Vampires in Venice

George Sand vs Alfred de Musset

George Sand vs Alfred de Musset

Once upon a time, a famous woman novelist named George Sand liked to wear men’s clothes, smoke cigarettes and pipes and generally act out like “George.” With her black hair and olive skin, her imperial hooked nose and a wardrobe of ostentatiously exotic clothes, she reveled in her unfeminine independence. Needless to say, the bourgeoisie of mid-19th century France were scandalized.

These days Sand is better known among intellectuals - if she is known at all - as the lover and mother of the poet Alfred de Musset and the composer Frédéric Chopin, for few have read her books, and her love affairs have been made into several films, including Impromptu (1990), The Children of the Century (1999) and Chopin: Desire for Love (2004). She was a friend of the novelists Balzac, Dumas père et fils, Flaubert, Zola, as well as Franz Liszt, and she enjoyed a double life in cosmopolitan Paris and rural Berry and she was proud of both. She assumed the domestic and professional rights that were traditionally considered men’s and she got away with it. Worse still, she wrote about it and it sold.

Sand is sometimes thought of as androgynous yet she was more of a cross-dresser. Androgyny implies both masculine and feminine and falls somewhere in between, generating identity confusion and sexual ambiguity. Sand, on the other hand, actively adopted a masculine image, which does not mean that she was unfeminine. She was both rather than neither, depending on what role she wanted to play. She would wear extravagantly exotic costumes from a bad opera on one day and a severe black suit the next, in a century when men all looked like bankers and women were all tightly wrapped in corsets and crinolines. She crossed freely between masculine and feminine and found that this fascinated many men, especially the artistic ones who better fitted the androgynous label than she ever did. They were drawn to her theatrical imagination and her sense of satire. A gay prototype certainly.

The image of Sand and her associates that sticks the best, however, is the literary and sexual vampire. The vampire, after all, is a predator who seeks blood and uses sexuality to get it and he/she is generally indestructible unless you drive a stake through their heart. Vampires, like consumptives, tend to look like death warmed up, masked only by their exquisite fashion sense and a terrific sense of performance. Sand, of course, looked healthy and these characteristics can be better ascribed to her lovers. For the vampire look and its accompanying behavior was all the rage among the libertines and courtesans of Paris, the hunters of the night, as well as the consumptives who looked like they needed a blood transfusion, and among the bohemians of the Left Bank.

The vampire metaphor was already in popular currency during the 19th century to describe this community. Lord Byron taught other intellectuals how to recognize a vampire in the poem Giaor: “the freshness of the face, and the wetness of the lip with blood, are the never-failing signs of a Vampire.” Some thought this label better suited Byron himself: Lady Caroline Lamb accused him of being a libertine who preyed on women like a vampire. And John Polidori, an Italian who adapted the novel Vampyre from a Byron story about a libertine who pursues, seduces, marries and then kills a young woman, would have agreed with her. Similarly, the Polish poet, Adam Mickiewicz, wrote of Chopin and Sand that “Chopin is her evil genius, her moral vampire, her cross; he tortures her and will probably end by killing her.” He underestimated Sand’s strength but this sheds an interesting light on the portrait we have of Sand as Great Mother and Chopin as the tragic victim, a portrait spread initially by Liszt. For these are the essential characteristics of Romanticism, wherein all artists are vampires. What better image is there of the alienated, upper class, black-suited European intellectual?

Camille Paglia is one of the few academics to examine idea this in literature, but she attributes the phenomenon to the sexual energies of the Great Mother principle. Yet vampirism is neither feminine nor masculine or even purely literary and it is better identified with frustrated intellectualism. That is surely one of the themes Mary Shelley was exploring in Frankenstein, Or the Modern Prometheus (1818) and what drives the best short stories of Edgar Allan Poe in Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1840). Even in the early 21st century, the vampire persists in the behavior of lawyers, insurance companies, the media, the social welfare and education systems and the academics and foundations that support them as they feed upon others, especially those least able to fend them off. The vampire is a contemporary metaphor for those who have the power to write about and speak for others but who frequently feel contempt for their victims.

Back in the 19th century, things got very predatory and emasculating. The question is, Who was the sexual vampire here: George Sand or her lovers or both?

THE FIASCO

It was in the spring of 1833 that George Sand first took an interest in seducing prominent intellectual-about town, Prosper Mérimée. After he signaled his interest in return, they walked along the Seine before retiring to her home. Once there, however, she became restrained, even cool. This surprised him. In retrospect he did not read the signs right. She must have been secretly intent even then on humiliating him. The spider had lured the fly into her web; now she only had to sting it.

Sand had dressed for the occasion. Her hair was tied back in a hairnet and she wore a man’s shirt, a black cravat, and a yellow silk dressing gown that concealed everything except two bright red Oriental slippers. Mérimée quickly realized that she was imitating one of his characters, Madame Gazul, but whether to impress him or mock him, who’s to say? His original work had been a literary hoax after all. But when she placed a red muslin screen in front of a lamp, she managed to turn the room into Dante’s Inferno, not romantic Spain, and when the time came for it, she and her maid prepared the bed, she got undressed and he was expected to follow. If a woman undresses in front of you without romantic overtures, would you find it erotic? Mérimée resigned himself to undressing and joined her in bed where events were anticlimactic. She insisted on being on top and was physically aggressive without any tender expressions of love, and then he heard her immortal words: “I'm not sure about you.” They plunged on to no result. After a while, she bit him on the shoulder, which perhaps was meant to get him excited, or perhaps it was supposed to enrage him? They parted on bad terms.

Perhaps she had some abstract idea in her head that Mérimée was a romantic Don Juan who needed be taken down a peg or two? On discovering that this was not so, had she become confused? For his part, while he did have a taste for the Gothic and a sense of irony, she was too weird by far. He vowed to have nothing more to do with her, noting that she was “a woman whose debauchery was coldly deliberate -- the result of curiosity rather than temperament.” She retaliated by making sure all of Paris knew about their failed one night stand. Mérimée’s famous friend, M. Stendhal, called it le Fiasco, which indeed it was. A more literary version appeared in the counter-attack, M. Parturier’s Une Expérience de Lélia, où, Le Fiasco du Comte Gazul.

Round Two begins three months later when the celebrated young poet-lover and man-about-town Alfred de Musset meets George Sand. Again she is posing as Madame Gazul, a bright flower in her ear and a little dagger dangling from her belt. He asks her what the dagger is for and she says, “I often travel. Sometimes I dress like a man, but when I don’t, I need protection.” This was a provocative response and he liked it, so they traded sexual innuendoes for a while until he noticed that the dagger had disappeared into her jacket, perhaps indicating sexual surrender? He was 23, she was 29.

For a time, they exchanged the usual amorous letters and a little poetry – seduction by literature – and both were struck by the autobiographical resemblances they found in each other's work. Then de Musset decided to pay Sand a visit at her apartment. He found her dressed in a colorful silk dressing gown and the infamous red Oriental slippers. She offered him tobacco and sat herself on a cushion, puffing on a long-stemmed pipe. They did not get very far since they were interrupted by visitors, but he could see that she liked to mix the pantomime with self-mockery and just a trace of the truly bizarre. That is what he liked about her. They became tightly wound around each other, though at first she held back for fear of another Mérimée fiasco. He was in love with her by then. Thankfully she began to relax, and their first official night together was, necessarily, a totally rapturous experience. He moved into her apartment and they assumed the role of romantic rebels. They were young and crazy.

Let us get on then to the little melodrama that unfolded in Venice where they went on holiday together. They reached Venice in January of 1834, after taking turns in who felt worse. Italy was their image of abandon, of carnival, of Casanova, and they wanted to make full use of it in their next books, for literature will always be inauthentic unless one has actually experienced it for oneself. Imagine if you will, George wearing a red scarf wrapped around her head as a turban, a flowing tie sprawled across a white collar, and she is smoking cigars. This ensemble graces the balcony of their hotel, the Danieli, which she has refused to step foot outside of, claiming she isn't well. De Musset meanwhile contemplates retracing the steps of Byron through Venice in its spectral winter hues, as any other Romantic would do. His first few days are wondrous but he grows impatient with George’s illness and her lack of enthusiasm. She sulks, he grows angry. Neither has any money. Sand continues to stay inside and meets all suggestions with fresh obstacles. As she begins to recover, he wants her to accompany him but she says she wants to work. But she has writer’s block, which is unusual for her. After three weeks of her moping and complaining, he ups the stakes by saying “George, it’s all been a big mistake. Forgive me, but I don’t love you.” This is the ultimate gambit of course, so she locks the door between them and announces she wants to leave Venice immediately. A doctor – one Dr. Pietro Pagello -- is called for to take care of her. He consigns her back to bed.

Then the tables are turned. Alas, de Musset catches what Casanova caught many times and he feels absolutely terrible. They both realize that this is what people do in Venice in winter – they get sick – and they drop the pretense of enjoying themselves and settle in. Sand begins to enjoy the moods and rhythms of this truly magical city and especially the company of the charming Dr. Pagello. Of course, de Musset notices. Sand writes, “The frustrated roué, whose dreams of being a French Lord Byron had been reduced to a few nights of Casanovan dissipation, was now the cuckolded poet-lover and it was (I) who was playing the role of Lord Byron.” De Musset throws a fit with great dramatic flourish: “I only know how to suffer. There are days when I could kill myself; but I cry, or I burst into laughter... Farewell, George, I love you like a child.” Sand appreciates this theatrical and pompous performance. Thinking quickly, she decides she can rescue the poor boy from his darker side by indulging him. He spots this for the clever outflanking movement that it is and he is resentful. He proclaims that their love has taken on a bizarre incestuous quality. He decides she is becoming not just his mothering angel but also his destroyer! Sand retaliates by telling him to return to Paris, while she stays on to enjoy Venice. With finances running low again, they move to a cheaper hotel where he gets even sicker. Byron had also been sick in Venice but at least he had had a beautiful woman to nurse him back to health. All de Musset had was George driving him crazy by playing his mother instead of his lover. Before long George has invited Dr. Pagello to heal her poor boy as well. This is fortunate timing because de Musset now has a violent fit that lasts for days. He shouts, he screams, he goes into convulsions – it is quite a show – and he runs up some sizable medical bills.

De Musset had only slowly noticed that the intimacy between George and the athletic Dr. Pagello was deepening. He was sure he had heard them planning to go off together after ditching him. He thought he saw them sharing a cup of tea and even kissing, but he was still hallucinating and could not be sure. In a fury de Musset declares Sand an “infamous slut”! There was nothing else for it but to return to Paris and write about it. Back home herself, Sand and Pagello split up (he has tagged along) and she takes up again with de Musset. The affair sputters on for another year before he is finally free of her grip and able to transpose it into his grandiose memoir La Confession d'un enfant du siècle (1836). For some reason, Sand decides to sit on her own memoir.

NYMPHOMANIA AND FRIGIDITY

George Sand professed to believe in free love while claiming to be disgusted with promiscuity! But how can you have it both ways? She believed in being faithful to one man while she was involved with him, but she would ditch him when she lost interest. Franz Liszt’s secretary, Janka Wohl, captured this well in her later memoir: “Madame Sand took pleasure in capturing the butterfly with a sticky brush and in gaining its trust while she locked it into a box with aromatic herbs and flowers – this was the love period. Then she stuck a needle into it and let it writhe in a death agony – this was the dismissal, which always came from her. After which she dissected her ‘object’ and stuffed it for her collection of heroes for novels.”

The first of her weak and effeminate lovers was the 19-year old Jules Sandeau from whence she took the name Sand, and like the ones that were to follow -- de Musset, Chopin in his sicklier times, Alexandre Manceau to name a few -- she simply overpowered him sexually. She chose these boy-men because they were young, effeminate, consumptive, the idle class of aristocratic intellectual, easy prey.

This behavior disgusted Anthony West, who was the “illegitimate” son of H.G. Wells and Rebecca West and himself a novelist. The reasons for these Fiascos, he argued, could be found in George Sand’s upbringing. Like most deprived children, Madame Sand carried her neuroses into her adult life and attacked her men as financially or sexually inadequate. They in turn accused her of being frigid or insatiable or the financial equivalent... Was West referring to his own mother? Certainly Sand teased the public by implying she was frigid – she made her first popular character, Lélia, frigid. Even André Maurois calls his Sand biography Lélia because he says her book reads like a sexual manifesto of frigidity! Lélia agrees to sexual relations with her lover in this way: “Very well, I am disposed. Let it be as you wish, since it gives you such pleasure. But for my part I must tell you that it will give me none whatsoever.” She is lying of course. Like Sand, her frigidity was all part of the game-playing. It was a pretense masking the fact that, quite possibly, she was really the opposite, a frustrated nymphomaniac!

However, West, like the poet Mickiewicz, understood that these tactics were about more than just inflicting pain on a partner or spouse. Sand was also a masochist with a great capacity for suffering and in this too she could never be satisfied. Sadism and masochism in combination can be deadly for one partner or the other or both. When she tangled with Mérimée and he ignored her warning and made a public pursuit of her, they both ended up humiliated. Pagello did not conform to the feminine form she desired and so she cast him in a father figure role, which could not last, since she spent much of her life rejecting paternalism. George Sand enjoyed the sadomasochistic rituals of the effeminate vampire class far too much for that to endure.

NOT OUR LADY OF THE CAMELLIAS

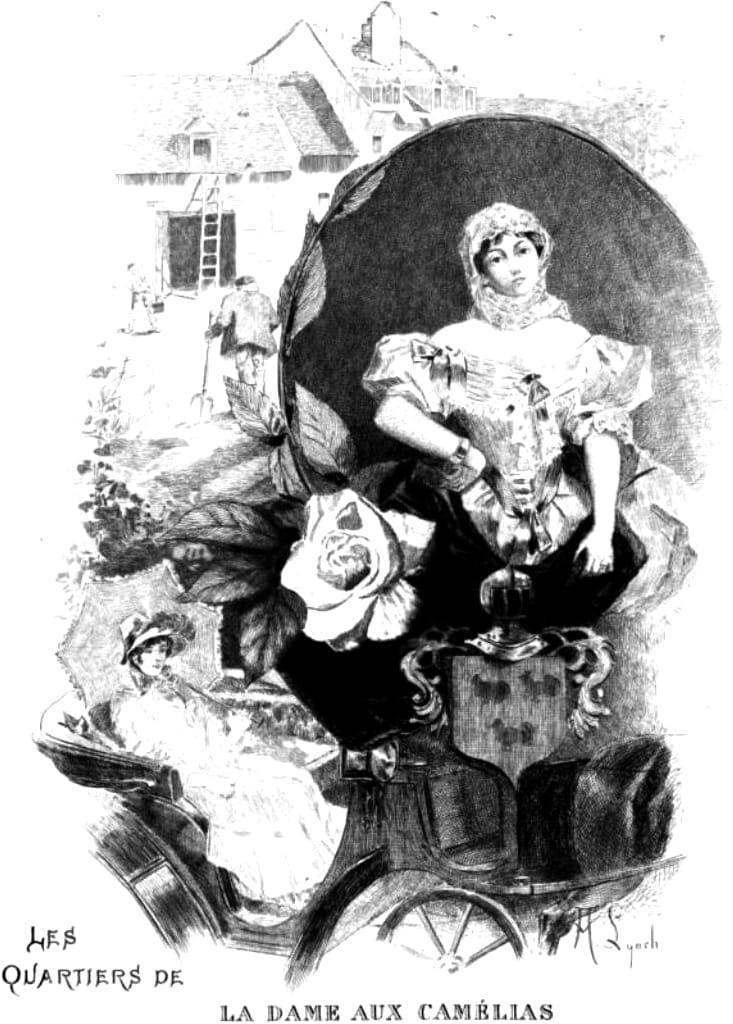

A lot of water has passed under the bridge. In 1852 Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin (George Sand to you) is out in the garden tending her red and white camellias. Her relationship with Chopin is in the past, having lasted from 1838 until 1846 (Chopin died in 1849). Over those years they had written many letters to each other and a package of her letters has fallen into the wrong hands. Imagine the literary consequences should they fall into the hands of an enemy!

Fortunately, her friend Alexandre Dumas fils, has managed to acquire them and, since he is overdue for a visit, he mails them to her instead. M. Dumas is more discreet than his father. He too is already a celebrity, for his novel La Dame aux camélias is the talk of Paris. It is indeed a moving story and it reminds Sand of Chopin and his losing battle against consumption. Marie Duplessis was only 23 when she died of consumption, two years before Chopin. Dumas’ novel also reminds her of Alfred de Musset. So feminine, so petulant, so much the adorable poet-dandy. She had liked “his floating blond hair, his vermilion lips, and his weary, nonchalant manner (which) were extravagantly admired.” On the surface he was a ladykiller who would sleep with any woman if she was available, which says something for his generosity of spirit, but underneath he was a lost soul. Highly-strung, schizophrenic and sadomasochistic, he was usually drunk. Why did Sand put up with him for so long? Because he was as exciting as he was insufferable. She recalled their first trip together, in August of 1833 to Fontainebleau forest, when he experienced one of his periodic schizophrenic fits, hallucinating that another man was staggering past him. Thereupon he discovered voila! – it was himself, his double, his doppelganger. Is schizophrenia endemic to frustrated literary minds? Fortunately, de Musset was fine the next day and they spent a pleasant week hiking through the forest. De Musset never wrote about it but Sand never forgot it either.

Sand grew up at a time when the Revolution had swept away all the cobwebs of the ancien regime. She once wrote: “All those lovely ladies and fine gentlemen who were so adept at walking upon carpets and bowing or curtseying couldn’t take three steps on God’s good earth without collapsing of fatigue... I think of my mother, who with hands and feet far daintier than theirs, did two or three leagues each morning in the country before breakfast, and lifted big stones and pushed the wheelbarrow as easily as she handled a needle or a piece of chalk.” Many of Sand’s lovers did not have the physical stamina and were, as often as not, disgusted by their own bodies. In Sand’s eyes, the modern woman would have no such weaknesses. If France was still hopelessly conservative for example, divorce had been illegal since 1826 – the freedom to write as one chose and make a living from it – as a woman or a man – was still a lot more important than one’s abstract rights as a woman. Sand remained skeptical about just how far women could push for reform in public life and instead she maintained an independence in her life that few other women seemed interested in emulating, but which was a lot more effective in making it possible.

VAMPIRES

In 1858 Sand finally publishes her amusing but scabrous hatchet job on poor Alfred de Musset, titled Elle et Lui. The man is barely a year in the ground and she portrays him as a mediocrity while her character plays the romantic heroine. Is there no respect for the dead? A second book, Lui et Elle, springs to his defense, but it turns out to be by Musset’s brother, Paul, furious at the attack on his family. Paul simply reverses all the nastiness and it is an inferior work. The hero is absolutely wonderful of course and the heroine intolerable. A third book appears -- Lui by Louise Colet, a friend of Musset’s (“Him”) -- and it too is a bit of a bore. Did Sand deserve the blame for starting this tasteless exchange, or could none of them help themselves really? After all, these events had happened 24 years ago.

If Wohl expresses the view that Sand was a particularly dangerous literary vivisectionist (others favor the Sphinx), the image that sticks with George Sand, her lovers and their coteries is as vampires. 19th century Paris was the perfect city for them. In its way Paris differed little from London or Berlin or St. Petersburg or New York -- the dark streets, the gaslight, the Noctambules lurking in the shadows. But, during this period, only in Paris were the dark thoughts transformed into a truly vast correspondence of letters, diaries and articles about their personal lives and everybody else’s. When the obvious similarities between their fiction and their erotic exploits were pointed out, they accused others of making things up. When Delacroix stated that Madame Sand drew on her painful separation from Chopin for her book Lucrezia Floriani (published in 1846), she denied it, because Chopin was still alive, but no one believed her. Was the prime reason for Sand’s Venice and Majorca trips literary sex? Not the customary intimacies and formalities indulged in by most of us, but transcendent sex where they imagine they are somebody else – Don Juan, Casanova, Byron – and they imagine they can live forever, breaking the barriers of space and time with their eternal beloved. Just as we may write literature or compose music to reflect our sexual lives, so we can arrange for our lives to imitate literature and music.

Every writer is really a vampire, as is every musician, every artist. The vampire feeds voraciously off the lives of those he encounters but we have to distinguish between two types. For every tragic and possessed and doomed vampire like Chopin and de Musset, there is also the flashy black-caped, performing vampire, like Liszt, or like Sand, for whom power was important, who preferred to live off and through the lives of others.

Liszt himself was born in Hungary and no doubt he dreamed of vampires in his early years as he was dragged across Europe on the concert circuit year after year. Though successful, he was never accepted into Parisian society the way Chopin was. It must have occurred to Liszt that fixing upon someone else’s music and “rearranging” it (as he did) was a form of vampirism, even if he felt he left the music healthy and alive after he had finished with it. A blood transfusion perhaps? His first introduction to the vampire may have been in reading Goethe’s Faust, for what was Faust but one of the earliest vampires? Many celebrated composers of the time tried their hand at interpreting the Faust legend: Wagner in 1840, Schumann from 1844 until 1853, Berlioz in 1846, Liszt in 1854 and again in 1861, Gounod in 1859. It would take until 1897 before Bram Stoker’s Dracula distilled the concept into the classic literary form we know it today and Freudian psychoanalysis would arise to explain it. In the 20th century Thomas Mann would be drawn to the demonic link between music and the legend in Doktor Faustus in 1947.

Romantic art and literature are only enjoyable if you get in the spirit of it. Consider the menu: incest, illegitimacy, homosexuality, effeminacy, doubles and doppelgangers, schizophrenia, angels and devils and the vampire. But whatever you choose, there is always a cost, a Faustian bargain. There are winners and losers. George Sand wrote of Chopin, “Pole that he was, he lived in the nightmare world of legend. The phantoms called to him, entwined themselves about him...” Especially after you’re dead. Liszt made sure everyone knew the phantoms had got to Chopin and that his creativity had dried up. De Musset prowled the nightclubs of Paris for years in search of his evil double but he was all washed up by the age of 25. His later work is empty, there is less irony and distance as he drifted into impotence and cynicism. Sand’s eyes haunted him for years, they say. Sand herself did not escape unscathed. There were the accusations that she was a schizophrenic or a lesbian, even if the rumors were just typical Parisian salon gossip. No one emerges unscathed. That was partly the point.