The Judgment of Paris

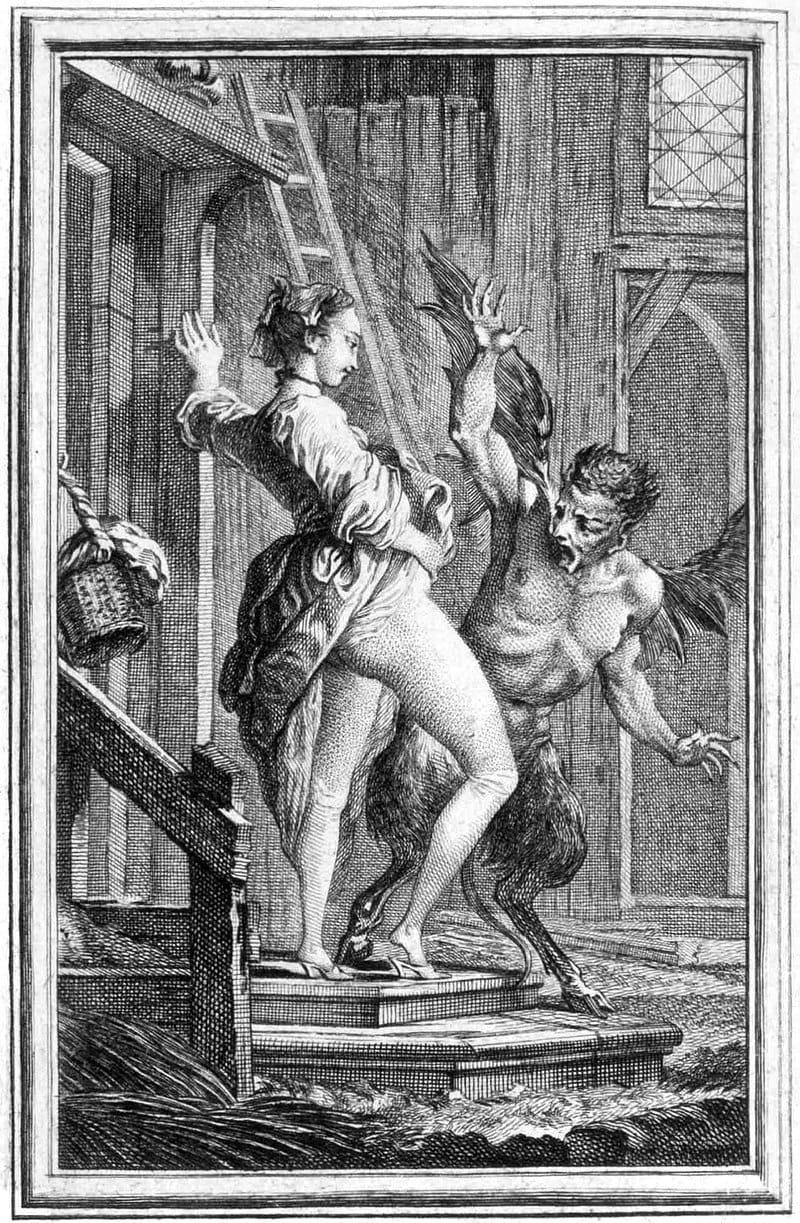

How Ninon de Lenclos Cheated the Devil

THE NOCTAMBULE

Once upon a time, a young French woman named Ninon de Lenclos was at home on Sunday morning when there was a knock at the door. On the step was a little white-haired man dressed in black. He introduced himself as the Noctambule (“Sleepwalker”) and he said he was there to offer her a choice of three things: the highest rank in the land, great riches and fame, or eternal beauty. But she could choose only one…

Cynics will want to note that intelligence was not one of the choices but let us assume that Ninon had that to start with. Like Paris in The Judgment of Paris, and this historic scene is occurring in Paris, Ninon chose eternal beauty.

The Noctambule required her to write her name on a tablet and swear never to reveal this incident. She did so and he touched her shoulder with his ring. He had wandered the earth for 6,000 years, he said, and she was only one of five women to whom he had ever offered this choice and she would be the last. The others: Semiramis, Helen of Troy, Cleopatra, and Diane de Poitiers. Because Ninon chose eternal beauty, he said, she would always be young, charming, healthy and she would conquer any heart she desired. He said he would return when she had three days left to live, and then he disappeared, leaving only a faint whiff of sulfur.

Perhaps this story is true? One sour critic claimed that it was made up by a certain abbot who drank too much and who was infatuated with Ninon, but what did he know?

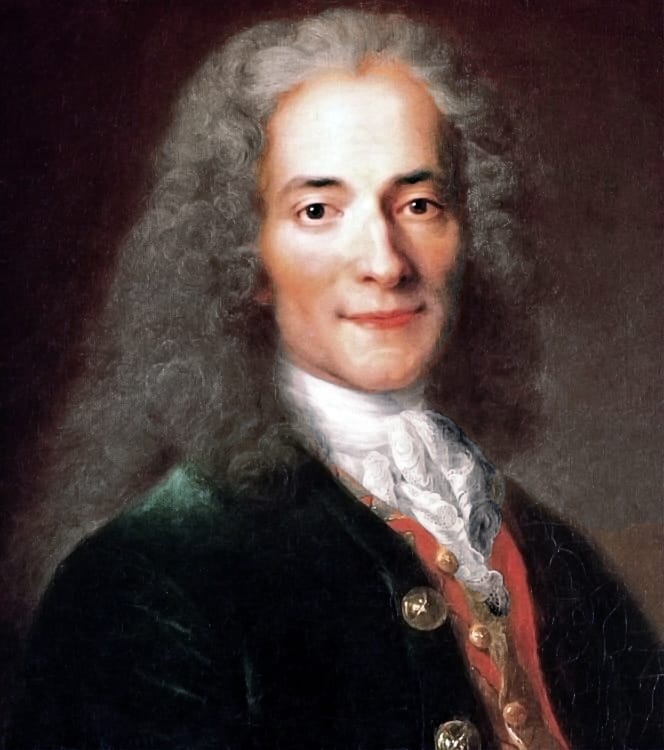

The courtesan Ninon de Lenclos is virtually unknown in English encyclopedias and dictionaries, yet she was one of the most influential figures in 17th century France and it was Voltaire himself who snottily observed, “If this mania continues, we shall soon have as many Histories of Ninon as of Louis XIV.” Curiously, English and American biographers, both male and female, did take a keen interest in her in the early 20th century: Enchanters of Men by Ethel Colburn Mayne (1909) and The Immortal Ninon by Cecil Austin (1927), to name but two. But after that the veil of silence falls once again, aside from Edgar Cohen’s Mademoiselle Libertine (1970). Only after 2000 did more books appear that give her the respect she has long deserved.

Women dominated French cultural life in the 17th century, to a degree that may seem surprising today. It was French women intellectuals who renewed the traditions of the medieval age and the Renaissance, setting the style for the centuries that followed with their invention of the salon, possibly the most significant development in the rising importance of privacy and the bourgeois arts. Ninon herself was born in 1620 to a middle class family in the fashionable Marais district in Paris under the name Anne de Lenclos, but throughout her life she was better known as Ninon. She died more than 85 years later in 1705, by which time she was considered a national treasure. Perhaps the fact that she has been ignored in English-language histories is attributable to sexism and chauvinism in that a courtesan would never be considered a national treasure in England or the United States?

The question is this: do the Noctambule’s choices still hold good today? What do women want? Which gift should they choose today: power, riches and fame, or beauty, or now can they have it all?

POWER

On Its Virtues

As a young woman without a dowry, Ninon had four obvious choices: to marry, to join the Church, to become a governess, or become a prostitute. Of course she chose the last and least satisfactory of these -- prostitution – which is why we must open with a cautionary tale.

Ninon had a son by one of her many lovers. But the father raised his son without him knowing whom his true mother was, to protect him from the shame of it. When the young man finally met Ninon, who must have been in her sixties by then, he fell desperately in love with her. Though she had promised his father never to reveal her identity, in an effort to calm her son’s passion, Ninon confessed the truth to him, and it had disastrous consequences. He went out the back of her house and committed suicide, for he could see that their love would never be consummated. So you see, not only did Ninon not keep her word, these were the consequences of not marrying to protect one’s children and one’s reputation. By all means have affairs, but do not forgo marriage and do not think of yourself all the time.

By way of contrast, consider the case of Ninon’s contemporary, Madame de Maintenon. She was first the mistress and then, from 1684, the wife of Louis XIV, the Sun King, a much smarter ascent up the social ladder.

Maintenon also may have received a visit from the Noctambule, though history does not record this, for she was more discreet. But it appears that she chose power, which is, in the end, all that really counts. If you are a woman, the key to gaining power is, and always will be, through marrying a rich man.

Maintenon’s career illustrates this point: early in her life she married one of those rich men and educated herself in her husband’s salon. Upon finding herself a widow, albeit with a pension, she faced Ninon’s choices: nun, governess or prostitute. She didn’t particularly like men and she wasn’t yet ready for the nunnery, so she chose to become a governess. Luckily she landed a job with the royal family, looking after Louis XIV’s six bastard children – in secret. Thus began her remarkable upward climb at the palace of Versailles.

Maintenon’s marriage to Louis XIV was considered a “morganatic” marriage. This referred to a marriage between a man of very high rank and a woman of lower rank, where the woman kept her lower rank. It meant that any children they had would not inherit their wealth or be considered in line for the throne.

Through her marriage to the King, Madame de Maintenon was granted the power to make an impact on society and she acted upon it, moving against the heretic Huguenots and the flourishing trade in prostitution. In these actions, she sought to reimpose a necessary order upon the anarchy breaking out all over France. It was not religious or social intolerance; she was born a Protestant and she came from the lower classes. Indeed she identified with the poor and she could sympathize with the spiritually lost. Only those who believed in chaos opposed her desire for restoring law and order. Maintenon understood at a profoundly personal level how lives, like countries, can spin out of control. Religious fanatics seemed to be everywhere, advocating this Reformation or that Counter-Reformation, on a rampage, burning women at the stake as witches. Even Maintenon thought they went too far. She fully supported Louis’ crackdown to bring an end to it.

On more personal level, she led by example, dedicating her energies to founding St. Cyr, a fashionable Paris girls school which took in only girls from poor but noble families. It quickly became a successful salon in its own right, offering a way out of the sexual temptations placed in front of young girls. Maintenon was forced to impose strict order eventually, but she did not consider herself prudish; she fully understood Aphrodite’s appeal to women. She even accepted that prostitution was at times the lesser of two evils. When the city authorities used prostitutes in the fight against homosexuality, she begrudgingly accepted it. Most of the houses of prostitution had been closed in the previous century and now there was a real fear that heterosexual marriage could wane because boy love seemed to be so prevalent. Many prostitutes, female and male, operated independently and it had become a lot more dangerous. Some trailed around Europe after armies and they became every bit as mercenary as the soldiers they solicited. Others set up shop in the suburbs.

What saved Ninon was that the courtesan emerged as a better class of prostitute who could wear fine clothes and keep a nice house, who could chase after married men and often keep them, and who worked in secret. (The word “courtesan” is simply the original feminine form of “courtier.”) Generally older women ran these business enterprises, mothers who were once courtesans themselves, and a girl could make a good living. Not that the neighbors were happy about this. Respectable working class and middle class families began complaining constantly to the authorities about the Ninons in their neighborhood and the authorities were obliged to hire many more policemen to cope with it. More than once Ninon had to flee to a powerful protector when things got too hot. Things could get even worse. In Italy there was the threat of a trentuna ("thirty-one" = gang rape) arranged in retaliation by powerful men.

Maintenon urged Ninon to straighten out her own life before it was too late, inviting her to live with her at Versailles. Together they could have established rules for women to live by and have a significant impact on society. The form of power that Ninon specialized in – the power over men’s sexual imaginations as much as their bodies – did not teach the importance of living up to one’s responsibilities in life and ensuring the protection of family values. In the end, Ninon was a hopeless case: she was always more interested in men than in women – and many men at that. There was nothing Maintenon could do for her.

RICHES AND FAME

On Their Virtues

Some would say that the second option, riches and fame, is the least attractive of the three. Who wants to be rich and famous if no one is afraid of you and no one is attracted to you? Well, who cares? You can buy the company of the powerful and the beautiful. Sex has always been for sale.

Ninon certainly understood that. In her earlier years, her love life was keenly scrutinized and there was many a Right Bank conversation about the exact sequence of her lovers – this was a matter of great interest in the City of Love. Only later did she get herself organized, dividing her men into the payers, the martyrs, and the favored. It was the last group who made it into the bedroom. She never did become as rich as some of her clients but she did become famous (or infamous) for her salon.

Ninon’s salon at 28 rue des Tournelles in the Marais soon became the place to be for aspiring men about town and it was never boring. According to the memorist, the Duke de Saint-Simon, the word that summed up Ninon and her salon was “integrity” – no cards or loud laughter, no arguments or discussions about religion or politics. Ninon set the tone with her lightness of touch and her appreciation for all forms of art and culture, always spiced with wit and music (she played the lute very well). She was not a snob either. Although her salon was initially all male, in later life it attracted women from both the aristocracy and the middle class who wanted to learn how to live their lives as successfully – intellectually and sensually – as she had done and mothers introduced their children there before they were turned loose in society. Ninon was influenced by Montaigne’s ideas of political moderation and she knew and practiced Epicureanism, the honorable pursuit of pleasure. At her own salon she was protected by her “birds” – intellectuals like la Fontaine and la Rochefoucauld, some of whom got to sleep with her. She tended to be faithful in short bursts. All this made her a perfect target for local preachers who railed against decadence and immorality, yet she was a target more for her free-thinking and intellectualism than for her libertinism.

Ninon in her heyday became the leading critic of the arts and literature. Molière observed of her: “She has the keenest sense of the absurd of anyone I know.” Some would say there is nothing inherently superior about someone who writes their ideas down for posterity (like Molière) over someone for whom letter-writing and stimulating conversation are equally important (like Ninon). We can get a glimpse of Ninon’s intellectualism in her letters, for example the fine series to the Marquis de Sévigné, the son of Madame de Sévigné, on the subject of how to capture a lover. The inevitable happened of course: the Marquis fell in love with Ninon instead.

However, we don’t want to praise Ninon too highly since she was still sleeping with practically anyone she pleased, including monks and priests, well into her eighties! Indeed, if we are looking for role models, Madame de Sévigné herself offers a preferable alternative to the path taken by Ninon. Isn’t it better for a woman to marry, in the hope that her husband will die young, leaving her all the money, as happened to Madame de Sévigné? By not marrying, Ninon achieved little more than any dilettante. She deluded herself if she thought she could ever change society on the basis of charm and wit alone. She also failed for posterity’s sake, for what great works of art remain as a testament to her genius? What aristocratic title and property did she ever attain? None. What was the nature of her fame? As a courtesan? She barely rates in the history books.

BEAUTY

A Curious Concept

Ideas about beauty change through time. Consider the lithographs of Ninon de Lenclos and wonder why men and women found her so beautiful. She belonged to another age when aesthetic ideals were very different. But if her beauty was not resistant to time, then she did age gracefully at least.

One of Ninon’s critics once remarked, “She never had much beauty, but, above all, she had charm,” and one of her lovers said, “Her mind is more charming than her face.” Was charm the gift of the Noctambule? Like many women today, Ninon was alluring, seductive, sexy. Pure beauty is another matter: men usually find it somewhat remote, even intimidating. Helen of Troy was the best looking woman in ancient Greece but hers was a chilly beauty; men were only besotted with her until they met the woman underneath. People wondered whether there was a life of the mind behind the face and the body that launched a thousand ships. If there was, she failed to convince anyone beyond Paris.

Ninon chose beauty because it gets you the other important things in life – power, respect, riches, fame – it is just a means to an end. Prostitution is the same: women do not “fall” into it because of a failed love affair or broken heart. Neither do they do so because they are venal and unredeemable. They do so because the lifestyle can offer financial and emotional independence beyond what men are otherwise prepared to grant. The courtesan was a rebel before she was a fallen woman. Rightly the courtesan decided to live her life like a man, not as a man, for what is a man of the church or a man of public life but a whore? Ninon understood this at an early age. When she was 20 she wrote: “I notice that the most frivolous things are charged up to the account of women, and that men have reserved to themselves the right to all the essential qualities; from this moment I will be a man.”

Women become courtesans because they have friends who are doing it, full time or part time. For the successful courtesan, to have an attachment to a richer client-lover means clothes, an apartment, furniture, a carriage and horses, entertainment. Of course you must use your beauty to add a dimension of danger, intimidate men a little, reel them in. But how do you appeal to men? Not just by being a clothes horse. Beauty always depends on the intellect. Ninon, like other beautiful and intelligent women, enjoyed friendship and good conversation more than sex or seduction. She had many lovers over the years and she enjoyed sex, but her seductions were intellectual as much as physical and this is one of the key distinctions between a courtesan and a regular prostitute, which is not to say that all courtesans were intelligent company or that they had the freedom to live in the way they chose, but courtesans were able to ascend to levels of society that prostitutes found closed off.

By way of contrast, Madame de Maintenon paid too high a price for her power, for she constantly had to guard against losing Louis’ favor and she was never happy. Her influence became increasingly more religious, driving off the intellectuals and the libertines. Many considered her a bigot and held her responsible for the catastrophe of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, and whether that was really Louis’ doing, she did not stand in his way. In a dialogue by Voltaire, he has her say to Ninon, “It was decreed I must be a prude” and in the end that is what she was. Ninon herself once said of Maintenon that she was “too awkward for love.” Madame de Sévigné hardly represents a better alternative: to hope your rich husband will die young can turn into an impossible trap, where thoughts of murder intrude. It galled Sévigné deeply that her son became enraptured with Ninon.

Ninon was not interested in remaining attached to anyone for too long; she liked interesting and good-looking men but there were always others on the horizon. “Men lose more conquests by their own awkwardness than by any virtue in the woman,” she once wrote. “A woman’s resistance is no proof of her virtue; it is much more likely to be a proof of her experience.” After all, love is transitory, an illusion of the senses.

So far as the nasty allegations go, the story of her son committing suicide was made up by a hack writer. Ninon never had any children, which didn’t stop this story from making its way into her biographies. So far as going to bed with randy churchmen when she was in her eighties, Ninon was past worrying about that by then. It is true that monks and priests have made for very popular sexual partners because they are safe, discreet, and accessible. But this story about Ninon only reflects a certain churchman’s wishful thinking. Legends have always developed around beautiful women like Ninon because the inadequate men and women who dream them up were never privileged to share beds like Ninon’s. Beauty was clearly the best choice even if, like the others, it did not last.

THE ENLIGHTENMENT BEGINS

You will remember that the Noctambule intended to return to claim Ninon’s immortal soul. He did show up three days before she died, but he went away empty-handed because Ninon, an agnostic, apparently did not believe she had a soul to lose, and so had nothing to give him. This deathbed scene in 1705 marks the official beginning of the revolution known as the Enlightenment.

Ninon’s fable of the Noctambule is interesting because it reflected man’s attempt to explain women not as goddesses from another world but as enchantresses whose beauty just seemed divine and magical, perhaps even diabolical. The story keys into Christian and Romantic, not Classical, sexual fables. The Noctambule is of course Mephistopheles, the Devil. Let us say that the Noctambule really did appear before her. She chose beauty because she knew perfectly well that if she was beautiful, then it had nothing to do with any supernatural explanation he could come up with, however tempting that view was to others. The world of science was coming.

As she lay dying, it was clear she had lost her beauty, even if she still had her extraordinary femininity. Voltaire was introduced to her back then – he was 11 and she was more than 80 – and the great philosopher commented (much later) that “Mlle. Lenclos had all the ugliest signs of old age in her face, and her mind was that of an ascetic philosopher.” So much for eternal beauty. But he made this snotty comment about a woman who had generously left a lot of money in her will for him to buy books, and one suspects he was just being facetious to cover his own respect for Ninon’s intellect. How sharp the old lady was. Even Voltaire was only 11-years-old once.

Faust

A century later, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe would be drawn to the story in his masterpiece Faust (Part I was published in 1808). Starring in the Ninon role is Faust, who has choices over his destiny, while the Noctambule is played by Mephistopheles. Goethe had other sources of course. As a boy he was impressed by puppet shows in which Faust and the Devil sparred in an eternal struggle over faith and man’s salvation. Goethe, like many before or since, experienced the sensation that if man could defeat the Devil then he could also stand up to God. Goethe was familiar too with one Georg Faust, who had made a career for himself by boasting that he was a necromancer, just as he was familiar with his contemporary Martin Luther, the true Faust figure of that century. Indeed it is not a coincidence that Goethe set Faust's home in Luther's Wittenberg!

Goethe’s Faust was as racy for its time as anything ever written. He arranges for Helen of Troy to be transported through time and space for Faust’s sexual pleasure and they even have a love child together. Helen is romanticized as the perfect woman, Greek beauty and harmony wrapped up in the one superb body. But Goethe was not really that interested in Helen. He was more interested in why there had to be all that killing at Troy in the first place over a woman! Goethe correctly surmised that the gods were behind it, since there was no other satisfactory explanation. He also thought it fair that Faust be let off the hook in his bargain with Mephistopheles, for why should Faust surrender his soul? This infuriated the religious authorities and other pompous German writers of the time who hated happy endings, but it revealed Goethe as a child of the Enlightenment. There were reasons for this.

Goethe had made a much-written-about trip to Italy in the late 1780s, when he was approaching his 40th year. That trip had liberated him to be an agnostic and an erotic materialist and it extricated him from the dead end of idealizing women who were unavailable – women like Charlotte von Stein. It was at this time that he chose to live with, and he later married, a young German woman from the working class named Christiane Vulpius, repeating what Martin Luther (and Rousseau in France) had done before him. While Christiane could never really share fully in his intellectual interests, clearly their erotic attraction to each other was enhanced by their differences, socially and intellectually. Goethe’s erotic epigrams from this time are full of nudity, erections, masturbation and other steamy subjects. Few academics ever look at that aspect of Goethe’s writing, just as they ignore Christiane, although some have claimed to detect a whiff of homosexuality there. Rich women snubbed him after that, but Goethe knew that love, such as it is, was more important than the artificial barriers of class, age, culture and religion, and that loyalty freely given is what binds relationships together. He understood that women were at least the equals of men and in some ways superior and, because he believed this, he publicly promoted the careers of many German women intellectuals.

Goethe celebrated women in his concept of the Eternal Feminine spirit that embodies all the women that Faust encounters – not just Helen but also the unpretentious and tragic Gretchen (aka Margarete), who somewhat resembles Christiane and who has inspired countless paintings. And that's because Goethe goes full melodrama with Gretchen, who makes a lot of terrible mistakes. She is an "innocent": she becomes pregnant to Faust, her mother and brother end up dead, and then, ashamed, she drowns her “illegitimate” child and accepts the death penalty, rejects Faust and still goes to Heaven! It is this generous spirit - Goethe's - that Ninon embodied; it is the spirit that would become the basis for the growing sense of the privacy of the feminine self in the so-called bourgeois century, the 19th century.

Intellectuals focus their attentions on the anxieties of unrequited or ideal love, and Goethe wrote his fair share earlier in his life. But the lesson we learn from Ninon’s life, and what Goethe learned from Christiane, is that when we make a judgment on someone’s life, what truly matters is how we live our own lives. It matters how we use the choices available to us, and how we make choices available to others. What does not matter is adherence to prevailing social, political, religious or academic orthodoxy, which doomed Gretchen.

THE JUDGMENT OF PARIS

When Paris was forced to choose between those three gorgeous goddesses back in ancient times, he could have had political power from Hera, or warlike prowess from Athena, or he could have had the most beautiful woman in the world from Aphrodite. As we know, he chose Aphrodite.

Despite what the Iliad or the movie Troy would have you believe, Paris was not only extremely good-looking, he was also an honorable man, which is why the goddesses chose him in the first place. For his part, he chose Aphrodite because she seemed like the least dangerous option. Little did he suspect when he was “rewarded” with the most beautiful woman in the world. As with anything to do with the gods, she was a flawed gift, for she turned out to be Helen of Troy and she was already married. As was he, of course, for both had had arranged marriages imposed on them. And though Helen was undeniably stunning looking, she was not much of a match in intelligence. Rather vain and frivolous actually. If her beauty was immortal and eternal, it was all on the surface, a harmony of the parts. She was, in a word, superficial.

And who is to say that Paris truly had a choice in the first place? If indeed he had had a choice, would he have chosen a married woman and a vacuous one at that?

Once this series of unfortunate events began to unfold, however, her husband Menelaus wanted revenge upon Paris’ family. This was understandable perhaps, not because he was jealous, but because Helen was his property. It led directly to the Trojan wars and the eventual downfall of the House of Atreides. Helen was right in one matter at least: she blamed Aphrodite for the affair with Paris, claiming she had always wanted to return to her husband. For Paris’ own part, he was opposed to the war all along, believing it solved nothing. He was an idealist, a rebel; he only wanted to please everyone. He ended up pleasing no one. The gifts of the gods were a curse. They had made him participate in their charade, hurting everyone in the process. It seemed to Paris that humans were just as vain as the gods, for all they ever needed for a war was some petty excuse. That was all Agamemnon was interested in.

Paris has since been dismissed as a lightweight seducer, pushed to sidestage by the noisy, flashy Achilles, the heroic Hector and the “wily” Odysseus. He also has had to endure the idea that The Judgment of Paris qualified as a male fantasy in which the man could have had any woman he wanted and the women were to be blamed for everything. It was all a lie. Paris liked women. It was the gods – male and female – who were to blame for making us their playthings. He would not be the last to confront them.