The Whore's Revenge

The One Time Casanova Came to Grief

The One Time Casanova Came to Grief

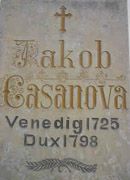

Once upon a time there really was a man named Giacomo Casanova. Born in Venice in 1725 and dead in 1798, for the better part of the century he seduced amorous nuns, virgins (some as young as 13), innumerable married women, two sisters at the same time, a castrato (“he” turned out to be a “she”), he traveled with a lesbian companion, he escaped from the dreaded Leads prison in Venice, he displayed great skill in the magic arts and he set new standards in libertinism. That is just the half of it.

Jacques Casanova de Seingalt as he called himself in his memoirs was tall, good looking with bright dark eyes and a beaked nose. He was, you might say, the Valentino of his day. He was also an intellectual who could hold his own against Voltaire and he once wrote: “Nothing on earth has ever had such domination over me as a beautiful woman’s face, even if she is only a child. Beauty, I have been told, has that power.” He goes on to argue, quite shrewdly, that perfect beauty does not exist because beauty is in itself just a convention. “So what has always exercised an absolute sway over me is the living beauty of a woman, but that beauty as it exists in her face. That is where the spell resides...” Casanova once encountered one of those beautiful faces in London and he came to grief with her. This is the story of Casanova and the courtesan. For once in his life he lost control and assaulted a young woman. The question is: if he beat her up, was he justified? Is violence ever justified between a man and a woman? And if it was, was there something else at stake here?

THE EVIDENCE

Marieanne Genevieve de Charpillon was 18 years old when she met Casanova in September of 1763. She was at the house of a mutual acquaintance, escorted there by one of her great aunts. Casanova must have been about 38 at the time. She knew of his reputation as an experienced seducer and libertine, but he was now approaching middle age. Even so, she was fascinated by him. They had met once before in Paris when she was 13, but no doubt he had forgotten it because she hadn’t gone to bed with him. This time they flirted as the occasion demanded and she teasingly warned him that he would fall in love with her if this persisted.

She then took the liberty of inviting him to tea at her house, but he said he found the time inconvenient because he had an engagement at Lord Pembroke’s. Since Marieanne knew Pembroke, she invited herself there instead. This is an acceptable ruse in the game of love, but it irritated Casanova. He makes a snide remark about it in his memoirs, “You think you can make anyone you choose fall in love with you, and then propose to play the tyrant? The scheme is monstrous, and it is a pity you do not let men see more plainly the kind of woman you are.” Was this an overreaction written in hindsight or was it a tease? At the time Marieanne laughed it off as mere ill humor.

For she knew Casanova was attracted to her. His memoirs are very revealing: “Her hair was of a beautiful chestnut color and of astonishing length and luxuriance; her blue eyes had a languor natural to their shade and all the brilliance of a woman of Andalusia; her skin, which had the tints of the rose, was of dazzling fairness, and her tall figure was almost as finely modeled as that of Pauline. Her breasts, perhaps, were rather small, but of a perfect mould; she had white, plump, tiny hands together with the prettiest feet and that proud and graceful carriage which gives charm to the most ordinary woman.” Yet he seemed to expect Marieanne to fall at his feet and beg to be another conquest. When she did not, he revealed his habitual bitterness: if she was extraordinarily beautiful, then “nature was pleased to lie.” The same might have been said of Casanova himself!

They met again several more times and Casanova made sure she noticed he was paying for everything. Still, she did not think it was time to engage in intimate relations, at least until after he had been introduced to her family. Several times he forced himself upon her in public but Marieanne was as “supple and lithe as a snake,” to use his words, and she managed to evade him. But he had the cheek to visit her at home unannounced one day while she was in the bath. The voyeur got a view of her naked back and then practically all the rest of her when she turned to ask her aunt, for she thought it was her, for a towel. She barely got her hands in front of her body to shield herself from his gaze and his deception put her out greatly. She angrily demanded that he leave at once, and he must have felt a trifle guilty because on the way out he contributed to her aunt’s investment fund. The aunt was, you see, promoting a fund for the development of an elixir of life that the family hoped would become their principal business enterprise.

When she met Casanova again, as was inevitable in such a small social circle, he decided to treat her like a common prostitute whereas she felt only love for him. She asked him, “Is it true you told Goudar to offer my mother a hundred guineas for me?” He retorted, “Is it not enough?” She was furious: “Have you any right to insult me?” This degenerated into a sordid argument about money and she finished up spitting out “You can come to our house, but keep your despicable money. Conquer my love as an honest, straightforward lover, not as a brute, for you must believe it now, I love you.” Maybe she overdid it because he muttered something nasty about her being a born actress.

Still she kept him at bay. One night when they were alone and he thought he was in for his reward, she knew he would become more aggressive. She therefore changed into a tight negligée and sat with her knees up to her chin, her arms crossed, her head on her knees. Try as he might over the next three hours he could not unravel her. He roughed her up, he hit her and tried to strangle her, and the negligée ended up in shreds but there was no sex! Did she tease him unreasonably? Probably. Did she feel a bit mean about it at the time? Yes, but she felt that he should win her love. Was that so unreasonable?

Marieanne’s mother was very upset when she was told of this brutal behavior and she threatened Casanova with legal action. Anyone could see that Marieanne was covered with bruises. Marieanne went around to Casanova’s house to show him the bruises on her legs and her neck and shoulders, but he practically raped her again. Her bruises only seemed to encourage him! When he calmed down, he agreed to behave properly and set her up in a house of her own and it is only fair to say that he did this promptly. They also settled the assault charges out of court. A pleasant evening together ensued but again, as things progressed to the intimate stage, they once more got into a fight. Perhaps she hugged him around the neck too tightly? He became too aggressive, too Italian, and he let his emotions run amok. When he had worked himself into a complete state this time, he beat her up properly. He hit her on the head several times and then kicked her really hard, sending her sprawling across the floor. She threw things at him and screamed blue murder until the landlord came up to find out what was going on. He found Marieanne with her nose bleeding violently all over the carpet. At least she knew she got a few good blows in, but their experiment in living together was over.

You would think that would have been the end of it, but Marieanne’s mother unwisely invited Casanova over to pay his respects and to ensure there was no ill feeling. Once he had his foot in the door again, he kept coming back, bribing her with gifts. Each time she resolved never to utter a word to him the whole time he was there but how long could she keep that up? As you can imagine, she began to feel lonely, under siege. At one point she let him hold her and she found herself weeping uncontrollably. He asked her whether she would ever feel differently and she replied truthfully, ‘No.” To her relief he departed immediately and stayed away for weeks.

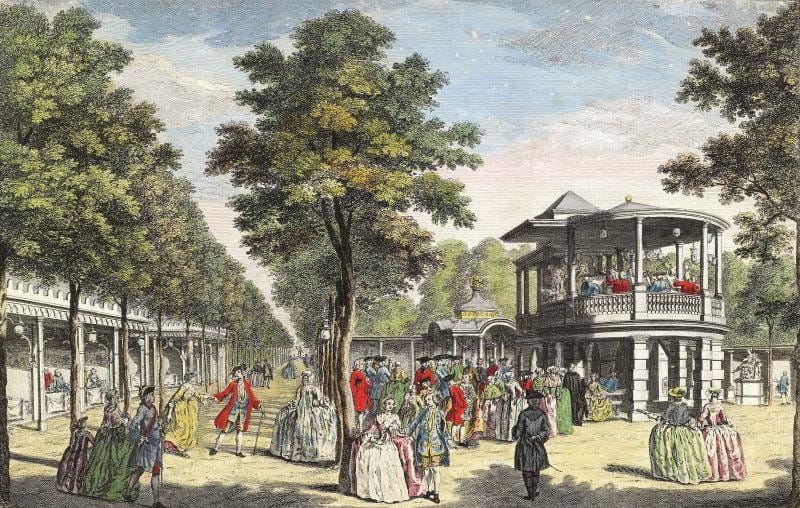

Of course, they had to bump into each other again, and when they did, he was agreeable and sociable. She even momentarily considered the idea of resuming their relationship so long as he resolved never to force his attentions on her. As they strolled in Vauxhall Gardens she pulled him down on the grass beside her and they caressed each other affectionately. But he took this as an invitation to have sexual relations right there in the gardens in full public view so she had to put him off by promising to come to him that night. He did not believe her and pulled out a small knife and pressed it against her throat, threatening to kill her. She pointed out that if he had her there on the grass she would just lie prostrate until people came to find her and that she would file charges. Thank god he became shocked by his own temptation to violence and left off.

At any rate he came around to Marieanne’s house to argue about some money her family owed him and he caught her half-naked on the sofa with a good-looking young hairdresser that she had been seeing, though there was really nothing in it. She found out later that Casanova was outside watching the house for hours and when the door opened he had slipped inside and launched a storm of abuse upon her. He caned the little hairdresser and smashed the presents he himself had given her, plus most of the furniture while he was at it. Marieanne fled the house. She was told he offered to pay for the damages and that he was upset on hearing that she had become gravely ill. There were even rumors that he considered suicide but she spotted him out in public several days later so she doubted he was serious about it. Such men seldom are.

What really outraged her family after all this was that he then sued for money that he said they owed him -- obviously for spite. They counter-sued for trying to “disfigure a young and pretty girl” as the law books put it, but he got off and he got his money. What else would you expect from the English courts? They are only there to look after the interests of the rich.

Casanova was never a suitable marriage opportunity for Marieanne. She was young and still relatively innocent while Casanova was a treacherous libertine. She could make a better catch. He was not an especially generous lover and he was not even an aristocrat like he pretended. She tried not to lower herself to his level but she ended up getting caught in his vicious circle. Beware being turned into a kept mistress. He beat her all right and he tried to take advantage of her. She deserved better than that.

THE CASE FOR THE PROSECUTION

The Lord Mayor of London, John Wilkes, would be the man to defend Marieanne Genevieve de Charpillon against the slanderous accusations of Casanova. During the events of 1763, when Casanova was in London, Wilkes was not yet Mayor. He was in fact abroad, kicked out of Parliament for his “seditious writings.” Settling in Paris, he occupied his time by studying that city’s sexual wildlife, and the court of Louis XV was quite the place to see it. He only had to visit the Louvre, Versailles, Fontainbleau to come to the conclusion that the French needed a Revolution over there.

A decade or so later, he would develop a romantic interest in Miss Charpillon and she became his mistress. A sweet girl, with nice breasts, whatever Mr. Casanova had to say about them. He felt they were well suited, and if he was as ugly as he was charming, then Charpillon was as beautiful as she was dangerous. It was Beauty and the Beast.

Wilkes and the great Casanova shared certain attributes. They both favored dalliances of short term expediency and damn the matrimonial entanglements. They were both as interested in having a good time with prostitutes as in extending the freedom of the press and by God, both activities were related in the end!

Wilkes, on the other hand, was under no illusions about the real Miss Charpillon. He knew she was born in Paris or eastern France after her family had been kicked out of Switzerland in 1739 for running a famous brothel in Berne. They resumed the family business in Paris and then, after 1759, in London. The family consisted of her grandmother, Catherine Brunner, who ran things; Brunner’s two sisters, one of whom had the sideline in the immortality business selling the elixir of life; Miss Charpillon’s mother; and Miss Charpillon herself. Wilkes provided for all of them, something Casanova had failed to do. That was his first mistake. A girl has to make a living. Her family’s notorious reputation – which was probably worse than Wilkes’ – had prevented her from marrying into the aristocracy or new money. But she suited Wilkes, although she did get to be damnably expensive. It seemed to Wilkes that a mistress could be defined as the attempt to duplicate, as well as one could, a husband-wife relationship, but with none of the obligations. A prostitute is the same thing except that she is exclusively for sexual purposes and you don’t have to wake up to her bad breath every morning. So, clearly by this definition Miss Charpillon was his mistress. But Wilkes felt that Casanova did not appreciate this difference when he encountered Charpillon 10 years earlier. What had he wanted from her that he treated her like a prostitute? That had been his second mistake. He had only been interested in conquest.

But there were other reasons. Casanova was a man of Venice, a foreigner, and London was bad for him because he simply didn’t understand its ways and means, its passions and privacies. The poor fellow… Miss Charpillon thrust the dagger unerringly into his breast and he did not know how to take it out, for in his heart he was an incurable romantic. This was his third mistake: it hurt his vanity that she wasn’t really interested in him and so he was resentful and he beat her up. This was his fourth and biggest mistake. Violence is not acceptable in civilized society unless you get away with it. He lost the game and eventually had to flee England over some bad debts, contracting another dose of gonorrhea on his way out.

In all fairness, if Casanova was not justified in beating her up then neither was she justified in leading him on like that either. In paying no heed to the proper rules of engagement they were both equally foolish. But this case is not about defending Miss Charpillon; it is about indicting Casanova. Of course he was not a scoundrel so much as a silly sentimentalist. His skill, it seemed to Wilkes, lay in his Italian style of flirtation: firing off Cupid’s dart to catch the maiden’s eye, exulting in the perfect hit, that moment in the exchange of glances. But many a foolish fancy has been built on as flimsy an experience and that was Casanova’s trademark. He seems to have fallen in love at the drop of a hat with most women and he was off into raptures in his own private world. Wilkes knew instinctively that that was not a good way to handle a woman like Miss Charpillon for she would exploit such a situation mercilessly. Poor Casanova made the mistake of believing that sex can be a romantic exchange when it is nothing of the kind. Consequently he seemed to find English orgies rather mechanical and boring, as if he expected that next time things would be different. But sex is a temporary loosening of all restraint, an expenditure of sexual energy. Perhaps the English libertines were a cynical crowd, only one step removed from the puritans, with their glittering eyes masking their sexual disgust, but they were never sentimental. In the coming era, Wilkes felt, there would be no place for a romantic narcissist like Casanova.

The encounter with la Charpillon was a turning point in Casanova’s life. Things would never be the same for him again, not because he hadn’t missed on going to bed with women in the past, but because of the particular virulence of this encounter. At a certain season in one’s life, one’s mortality becomes all too apparent. If Casanova was an adventurer and trickster himself, here he had been outwitted by a woman less than half his age. It irritated him all the more that she seemed to have perfect judgment in knowing where to hurt him, not because she was a woman, but because it was inconceivable to him that so beautiful a face could conceal a mind so treacherous and so dangerous. More fool him.

THE CASE FOR THE DEFENSE

La Charpillon’s name as we know it from Casanova has come to signify a manipulative bitch, a harpy, and let us not pretend these women don’t exist. When Casanova met his nemesis those many years ago, the first phase of his life did come to an end. The defense does not deny this. Apocalypse. Catastrophe. The great lover had come to grief. But though she seemed to be a coquette, she really was Casanova’s complete opposite. Flirtatious at first, she revealed herself to be a woman who did not enjoy sex, who instead used sex as a means to an end, an economic transaction. For Casanova, money was a means to obtain sex, while for la Charpillon, sex was the means to obtain money.

The true coquette asserts her place in the world, that she exists, that she needs to be allowed for, paid for, not ignored and she gains pleasure from that. But la Charpillon was a businesswoman, not a lover – she was in it for the money, not the love. She was death to the romantic game-playing through which Casanova hoped to avoid coming to his metaphysical rest. She was a vampire, a prototype for the next century. Charpillon was a true cynic, while he was a true romantic. They were opposites: a cynic believes in nothing except money; a romantic believes in everything except money.

So which approach to life do you choose for yourself: cynic or romantic? Havelock Ellis, the English sexologist, was a romantic. In 1899 he published Affirmations, a collection of essays in praise of life’s great “affirmers,” including Casanova, Nietzsche and St. Francis. Interesting choices… Ellis decided that Casanova may have had his faults but he was a magnificent piece of machinery and he lived life to its fullest potential. Ellis gave intellectual legitimacy to sexual liberation during the 1890’s right through to the 1920’s. Indeed his defense of Casanova said much about his ability to see past stereotypes and hypocrisy. On the other hand, it is questionable whether he ever experienced sexual intercourse himself, for most of his life he was married to a lesbian, Edith, and his chief sexual pleasure appears to have come from “urolagnia,” urinating during sexual activity – meaning she did it, not him. This makes him a “fountainist” and a soulmate of Ulysses’ Leopold Bloom. On the other hand, it does not invalidate his defense, even if envy surely played a role here? In the wake of the Oscar Wilde trial on 1895, Ellis was the first to defend homosexual and lesbian (“inverted”) identities in a thoughtful and scholarly way and he gave key moral support to the first lesbian novel, the controversial The Well of Loneliness, by Radclyffe Hall, in 1928-29. It was promptly banned for decades, but Casanova would have approved of it.

Viennese writer Stefan Zweig also chimed in. He published his biography of Casanova, Stendhal and Tolstoy, Adepts in Self-Portraiture, in 1928 (1930 in English). Zweig initially seems to be in the mood to destroy Casanova - that “famous charlatan,” that “parasite” on women. But he goes on to reveal this as irony: “What makes Casanova a genius is not the way in which he tells the story of his life, but the way in which he has lived it.” This places the episode with la Charpillon in the right perspective. It was not some terrible humiliation on which one may judge the success or failure of a man’s life - that is how Arthur Schnitzler had cynically portrayed it in Casanova's Homecoming (1918). It was merely a few months at a turning point in his life when he suffered a few setbacks and don’t we all? If he roughed her up a bit, then she roughed him up too, and who is to say which was the more aggrieved party? There are those who think any kind of physicality between partners is abuse, yet most of the population indulges in it to varying degrees, and in the end it is the totality of a life that matters. Casanova was a true prince among men and if la Charpillon was no princess, she also achieved what no one else achieved – the humiliation of the world’s greatest lover.

Over the decades, and especially once his memoirs were translated into English, Casanova gradually came back into fashion. Reading the memoirs, it is apparent that he was never particularly pompous, jealous or spiteful. It is quite an extraordinary book! There are no rapes, not even of Miss Charpillon. Casanova wanted only to be surrounded by beauty and sensuality and he was disappointed only when life failed to live up to his expectations. Casanova found women too interesting as a species to be cynical about them and it is precisely because he treated women so well that he was successful with them. This is the one fact of his life that must be set before anything else when judging him. Casanova is therefore superior to Don Juan, who was a fictional character, for women thanked Casanova after they made love! Don Juan and Valmont were sadists, who were more interested in degrading women, in destroying beauty. Casanova was able to claim “Four-fifths of my pleasure has always consisted in making women happy.” That is a profound statement, even today.

If Casanova was a romantic it was because he had the good fortune to have experienced true love once in his life, even though he knew it was transitory. The woman in question was Henriette, a beautiful young woman whom he met in his younger days. Her role switching resembles Casanova’s own and perhaps they were both French spies at one time. If she too was a romantic, then she understood the limits of romantic love – after three great months together she left him. She wanted to marry a husband who would remain constant in his sexual attentions and his finances, just as she knew she herself would not remain constant. If Casanova was her true love then she knew equally that he could never be constant either. They were equals. For such lovers the truest form of love is a fantasy you carry throughout your life for your perfect sexual mate that can only be diminished by staying together. Such a love is a Romantic notion. It is also an intellectual and spiritual activity as much as it is a physical one and it is never satisfied. That is its point, although as the years go by, nostalgia sets in too. “Inconstancy in love exists only because of the diversity of faces,” Casanova once wrote. Such diversity, so many choices, it leaves a slight trace of melancholy in his writing as if the waters of Venice had permeated his soul, almost as if he knew his world was being washed away by the French Revolution as he wrote these words.

For all the talk of Casanova’s defeat, the Devil himself could not have improved on Casanova’s revenge on Charpillon: he purchased a parrot that he trained to screech “Miss Charpillon is more infamous than her mother” in French. When everyone got the joke it became the hot topic of conversation in London and even la Charpillon thought it very clever. Her mother and aunts were not so thrilled. They consulted lawyers but were told that the law of slander did not extend to parrots. Charpillon was cleverer. After Lord Grosvenor bought the parrot for her, she wrung its neck. So much for freedom of speech!

THE ELIXIR OF LIFE

The grumpy old ghost of Casanova still haunts the library of the Castle of Dux. The Castle squats in western Bohemia, passing through time like a ship passes through space, the clouds soaring overhead. The ghost has been at war for many years with the vicious little mediocrities employed at the Castle who barge in from time to time to fling insults at him. He has rigged a trap over the door into the library and next time, he plans to flatten them with an avalanche of his heaviest German philosophy books. The minions of his patron, the Count Waldstein, master of the Castle.

Sometimes he is no longer sure who they are. Their clothing has changed, become outlandish. Have more years passed than he knows? Even the servants do not look like servants any more. They always considered Casanova grandiose and pompous; they had no manners, no style. He wrote long ago: “The older I get, the more I feel the destructive effects of old age; and I regret bitterly that I could not rediscover the secret of remaining young and happy for ever. Vain regrets!” But he had discovered one secret – the secret of how to remain alive, even if it had frozen him in his sixties. This was now, he calculated, the summer of 1938. Like Tithonus he felt himself constantly dissolving, then coalescing. It was becoming intolerable. He went outside among the oak trees, knowing he had chosen unwisely: immortality was a curse and he longed for it to end. He had heard from a recent visitor, Sandor Marai, that Germany had marched into Austria some months ago and all the talk now was that Bohemia would be next.

What no one knew at the time of Casanova’s encounter with la Charpillon was that he had destroyed her furniture because he was looking for the elixir of life, which he knew to be hidden somewhere in her house. He had reason to believe the family had stolen it from the Count of Saint Germain when he was in London a few years earlier (at least this was what the Count had told him). For years Casanova had searched for it and now, as an aggrieved investor, he felt he had the moral right to repossess it. All that drama with Marieanne had been merely a distraction; the irritating girl had become an embarrassment. He knew that the family had not composed the elixir themselves; they were businesswomen, not chemists. He also knew the formula was not yet perfect. Indeed he suspected it was the same formula he had once held in his hands many years ago when he was arrested and thrown into the Leads prison. But in those days a quick sip had made him feel ill for days at a time. Had the chemical composition changed over the centuries? Had some important ingredient decayed? Was it a hoax? Now that he had the bottle in his possession again, he had tasted it one more time before leaving London, but again he had fallen ill (in his memoirs Casanova conceals its noxious side effects as gonorrhea).

As soon as he was well enough, he traveled to Paris. This time he knew he had an opportunity and the means to test the elixir but, unfortunately, there was not enough liquid in the bottle to satisfy M. Lavoisier. Too many previous custodians had sampled it and fallen ill – Lucretius, Jesus Christ, Tristan and Iseult. Fortunately they had not discarded the bottle for fear it might actually be worth something. So the only solution was to trace the history of the bottle and its precious contents back in Venice to see if someone could recall the missing ingredient. He knew that both the mysterious figure named the Noctambule and King Solomon were involved somehow, but his inquiries would come up empty in Venice. It was only years later, as he was reading a biography of Ninon de Lenclos that a thought occurred to him: if the Noctambule had been around for thousands of years, then possibly the solution lay back in antiquity. He therefore devoted himself to re-reading the classics and so it was that as he read Plato’s Phaedo he had an epiphany: perhaps Socrates knew more than Plato was revealing. This was not some idle conversation about the immortality of the soul. He concluded that Socrates had drunk the hemlock not to die but to achieve immortality and he had failed. No wonder he had been so fearless; he had thought he could outsmart his enemies. It occurred to Casanova that if life were a paradox, a contradiction, how ironic then that the missing Key of Solomon was, in itself, also a poison. And so, in 1785, Casanova tasted a few drops of hemlock with the elixir and had an enormous and immediate erection. The long awaited alchemical breakthrough had been found. Repeated experiments left him somewhat exhausted, but there was also now a distinct sense of rejuvenation. When he retired to the Castle of Dux, he was convinced he now had the right formula, and as he set sail on his memoirs, he also began to sip on the elixir of life.

Here he was at the close of one century and the dawning of another, hoping to clear his name with you, the reader. He knew his reputation would suffer unless he explained things in his own way and writing was as good a means as any to preserve the spirit of the past. He had chosen to write it in French because he thought it would reach the widest audience. With his skill in the magic arts he was fortunate in being permitted to view something of the future before he would live through it. He knew in advance the fate of his memoirs and it did not give him any satisfaction. After his official death, it would take until 1820 before his inept relatives got around to approaching a German publisher and within a decade an abridged German version would be selling well. But almost immediately a pirated French translation appeared and sold even better. To counter this the German publisher decided to print the original French (between 1826 and 1838), again abridged of course, by an idiot named Laforgue who cut out all the erotic bits and added some unnecessary political commentary and psychological explanations. Such are the twin curses of nationalism and puritanism. But an even greater curse was to be alive to witness such travesties while being unable to do anything about them. The English and Italians, meanwhile, had to do without a translation until the 1880's. Not that they appeared to care.

There was a dramatic surge of interest in the 1920s when a ton of books about Casanova appeared and further translations followed, but with all the risqué bits still cut out. For Casanova this only confirmed that the present was not the revenge of the past upon the present but the revenge of the present upon the past. Civilization did not progress; it regressed. Such conceits the present age lived with!

As Casanova drew level with his ailing biographers, Havelock Ellis and Stefan Zweig, he knew that they too could see the storm clouds steadily gathering above them. The Four Horsemen were on the loose again. There were those who found Ellis a cold fish, with his pasty white nude sunbathing and his strange sexual habits, but there was respect and even affection now that he was dying. Ellis was racing to finish his memoirs before it was too late. Zweig and his wife were now in England, having recently fled Vienna when the Third Reich marched in. Ellis would die the following year, shortly before war broke out; Zweig and his wife would commit suicide in Petropolis, Brazil, during the war. Depressed and homesick they believed humanity had lost sight of its core values as the war took its brutal course. The cynics were in charge again. Marai too would take his own life, alone in San Diego, in 1989.

Casanova would not outlive them. On this day in 1938, he stood under an old oak tree and wondered if he was older than the tree. He thought it must be at least 300 years old. As he put his hand on the rugged gray beard of the dragon beside him, he felt it all dissolve away and momentarily he was gone.

He would not be around to know that his original manuscript would nearly be destroyed in its Leipzig vault by Allied bombers. He would not know that it would be 1960 before the German publishers announced that the complete, unedited memoirs would be issued, this time in French and German. The uncut English language version trickled out between 1966 and 1971, translated rather prosaically by W.R. Trask. The original manuscript is now in Paris in the possession of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Filmmakers would weigh in too: Fellini Casanova, released in 1976, is a scathing and sterile portrait, but it dishonors Fellini rather than Casanova. Literary historians say Casanova embroidered his stories; others ask how one man could have had it so good. But research backs up many of his claims and the issue of reliability or truthfulness misses the point: he successfully lived the spirit of his age and he made no apology for this in his memoirs. They are entertaining and strikingly contemporary in that he is never judgmental or exploitative and he frequently assisted those in need. How many books in any era have a character like his friend the flamboyant lesbian Marcolina?

Casanova, like Voltaire and Goethe, would have argued that academics take their revenge on writers who enjoy sex by damning them to Hell. Literary criticism is not about the fear of emasculation and the castration of men. It is about modern Charpillons, male and female, re-enacting that emasculation on the male heroes they have discovered in literature. The bourgeois university professor is secretly an authoritarian who understands nothing of the true alchemy of the erotic arts. He or she craves stasis and security (“tenure”), whereas Casanova’s life was just the opposite – a series of assignations, of pleasing different women and moving on, of being open to life’s rich potentialities. A slug does not see outside its own garden. Academics are mostly cowards because they are unable or unwilling to defend the character they call a libertine and it is not because they fear being seen to be encouraging libertinism. It is not an excess of political correctness that silences them. Rather, it is because they fear that sex is a dangerous force that must be repressed or avoided altogether. Eccentricity is discouraged, flirtation punished as lechery and sexual harassment. Casanova had found that as he got older the criticism intensified as if old men were not allowed to seduce younger women occasionally. Did this mean a tragic decline into dotage? No. He did not have to be turned into a symbol overloaded with unnatural meanings. If he was a grumpy old man, then that was merely the normal price of old age. His life did not peter out into sterility and despair. Seduction at his age had been a heroic enterprise!

All that is solid melts into air...