;

In the soothing thoughts that spring

Out of human suffering;

In the faith that looks through death,

In years that bring the philosophic mind.

Evoking Milton's Paradise Lost and Rousseau's Émile, the Ode expresses a powerful spiritualism and nostalgia. It would seem that this was motivated at least in part by his reflections on a lost lover and a lost daughter, a “Child of Joy” that he had once lost and then regained. There is a maturity to Wordsworth's writing and his career arc that is simply missing in the later Romantics like Byron and Shelley, who threw away women as if they were mere distractions.

The war resumed the following year, 1803, and did not end until the first abdication of Napoleon in 1814. During those years, Wordsworth was unable to see Vallon and Caroline, who now were living in Paris. Caroline married in 1816, using the name Caroline Wordsworth, in honor of her father. He provided for her dowry, but he seems to have decided it would not be appropriate for him to attend the wedding. Yet he never kept any of this a secret – at some risk to himself - and it is somewhat surprising that the matter never emerged more publicly throughout the 19th and early 20th century. It did not help that his widow Mary would instruct his nephew and first biographer to destroy all evidence of the French "relatives." Which he duly did.

Rousseau's Bastards, Foundlings and Orphans

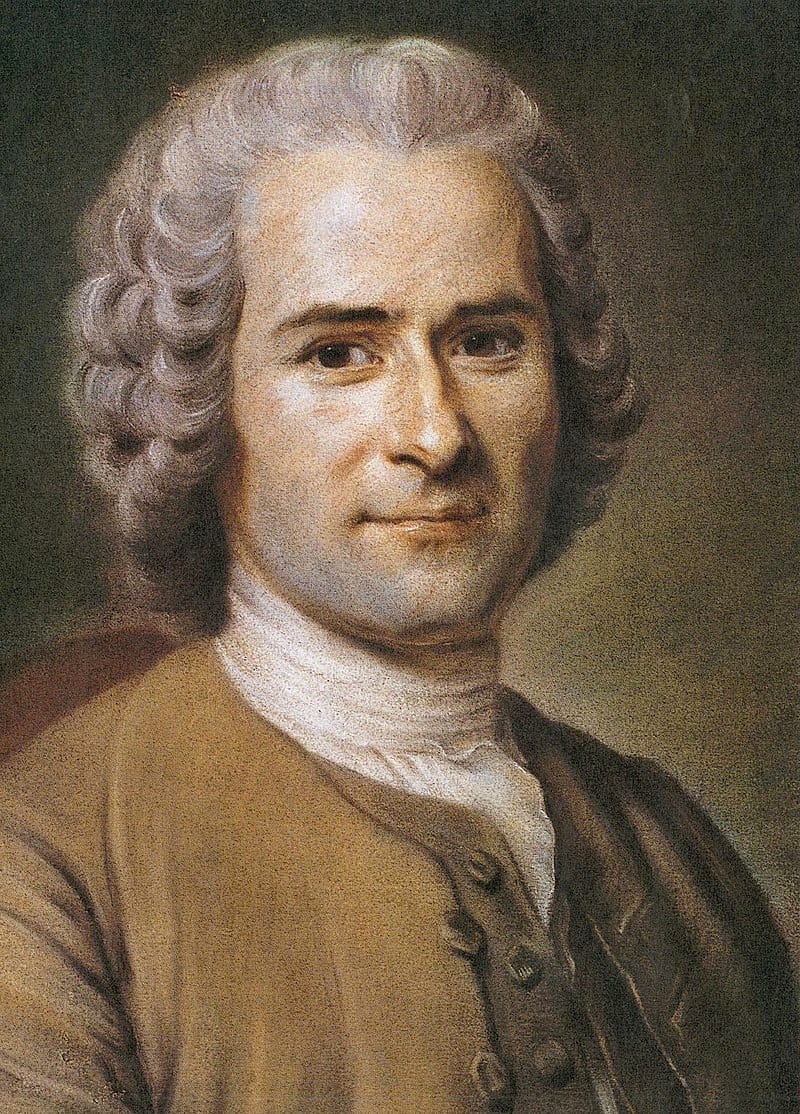

It was customary in the late 18th century, as it is today, to blame the ills of the world on the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, not because his ideas helped inspire the French Revolution (as well as the American one), or literary and musical Romanticism (including Wordsworth), or reforms in education and parenting, but because his ideas in Discourse on Inequality and Émile and Of the Social Contract gave people hopes and aspirations they had no right to have.

For this he was slandered and libelled and stones were thrown at his house. Some of those stones were thrown by highly civilized contemporaries like Voltaire and David Hume and Samuel Johnson; even Diderot threw a few. The assault continued after his death, with Edmund Burke and Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley and Lamartine and George Sand and Hannah Arendt. Today's right wing pundits blame him for Communism, Fascism and the kitchen sink and left wing pundits don't like him either.

Indeed, Rousseau has to be the most misunderstood philosopher of all time. How else to make sense of the fact that two people can read the same passages - forget the politics, try his writings on masturbation or lusting after a beautiful woman - and come to opposite conclusions? Yet, all along, Rousseau was rather consistent, embracing his past as the son of a Genevan watchmaker, and embracing his present as an intellectual foundling and truth-teller, with a finely developed sense of the absurd. As biographer Leo Damrosch puts it: "It was Rousseau who was the most original genius of his age - so original that most people at the time could not begin to appreciate how powerful his thinking was."

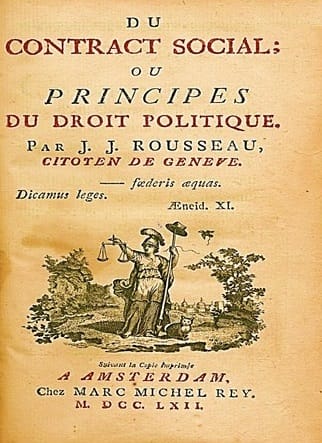

When Rousseau became famous all across Europe from 1751 onwards, he was nearly 40. His criticism of the arts and sciences and philosophy as selfish and elitist was precisely understood at the time. His critics resented his charge that civilized society - their society - was corrupted, as well as his implication that they all wrote in bad faith. They further resented his refusal to publish his work anonymously (highly unusual at the time); Rousseau considered it a matter of personal responsibility to use his own name. Worse, by the time he began writing what I think of as his sexual fables, they were far more "popular" than theirs; Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (1761) was the most popular novel of the 18th century. Émile, or On Education and The Social Contract (both 1762) were considered so dangerous they were banned and burned.

The misunderstandings only increase when his writings are juxtaposed with how he chose to live his life. Rousseau, following Montaigne, insisted that understanding his life was essential to understanding his writings. But, in attempting to live his ideas, he provoked his critics to retaliate. They called him irresponsible and unstable, a libel that exists uncritically in many biographies and articles today, even some academic ones. When they are not blaming him for his writing, his critics are blaming him for his vanity and his shoddy character. They cannot fathom his willingness to live with constant financial insecurity, or the time he spent with local villagers talking about such mundane matters as breastfeeding or swaddling clothes, or his frankness about his sex life, or his decades-long relationship with the "pretty seamstress" Thérèse Levasseur, whom he never married officially, but who was more or less his wife.

The most common libel was (and is) that the five illegitimate children that Rousseau had with Thérèse between 1746 and 1752 were given away to a foundling home, L'hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés, where it is likely they all died young. Some have argued that this was against the wishes of Thérèse, and that Rousseau incriminated himself when he wrote that some people simply shouldn't have children. Voltaire, who never had children himself, in one of his fits of pique "exposed" this scandal in 1764 with an anonymous attack on Rousseau, known as Sentiment of the Citizens. Mary Shelley was one of many who picked up this line of attack, angrily denouncing Rousseau for his "vein of insanity" in how he treated his children. She was a fine one to talk.

Nowadays some concede that perhaps there were no children and that Rousseau only claimed there were, or that he was tricked into believing there were, but this only leads his critics to a prompt indictment of Rousseau's naivete, his (lack of) virility and his overly sensitive and paranoid nature!

We only have Rousseau's word for it that he had any children at all, of course, in Confessions (completed 1769 but not published till 1782, after his death). Confessions is not an autobiography really; it is a series of sexual fables and it surprises me that so many believe him to be obligated to report the "facts" of his life when he does not appear to share this belief. When his critics point out the errors and contradictions ("lies") in Confessions they again miss the point that Rousseau played around with the "facts" because they were unimportant except in how they could address larger moral truths about life and frequently indirectly at that. All his writing is subtly ironic and not to be read literally.

Rousseau's relationship with Thérèse lasted for many decades. Like all "marriages" it had its crises but it was built upon affection and trust and it easily survived the sneers of Rousseau's contemporaries. If indeed he did have children with her, it seems unlikely he ever saw them. The custom back then was that midwives took them away to the foundling hospital immediately after the birth. Historians have noted that Rousseau's actions were fairly typical for the time - aristocrats and notables routinely dispatched their children to live elsewhere with wet nurses - and that if Thérèse acquiesced, then it was five times! From his writings though, especially Émile and Confessions, it appears that not only was he very familiar with child-rearing practices, even though he considered it women's work, but that he felt he had made a serious mistake in the matter of his children, and so we have Émile.

For the vast majority of the population - the masses of the urban and rural poor - "illegitimacy" was an irrelevant concept, since no one was married and bastards were everywhere. In Rousseau's Geneva, marriage was the privilege of a tiny minority of "citizens" who had property rights. Rousseau seems to have realized that illegitimacy is an accident of birth. To assert its existence while privileging marriage was a contradiction of the belief in moral equality. It implies that some lives are worth less than others, that some lives are not divine. Rousseau was not free of prejudices by any means, but if all people were born equal under God, then how could anyone support the divine right of kings, or the class system of master and slave, or slavery, or poverty, or discrimination against women and children and other religions? The Social Contract was his answer - all citizens would be equal before the law.

Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.

When Rousseau's bastards revolted, in events otherwise known as the American and French Revolutions, this only confirmed the suspicions of the Georgian and Bourbon aristocracies. What, after all, was the young America, once it had declared independence, but an ungrateful illegitimate child? What else was the Reign of Terror or Napoleon's behavior but more illegitimate "monsters"?

Illegitimacy only became an issue (pun intended) with the expanding middle classes amassing fortunes and the religious revivalism and charity work over the next century, the "bourgeois" century. As social unrest grew, real efforts were made in Europe to improve the lot of the urban poor and integrate fathers into their children's lives. As inequality and illegitimacy declined, illegitimate children remained stigmatized. This was the era of the notorious "baby farmers." (Is there a correlation today? Just as the inequality gap is widening again rapidly, and people in their Twenties are forgoing marriage, illegitimacy rates have gone back up over 40% in the U.S. and Europe after being under 20% in 1980).

Shelley and Byron - the Disinherited

1816 was the "year without a summer," when crops failed all around the world and everyone huddled in front of the fireplace. Toward the end of the year, a despondent Harriet Shelley, the beautiful and talented young wife of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, drowned herself, Ophelia-like, in the freezing Serpentine in London. She was just 21 and pregnant.

Harriet's suicide followed close on the heels of the suicide of another in their circle, Fanny Imlay, prompting the question: what happened to these young women? Many decades later, an outraged Mark Twain would write In Defense of Harriet Shelley, in which he ripped facile Victorian Shelley biographers, protesting, "Her husband had deserted her and her children, and was living with a concubine all that time!" Furthermore, Shelley married that concubine, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, less than two weeks after Harriet's suicide.

The most striking thing about the sexual lives of Shelley and Byron is the destructive effect they had on the lives of others, not least their inability to navigate married life and their poor treatment of women, as well as the premature deaths of their children. Shelley was only 24 when Harriet died and, while few men understand what is stake when they discard women and children in so cavalier a fashion, the Shelley of those years displays the passive-aggressive personality of the dilettante.

Shelley had eloped with the 16-year-old Harriet (Westbrook) when he was 19. Though they lived together briefly, sex seems to have been rare. Historians have enjoyed speculating on why he invited his friend Hogg to join them on the honeymoon. Perhaps it had to do with a belief in free love, perhaps it had to do with wanting to be a free spirit, not tied down to any one woman? At any rate the couple would have two children, but he abandoned her in 1814, running away to the Continent with Mary Godwin, who would go on to become the author of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1819).

Shelley's defenders argue that he had lost interest in Harriet - these things happen - and that he was a good father who loved his daughter Ianthe. His detractors, however, defend Harriet and criticize Shelley. Why did he let his friend Hogg hit on Harriet constantly - he surely saw what was happening? This is why Eliza, Harriet's sister, came to stay, which Shelley resented of course, but it was Eliza who ended up looking after the children.

Did Shelley intellectualize everything too much to appreciate his flesh and blood wife? Why else would he pursue Rousseau's lovers in Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse in a boat on Lake Geneva with Byron? His critics are equally unforgiving of Mary, who always seemed to be sick or grumpy. If she worried that their children were at risk, it didn't stop the couple from traveling and sure enough their children died young anyway, from fever and from being constantly on the move. Shelley himself was dead at the age of 29, in 1822, drowned off Viareggio in July. From then onwards, Mary fostered the vision of Shelley as a glorious doomed angel but the trouble with angels is that they have their head in the clouds.

As for Byron, another death had occurred earlier in 1822 - in April - Byron's 5-year-old daughter Allegra.

But first we have to go back to 1816. After Byron's marriage failed in January of that year, he left England, leaving behind him a trail of wreckage straight out of a Gothic novel. It involved Lady Caroline Lamb (mad obsession), his half-sister Augusta Leigh (rumors of incest), his wife Annabella and their daughter Ada (marital violence and child abandonment) and affairs with miscellaneous chorus girls. No more boys apparently (his earlier Greek adventures), but no wonder he never returned to England.

Byron would find his way to the Villa Diodati near Geneva in 1816, where he met Shelley, Mary Godwin and her step-sister Claire Clairmont, who was among the other women Byron had had an affair with in London. Claire, it turned out, was pregnant and in January of the following year she gave birth to an illegitimate daughter that they named Allegra.

Before Allegra died of a fever in 1822, she was dragged around Italy by Byron (Claire was kept out of the picture) and deposited with different families and a constant succession of nursemaids. The last year of her life she spent in a convent. Byron apparently thought that she might be safe there from fevers and, Protestant snob that he was, he approved of the old Catholic traditions. Claire and Shelley vehemently disagreed with this, but Shelley's own children with Mary died young, so who was he to talk? In 1821 the four-year-old Allegra wrote a letter to break anyone's heart: "My dear Papa, it being fair-time, I should like so much a visit from my Papa as I have many wishes to satisfy. Won't you come to please your Allegrina who loves you so?" Yet Byron never visited her in the 13 months between the letter and her death. Why not? Byron himself would die of fever in Greece in 1824 at the age of 36.

In Byron and Shelley we have something new here: they seem to have embraced being illegitimate themselves. Not in the sense of having unmarried or deceased parents (they didn't), or in having illegitimate children themselves, but rather in a psychological sense where they rejected their inheritance altogether - their parents, property, traditional politics, along with the obligations of marriage and fatherhood. It was noticed. Shelley was virtually disinherited by his family after he wrote (with Hogg) The Necessity of Atheism in 1811, and then the radical poem Queen Mab (1813), which he dedicated to Harriet and published privately. Byron flirted with being disinherited and his poetry and plays are about virtually nothing else - Manfred (written 1816-17) for example. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is a guilt-ridden and literal approach to the same theme. The monster is the illegitimate child and the other characters are a reflection of Mary Shelley's own tortured family relationships.

I...was the true murderer.

Shelley and Byron both abdicated their responsibility for their children and their lovers in favor of a bid for freedom from what they saw as the ruins of a corrupted and decaying society. If the old world was represented by the crumbling architecture of the Gothic Novel, then they chose to be foundlings like Émile rather than sober philosophers like Rousseau. They wanted a new world altogether - preferably outside England and so they became Romantic wanderers, nourished only by the thrill of new lovers, vegetarianism, revolutionary politics, inspirational poetry, or a new boat. It wouldn't have lasted - they both would have returned to England soon enough - but it killed them before they could. They had misread their Rousseau, yet Rousseau read them just about right.

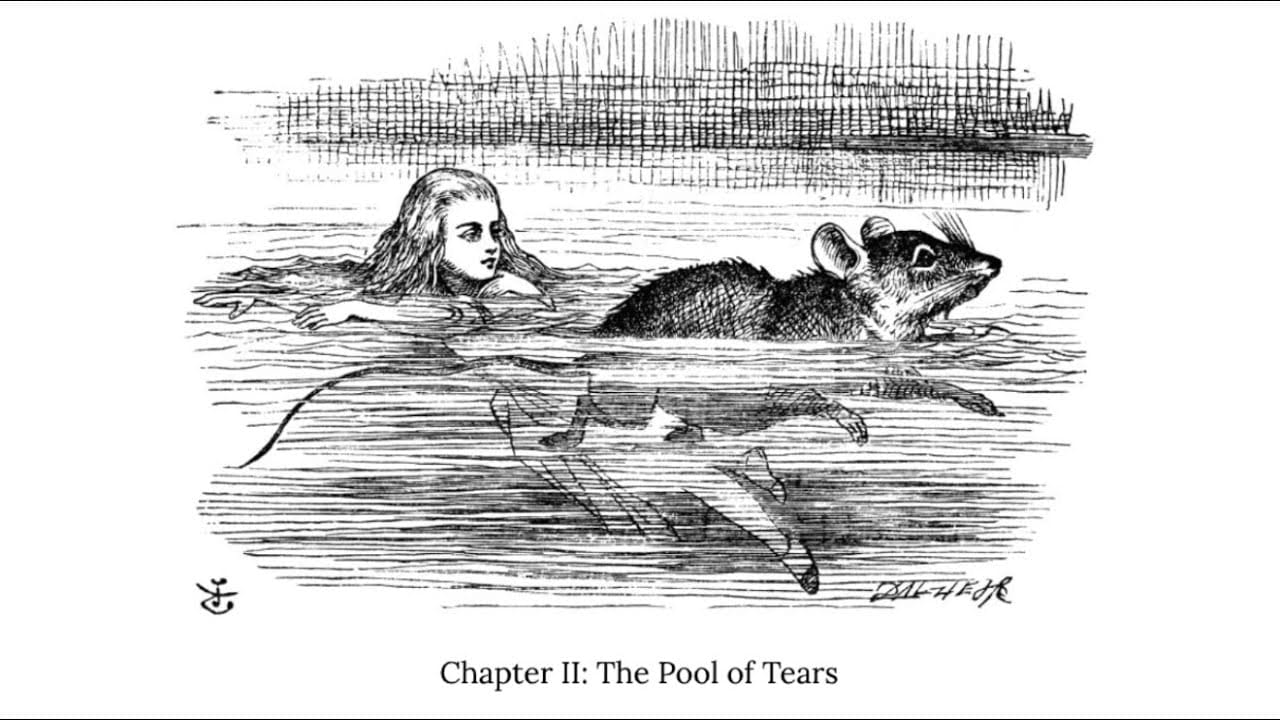

Lewis Carroll and the Pool of Tears

One of the stranger ideas in Samuel Butler's Erewhon or, Over the Range is that children choose to be born: "I came at last to the unborn themselves, and found that they were held to be souls pure and simple, having no actual bodies... The only form of death in the unborn world being the leaving it for our own. They are believed to be extremely numerous, far more so than mankind."

Perhaps he was simply taking conventional beliefs and making them literal in a Swiftian satire. Perhaps he was taking Darwin's abstractions about the origin of our species and giving them a spiritual dimension. Another way to look at it, is that for several decades European intelligentsia had begun to notice the sheer number of children in their midst and they were struggling to understand them as a different species, so to speak, expanding the debate beyond the bloodline metaphors that had determined legitimacy. They also had to come to terms with losing them too. Every family dealt with this, including Darwin, who was heartbroken at losing his daughter Annie at the age of 10, in 1851.

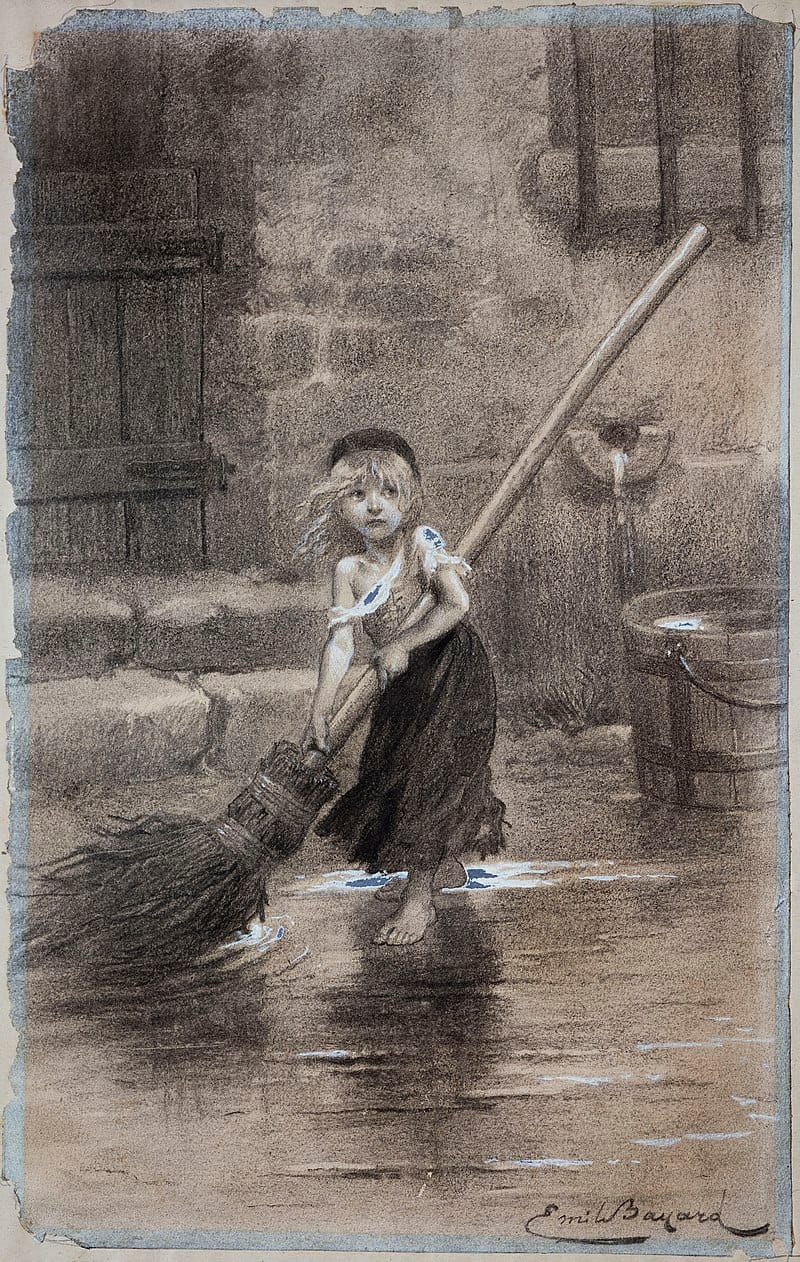

Butler opted not to marry; his novel was published in 1872. But, in the decades prior to this, many 19th century European novels and poems rushed to adopt orphans and those orphans now had histories that had to be accounted for, futures that pushed themselves forward and that would not be ignored. Perhaps their parents were dead; perhaps they would live to see their 5th birthday; perhaps they were heiresses. But now they needed to be explained! A deluge of orphans in literature followed, notably in the popular books of Charles Dickens, but also Heidi, Rapunzel, Jane Eyre, Peter Pan, Mowgli, Huckleberry Finn and others in painting, photography and greeting cards. It persisted well into the next century.

Children have nothing to lose but their chains.

This chapter has as much to do with children as the unexpected consequences of sex. Metaphorically it features water, rivers, lakes, the oceans between us, the plunge off the bridge, the deluge. Birth, of course, and orgasm perhaps, drowning and suicide, and the loneliness of illegitimacy, as well as the sense of a wave of children coming who have chosen to be born.

It was not all miserable, of course, but drowning symbols and metaphors recur in the poetry of Tennyson, the novels of Dickens and George Eliot, the paintings of the pre-Raphaelites - especially Millais and Waterhouse - and "children's" literature like John Ruskin's The King of the Golden River (1841), Charles Kingsley's The Water Babies (1863) and Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865). The drowning metaphor was rhetorical and polemical in the Victorian era: it was protest literature and much of it was directed against the exploitation of children.

This is a viewpoint lost on those who have assumed the worst, those who have tried to drown Lewis Carroll and his photographs in the pool of tears with their allegations of pedophilia. They see what they want to see in their looking glass, never the "Child of the pure unclouded brow/And dreaming eyes of Wonder!" Carroll was aware of the gossips during his own time and he refers to them in his clear-eyed letters as Mrs Grundy. What he is really doing here is showing defiance against the sexualizing of childhood (more here). It is a conservative religious position, consistent with wanting to preserve childhood and feminine innocence, not destroy it. He was an Anglican deacon after all. (This doesn't rule out masturbation, although the very thought of that just confirms his critics' disgust.) It also seems to be consistent with his strong opposition to the vivisection of animals and with his use of language (puns, personifications, games with logic) to create an analogous imaginative free space of the mind. You either understand this - most children do - or you fail utterly - most adults do. It is why Carroll found most adults predictable and rather dull. That's because they are.

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

Into Wonderland

In the end though, this chapter is about Splendour in the Grass. It is about fire, earth and air signs too, not just water signs. It is about the happier moments of throwing off all restraint - the joy of sex in the grass or elsewhere, and its equally happy results. The Victorians did throw off all restraint at times and children were the result.

Did Karl Marx have an illegitimate son with his housekeeper, Helene Demuth, in 1851? The evidence is not convincing. Dickens, on the other hand, had 10 children (he seems to have thought they were his wife’s fault), but did he squeeze in an illegitimate son with his housekeeper and sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth, in 1854, or with the young actress Ellen Ternan in the late 1850s and 1860s? These seem more convincing, although there is not a shred of solid evidence. George Eliot’s partner Lewes was born illegitimate and his wife Agnes had five illegitimate children during their "open" but doomed marriage. The list goes on...

These secret passions didn't always produce children: there was Wilkie Collins' complicated love affairs, or John Ruskin's obsessions with young Effie Gray and Rose La Touche, or William Hazlitt and the landlady's daughter. But with secrecy came guilt.

Today, illegitimacy is no longer much of an issue and the guilt is mostly gone. We could say that nearly half of all Western children today are born "illegitimate" because their parents are not married and, even when they are, the figures are complicated by divorce. It varies widely too: in Scandinavia, parents choose to remain unmarried; in the U.S. nearly seven out of every ten Black women are unmarried. Marriage and inheritance therefore are not the issue here anymore; parenting and family connectedness are. Bloodlines have been displaced by DNA and DNA doesn't care who your parents are...

But this chapter is not only about adults and parents; it is also about childhood reveries and innocence and how wonderful that is too. In all generations, being lost in daydreams or finding ecstasy in play or sex or music or drugs is about preserving that reality.

Emile, Rousseau’s treatise on education was published in 1762. In it, he reflected on his several decades of trying and failing to educate the sons of the rich. He speculated that if only he got the child early enough he might have been able to make a difference. I think in the end he didn’t really believe it: even after educating Emile well, the rest of Emile’s life went downhill. The problem was that the students were not that interested in being “educated.”

Children and teenagers today are the same way. They refuse the chains offered them by their parents and by the crumbling Gothic mansions of our political and economic systems and their propaganda machines, including the education system and the mass media. As the gap widens between rich and poor, and the tuned-out indifference grows, marriage is seen more and more as a declining institution and public schools resemble 19th century workhouses, but with cameras and chain link fences and calls for armed guards. Some young people survive as Frankenstein sleepwalkers, a condition that affects rich and poor alike, but others are engaging in a refusal that is not passive resistance. It is active resistance and technology gives them the means.

Today's kids live in a world of social media, where they are accused of short attention spans and succumbing to endless distractions, but really what they are about is creating the private and necessary spaces to daydream. They find escape in music or the internet or in texting and sexting. This is not a bad thing; it is just their reality. If Taylor Swift speaks more forcefully to today's kids than their teachers and parents, then it is not the children who are disconnected from reality; it is the adults and their ideas that have become illegitimate.