The Black Legend

The Black Legend (La leyenda negra) was a term invented by Spanish historian Julián Juderías y Loyot in 1914. He was referring to the way Spain’s era of imperial conquest in the Americas had been blackened over the centuries by Spain’s enemies.

Those enemies, he argued, were Protestant countries who engaged in their own empire-building – the Dutch, the English, the Germans and the French too - enemies who resented Spain’s successes. He had a point of course, but he argued this when Spain’s empire was already over.

Was colonialism and occupation worse under the Spanish?

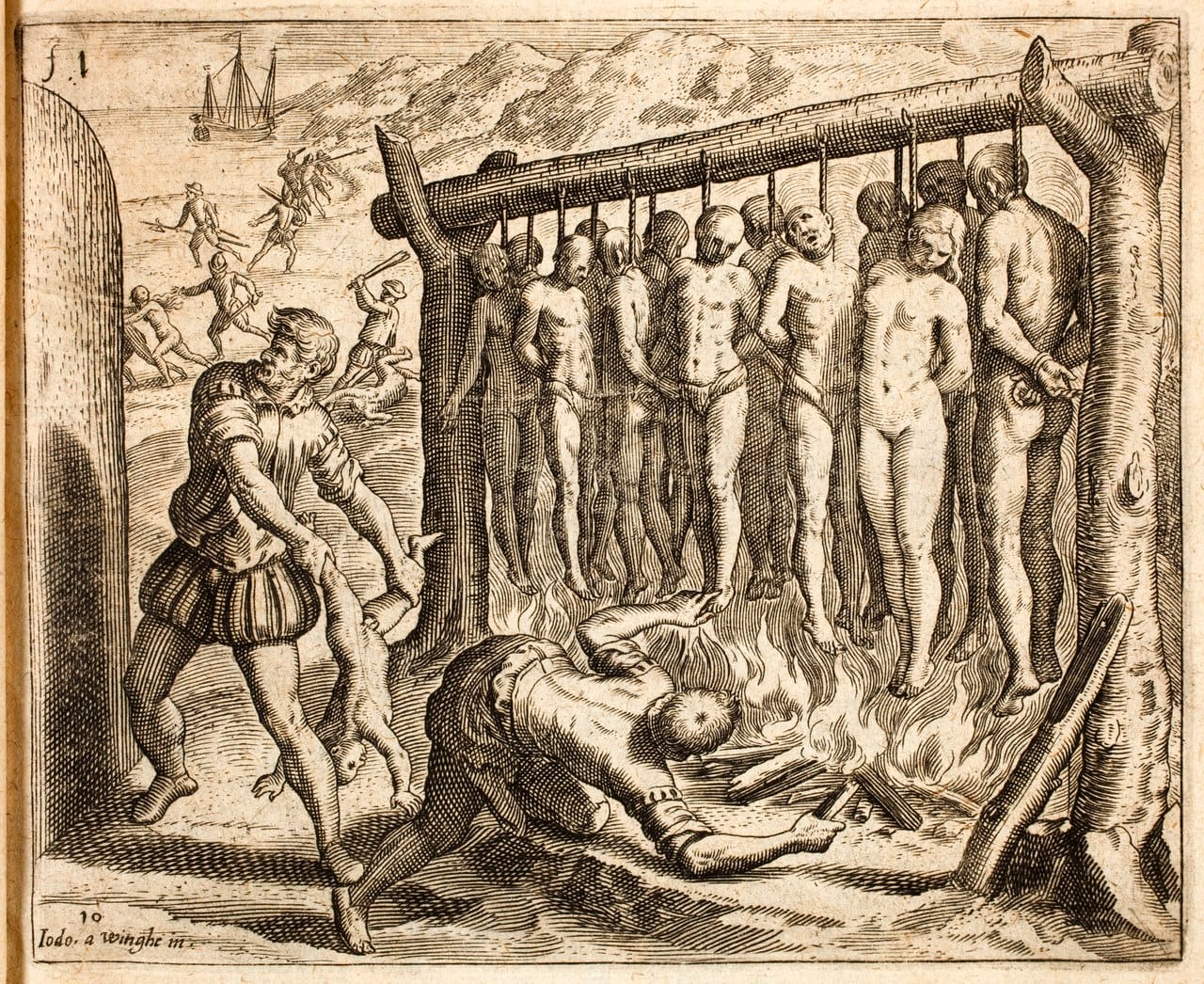

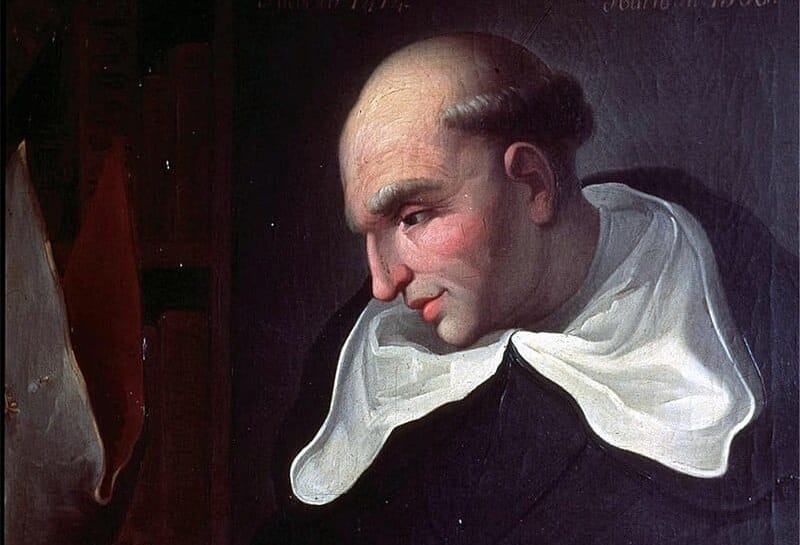

The formative period for The Black Legend was in the 1590’s and early 1600’s, following the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands and the threatened invasion of England in 1588. This was a time when the woodcuts of Theodor de Bry (like the one above) appeared and they swayed public opinion. The woodcuts illustrated books by the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas (whose portrait is shown below) and the Italian traveler Girolamo Benzoni, among others, and they were bestsellers. But were they also propaganda?

De Bry, who was born in Liège in 1561 into a Lutheran family, printed engraved illustrations that purported to show life in the Americas (he was based in Frankfurt). But the extremely graphic images of death and dismemberment created an image of Spanish imperialism that would persist for centuries. The term "The White Legend" was invented subsequently, during the Franco era, to present Spain's imperial era, and the Inquisition, in a more positive light.

It has been argued that in fact the Spanish were half-hearted imperialists, compared with the other European powers, and that unlike those others they were subjected to harsh internal criticism early on by Las Casas (A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies/Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, 1552). Similarly, it has been argued that with the Spanish Inquisition, procrastination and rationalization were the norm, unlike those other European powers where witch trials and executions were carried out more thoroughly.

But evil is a relative term. It really is impossible to defend the encomienda and repartimiento and hacienda forced labor systems employed throughout the Spanish colonies. Saying that the Spanish crown attempted to mitigate the worst abuses by passing laws, or that these systems resembled indigenous systems like the mit’a in Peru, hardly justifies the slavery and barbarism that resulted.

Similarly with the Inquisition. Seville, for example, where de las Casas was from, witnessed thousands of its citizens killed in autos-da-fé in the Plaza de San Francisco (many of its victims were Jews). In the Americas the Inquisition was active too. One of the most celebrated cases involved the Carabajal family who were executed in Mexico City in the 1590's for "Judaizing."

This legend goes back further though, to the Reconquista, when the Christian Spanish drove the Muslims (Moors), Jews and other "heretics" out of "Spain," then called al-Andalus, notably in 1492. This was translated into heroic propaganda, of course, such as Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo's novel Las sergas de Esplandián (The Adventures of Esplandián), from around 1510. Cervantes makes fun of it in Don Quixote. It is the story of Queen Calafia who ruled over a kingdom of Black women on an island off the east coast of Asia, and it is likely that Hernán Cortés named California after her, but I would think Montalvo had the Moors in mind. In the story, Calafia is captured by the Spanish, Christianized and married off. Spanish readers approved and the book was a bestseller.