Water spirits in European art

Mermaids, fairies, nymphs, sprites, sirens, kelpies, selkies and xanas are children's entertainment nowadays, right down to the new phenomenon of "mermaiding." This wasn't always the case. In 1917, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was fooled by the Cottingley Fairies, photos taken by two young girls (Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths) like the one below. Paranormal hoaxes continue to this day, but with fewer mermaids and fairies.

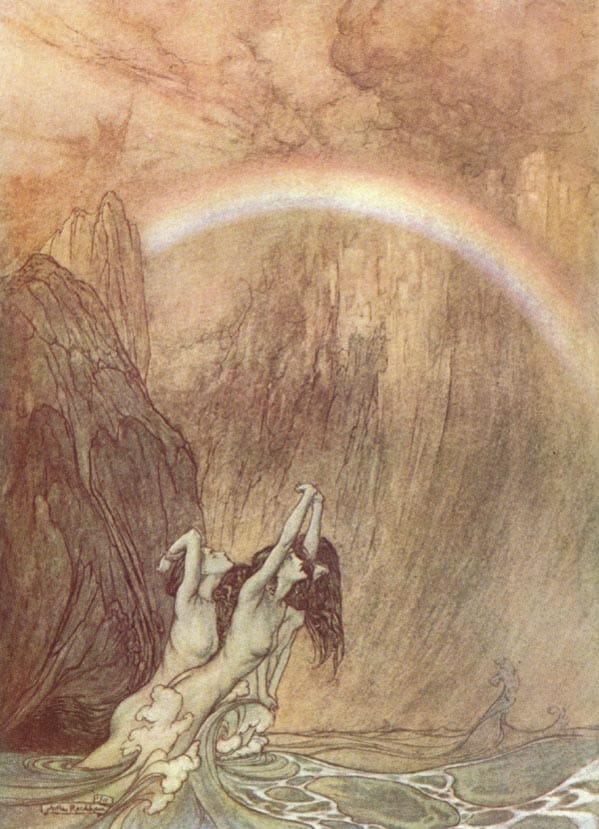

Historically, the most attention water spirits get is the Greek nymphs, naiads and Sirens. In the Odyssey, Calypso was a water spirit and Circe was the daughter of one (an Oceanid nymph). Then there was Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Mermaid. But, there are many others that are neglected. They include the Slavic rusalki and vile (or veela in Harry Potter), popular across much of Eastern Europe, the mavki (Ukrainian), and the Scandinavian/Germanic nixie and hulder, notably Wagner's Rhinemaidens and the Lorelei.

Perhaps they are just the children of nature everywhere, like in this Polish masterpiece The Goddess in the Mullein, one of my favorite paintings. The medicinal plant mullein is associated with Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft, magic, and crossroads.

Despite the neglect in pop culture, there is an enormous literature on the subject of water spirits and back in 2018 Wikipedia struggled to sort out all the distinctions. For example, what do you make of the mermaid sculptures all across Europe like the one below, or their popularity among contemporary young digital artists. Some good questions might be: why are water spirits so widespread across cultures; why did earlier peoples imagine them as human-like; and why were so many female and nude?

The standard answer seems to be that earlier civilizations believed in Animism, whereby everything in the natural world, including plants, animals, rivers, lakes, rain, wind has a soul or spirit, and we humans (who are also a part of it) can relate to them better if they take human form, especially a nude female form, signifying fertility. If that's true, humans have mostly lost this connection as we rush headlong to destroy the natural world.

Water spirits are on every continent, including Asia (the nāgas, ningyo), Africa (Mami Wata), the Americas (Iara) and Polynesia (the taniwha). Some are shapeshifters. Some have tails, not legs. Some are girls who died a premature death. Some lured men to their deaths (like the mavki); others are beneficial. The variety is endless.

Some of the most interesting water spirits come from Slavic folklore, like the rusalka. She is found near water and in fields, forests, and mountains. Rusalki were linked to fertility and nurturing crops and only by the 19th century were they considered dangerous or evil or even walking dead. For example, some may have been young women, who died by suicide (usually drowning) due to an unhappy marriage or who were violently murdered. I particularly like this vila sculpture from the southern part of the Czech Republic:

The Kalevala is Finland's national epic, compiled by Elias Lönrot and first published in 1835. In it, Aino escapes a forced marriage to the main character, the sage Väinämöinen, by transforming herself into a water spirit called a nixie (or she drowns, depending on your interpretation).

And then there's Harry Potter. This below is the Great Lake at Hogwarts, inhabited by Merpeople, Grindylows, Sprites and a Giant Squid (c.f. the Zora people of Nintendo's The Legend of Zelda.)

Also see Melusine, Lorelei, The Little Mermaid, Ophelia, John William Waterhouse's Sirens.