The Rise of Vegetarianism as a Class Issue

Shelley and Byron defended and practiced vegetarianism. At the time they were called "Pythagoreans" (the word “vegetarian” appeared in the 1840's). They integrated their vegetarianism into a broader philosophy inherited from the Enlightenment, where eating meat was associated with aristocratic gluttony and consumerism, as well as Europe's encounter with India, which spread awareness of a successful vegetarian culture.

These Romantic poets, however, were reacting against the fact that the aristocracy could afford meat and the working classes could not. The poor got by on enforced vegetarianism - potatoes and vegetables. Shelley wrote A Vindication of Natural Diet (1813) during his first marriage to Harriet, and his second wife, Mary, made Frankenstein’s monster a vegetarian. Byron seems to have believed that meat had a negative physical effect on him.

They were not the first to say these things. Yet, over the centuries, very few have turned vegetarian for ethical or class reasons. Leonardo, Tolstoy and George Bernard Shaw perhaps.

Then there are Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, Rene Descartes, John Locke (who promoted a vegetarian diet for children, in 1692), Alexander Pope (who wrote the essay, Against Barbarity to Animals in 1713), Samuel Richardson (who became vegetarian late in life for health reasons), Rousseau himself (Émile contains a defense of vegetarianism) - they were all in favor of meat-eating as long as the killing was humane.

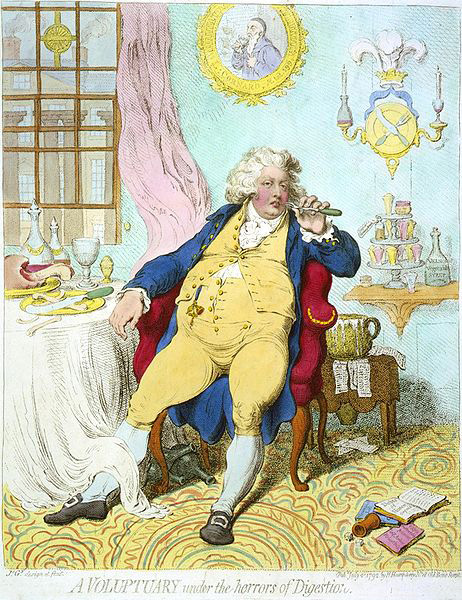

The caricature above is A Voluptuary under the horrors of Digestion by James Gillray around 1792. It shows George, Prince of Wales, later George IV, who was a known glutton. Such frank satire of the royal family surprised foreign visitors, but freedom of speech was well recognized. Unfortunately the ruling classes remained largely indifferent to the plight of the poor. Enforced vegetarianism can have harsh consequences.

Ireland and Scotland were devastated by the potato famine that lasted from 1845 until 1852, when approximately 1 million people died in Ireland and a further 1 million emigrated in the "coffin ships" (above). Aside from the horrors of the class system, oppressive landlords, cruel evictions and English indifference, the disaster was also the result of a monoculture - not just dependence upon the potato but upon one specific type, the Irish Lumper, whose reduced genetic diversity made the entire country vulnerable to blight, Phytophthora infestans.

The photo above shows The Great Famine National Monument at Murrisk, in County Mayo on the west coast of Ireland. The monument was unveiled in 1997 to memorialize the coffin ships that took Irish emigrants to the United States and Canada - many died on the way. The bronze sculpture is by John Behan; the photo is by Bruce Hall.