The Woman in the Bower

A Murder at Woodstock: Fair Rosamond vs Eleanor of Aquitaine

A Murder at Woodstock: Fair Rosamond vs Eleanor of Aquitaine

Once upon a time, a young maid named Fair Rosamond was murdered by jealous Queen Eleanor in the royal palace of Woodstock, near Oxford. Despite the best efforts of King Henry II to keep his women apart, evidently he had failed. The question that remains: who was the villain of the piece?

Was it Rosamond Clifford the mistress, or the unfaithful King Henry of England or his vengeful wife Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine? Over the centuries there have been many tales of jealous lovers killing the object of their affections and today’s television news and tabloids thrill to exposés of husbands killing their wives, wives killing their husbands, mistresses hiring contract killers to shoot their male friend’s wife, and so on. Crimes of passion are always difficult to explain, which is of course why they are so interesting. But how was it done back in the 12th century?

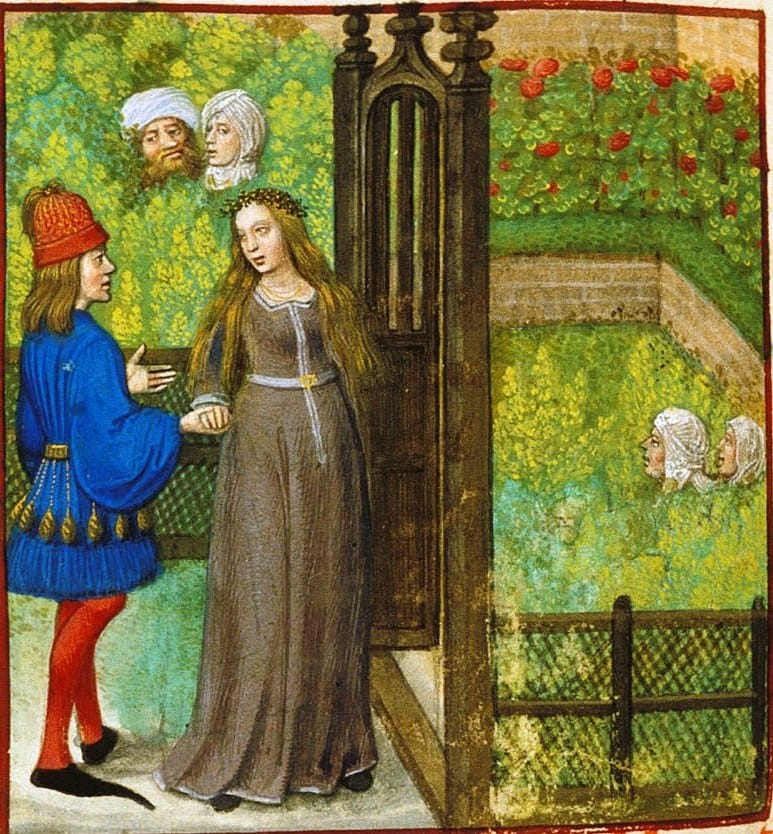

It was widely known at the time, throughout both England and France, that Henry was having an affair with young Rosamond de Clifford. Eleanor’s spies reported the goings-on to her in her castle at Poitiers, to which she had now retired. It seems that as the affair persisted, she became angrier, since Henry’s past affairs had never lasted long and this new infatuation appeared to be growing more intense. Eleanor decided to act, stealing into England with her knights, headed for Woodstock, where Henry had his mistress hidden away. The palace was deep in the forest and its approaches were constructed like a labyrinth designed to foil Eleanor, should she ever decide to do what she was doing now. Alas for Rosamond, a silk thread had become detached from a needlework chest that the King had given her for embroidery. Once the Queen discovered it, she was able to follow it to the heart of the labyrinth and surprise the young woman. The Queen’s soldiers quickly overpowered the single brave knight who was there to protect her and at last Eleanor confronted her nemesis. She offered Rosamond a choice between a dagger and a cup of poisoned wine. Rosamond apparently chose the poison and died, and that was the end of her, or so the story goes.

FAIR ROSAMOND’S STORY

King Henry had first taken a liking to Rosamond, the daughter of one of his knights, nine years earlier. Her father, Walter de Clifford, had a castle on the Welsh border and Henry probably met her there during one of his occasional wars of pacification of the Welsh, who quite unreasonably wanted to remain free.

Fair Rosamond of course was very beautiful, an English rose, though her name means “Rose of the World” in Latin. Henry was drawn to her softer form of femininity, so different from his wife’s, for Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine was the kind of woman who made men behave respectfully whenever she was around. An “overbearing, vindictive woman,” wrote Jane Austen biographer Elizabeth Jenkins in 1955, taking sides with Rosamond in her book Ten Exciting Women, depicting Eleanor as the kind of woman that strong men like Henry run away from. Katherine Hepburn was the perfect choice to play her in the Freudian-inspired film The Lion in Winter (1968) about their later years together, as was Glenn Close in the 2004 remake.

In Rosamond’s town of Bredelais, the peasants and ordinary working people had ways of courting so that couples had a chance of finding out whether they could get along together. Things seemed to work a little differently among royals. Rosamond knew Henry was a womanizer long before his arrival. Indeed it was common knowledge that he had mistresses all over the kingdom. This pained her father deeply for he saw the way the King looked at his daughter and he knew where it would lead. He knew other fathers had kept their daughters out of the King’s sight; should he have done the same? Yet it appears the King genuinely did fall in love with Rosamond and she too could find it in her heart to love him, though she was frightened she was sinning against God. The predicament aroused intense emotions in her – he was the King, after all. She tried not to commit adultery in her heart because adultery was a mortal sin, but women are the weaker sex, just as prone to sin as the men, if not more so. She also knew she did not have to look further than the Queen to see who was encouraging the immoral behavior that was all around her, for everyone knew the Queen had her own affairs.

Rosamond could not see how love and marriage could be compatible. The royal marriage, for example, seemed little more than a business arrangement. Henry and Eleanor clearly had married each other to produce a male heir and make their kingdom bigger. It had nothing to do with love. True, the King and Queen were both good administrators, he was a good soldier and she was very cultured in her own way. Perhaps they had liked and respected each other at first? Married now for many years, they had eight children to show for it. But people grow apart and a long marriage does not satisfy our sexual or spiritual natures. Once the Queen had produced male heirs, they both considered themselves free to pursue their own affairs, and Rosamond assumed this was what Eleanor was doing now that she had moved back to Poitiers.

Between 1165 and 1174, with Eleanor out of the way, Rosamond traveled with Henry whenever she could, but at a certain point the affair became public knowledge and it turned nasty when Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis) wrote a scathing public attack on Rosamond:

[Rex] qui adulter antea fuerat occultus effectus postea manifestus non mundi quidem rosa juxta falsam et frivolatissimam compositionem sed inmundi verius rosa vocata palam et impudenter abutendo.

His real target was Henry, because of the King’s frequent wars against Wales, but the main casualty was Rosamond. He mocked the King’s mistress as Rosa-immundi, “Rose of Unchastity” and everyone enjoyed the joke. For Rosamond, it was too much and she brought the affair to a close. She joined her sisters at Godstow Nunnery and she did not hear from the King again. Inside the walls, she was unaware of the rumors swirling around the country of her imminent murder.

Rosamond herself only ever wanted to be a nun. She prayed that one day a courageous woman would write a book that truly reflected what she believed, a book like Christine de Pizan’s City of Women. That book describes a women’s utopia where the Virgin Mary and other virgin martyrs are in charge, not the men, and where there is shelter for all good women. These women warriors will repel the spiritual assaults of the men just as women like her had had to repel their sexual assaults in the real world. There was strength in sisterhood, in virginity, in chastity. While she was unable to draw on them in this world, to resist the King, her comfort would come through prayer and the divine grace of God now that she was safely inside the Nunnery. She hoped and trusted she could attain salvation once again.

QUEEN ELEANOR’S STORY

Queen Eleanor was one of the most extraordinary women who ever lived, the subject of many biographies and, in her time, the talk of Europe on account of her two marriages: first to King Louis VII of France and second to his rival, King Henry II of England. But when she gave birth to her last child in 1166, it was a difficult child named John, who would distinguish himself by signing the Magna Carta.

Queen Eleanor was 45 years old and King Henry was 34. After 15 years of marriage, she had had enough. Initiating their separation, she moved back to Poitiers. It was not because she planned to indulge in more affairs, free from interference, though this had its appeal; it was because she still had a kingdom to run.

For the next nine years, Eleanor would hear occasionally about Rosamond. She had to accept that this was the first mistress Henry had taken seriously. Poor girl, obviously a virgin when he seduced her. Eleanor’s spies told her that Henry had arranged for a procuress to lead the young woman astray, exciting her sexually with drawings before he stormed the castle moat. But Eleanor never met Rosamond and what her husband did in his own time at this point was his affair, as far as she was concerned.

Rosamond was now living at Woodstock. Eleanor had stayed there frequently. It was really more of a comfortable hunting lodge than a palace. Henry had leopards and lions running around in the park to enhance its wildness. Even deeper in the forest, at Everswell, there was a bower and a garden that Henry had built originally for Eleanor, not long before they were separated, in one of his intermittent efforts at being romantic. Henry had landscaped the garden to tell the story of the doomed lovers, Tristan and Yseult. What was he trying to say with this? In the original story, when the lovers were separated, Tristan communicated with Yseult by placing twigs in a stream that ran through Yseult’s bower, which was in an orchard surrounded by a huge wall. Perhaps he was prescient about the future of their marriage, for soon they would barely be communicating themselves? At any rate, the story would become source material for the idea that Rosamond was hidden inside a bower inside a labyrinth inside a palace inside a forest.

Eleanor in truth had nothing to do with Rosamond’s death. Over the years, ridiculous stories emerged that seemed designed to blacken Eleanor’s reputation nonetheless. She wondered initially if Henry had put the English historians up to it, just as his ill-advised remarks inspired four reckless knights to assassinate Archbishop Thomas Becket at Canterbury. The stories were certainly wild. But Eleanor was contemptuous of such fables. What would have been the point of killing Rosamond anyway? She kept Henry occupied! If Eleanor had truly felt like revenge, she could have forced Henry to send Rosamond back to the nunnery. From what she heard, Rosamond would have preferred that anyway.

In Poitiers, Eleanor was able to pursue her own career again. England was such a wet and dreary place after all. The English were envious of life in southern France – its culture and civilization -- and she was its patron and symbol. She had learnt the way of the troubadours from her grandfather who was quite a bawdy poet of love in his own right. His poetry had been unsubtle, sexually crude, worldly. He did not express the ethereal or the spiritual art that flowered in the words of the great troubadours of her generation, but he did inspire Eleanor. Like her daughter by her first marriage, Marie the Countess of Champagne, Eleanor tried to introduce new ideas of chivalry and culture to her excessively masculine world, so that women might have more of a say in their lives. Romantic and sexual love had to find an outlet somewhere and this is why she encouraged the idea of the medieval Lady, as a contrast with the ever-present Virgin Mary or Mary Magdalene. Women should be able to wear cosmetics and enjoy fashion and independent thinking. If a woman wanted to have an affair, then that was her business. The men did it. Hopefully the customs of courtly love might disarm the men’s aggression. If a man had to listen to songs of love and romance, and if he had to catch the eye of an attractive woman, he was much less likely to rape his way to self-satisfaction and a male heir. He might even learn that women have rights too, he might learn to be discreet, and that the social order might be better protected from a profusion of bastards if the incidence of adultery could be reduced. It was not the fact that Henry wanted to spend more time with the virgin that annoyed Eleanor, but the fact that the English now were pinning the blame for Rosamond’s death on her.

Eleanor of Aquitaine was careful not to leave any records behind that might be misinterpreted – no letters, no papers, no poetry. The unintended consequence for her, however, was that for centuries in English literature it was Rosamond, Rosamond, Rosamond all the time. Eleanor herself attained the status of monster, demon, temptress and adulteress, and even murderess. Ironic, isn’t it? The husband has the affair and everybody blames the wife for it.

KING HENRY’S STORY

King Henry II of Anjou, the husband, was actually Norman French, but in the popular imagination of olde England he was all right. While Henry himself was no saint, and he would have been the first to recognize this, he did believe that the most sympathetic character in this whole sad affair was surely poor Rosamond. There are good reasons for why the story is known as “Fair Rosamond,” not “Fair Eleanor.” Eleanor (or Alienor in olde French) was a jealous “alien” witch and if she didn’t exactly poison Rosamond, then she poisoned her mind and everyone else’s.

By contrast, Henry liked to think of himself as a romantic man. The forest bower of Tristan and Yseult had been his idea. The bower was as beautiful as a fairy tale -- a very sensual place, full of fragrances and birdsong. But it was designed to keep Eleanor out and Rosamond in. He knew it and Eleanor knew it.

Henry had mourned Rosamond when she died in 1176 at Godstow Nunnery. It was said that she became a nun on her deathbed, but in a way she was always a nun, dwelling sadly on her misplaced sense of guilt. Her grave at Godstow would become a shrine for many young women who saw in her a romantic Magdalene figure. Things were marred only when a nasty old bigot, St. Hugh, bishop of Lincoln, showed up at her grave and ordered the remains of the “harlot” be removed to the cemetery like everybody else’s.

For Henry, the contrast between Rosamond and Eleanor was stark. Where Eleanor came from, there were no limits to their ambitions and passions and he knew Eleanor for the threat she was. Many years before Eleanor was born, her grandfather, Duke William IX of Aquitaine, fancied a viscountess with the curious name of Dangereuse. The fact that they were both married proved no problem for William. Just like in the legends, he kidnapped her from her husband’s castle of Chatellerault and carried her back to Poitiers, and Dangereuse approved of the idea! Nothing like an abduction for adding spice. William set her up in her own tower attached to his castle and the affair soon became public knowledge. His jealous wife tried to enlist support from the Church and other disgusted parties to get Dangereuse moved out, but she did not succeed and the wife left in a rage. Dangereuse already had three children by her previous marriage, and she was able, some years later, to marry off her oldest daughter to William’s oldest son, thus marrying her family into the dynasty. These two became the parents of Eleanor of Aquitaine. The moral of the story is an ironic one: William and Dangereuse had a romantic appeal to the young Eleanor when she was growing up. But now the roles were reversed: Eleanor was playing the role of the betrayed wife, not the beautiful mistress carried off in her lover’s arms and installed in his tower of love.

So why did the story develop all the garnishings? Because, as Henry feared, Eleanor eventually turned on Henry and conspired with her sons, her allies and their armies to seize the throne from Henry. The English have never forgiven her treachery; Eleanor was seen as a usurper. Just as she stole into the bower to murder Rosamond, metaphorically at least, she and her sons sought to destroy the kingdom. Eleanor was the serpent whose nasty bite poisoned everyone around her. In the end, Henry was obliged to have Eleanor locked up in the tower of Chinon castle in the Loire Valley for months. He then put her under house arrest in various castles around England for many years, which in a manner of speaking made for an interesting twist on our morality tale of the lady in the bower, for Eleanor got to live in Rosamond’s bower. Sometimes revenge is sweet.

THE SCENT OF ROSES CRUSHED

Charles Dickens thought he had the final word on Fair Rosamond. In his Child's History of England (1851-53) he writes: “There was a fair Rosamond, and she was (I dare say) the loveliest girl in all the world, and the king was certainly very fond of her, and the bad Queen Eleanor was certainly made jealous. But I am afraid -- I say afraid, because I like the story so much -- that there was no bower, no labyrinth, no silken clue, no dagger, no poison. I am afraid Fair Rosamond retired to a nunnery near Oxford, and died there, peaceably.” In other words, there is not a shred of evidence to support the idea that Eleanor was responsible for Rosamond’s death, whatever popular folklore has to say about it. Eleanor’s biographers agree.

But who cares? Fair Rosamond is a wonderful tale of feminine jealousy. In this story we have two women fighting to the death over a man. Imagine Eleanor storming into the sanctuary and there we see Rosamond weaving or spinning in her bower. She is singing while she works, like Rapunzel. Tradition would cast a man as the invader, for a bower is an open invitation for the hero to scale the walls and ravish the women inside, like William took Dangereuse. But here it is Eleanor, playing the male role, who storms the sanctuary and instead kills her rival.

This story always carried within it its own possibility of reversal. Could Rosamond find a way to poison or stab Eleanor? In medieval times many women lived in their own quarters, sewing and embroidering, out of the reach of men, and some had secret knowledge of poisons and potions. They could be considered dangerous to men if they decided upon revenge. While they could heal, they could also kill.

During the 16th and early 17th centuries, the poets and scholars mostly just blamed Eleanor, accusing her of immorality, for leading the beautiful young woman astray. A couple actually punish the Queen but most are content to weigh the relative evils of the two women and come out in Rosamond’s favor. Henry gets off scot-free. At this time, poets bored with the story became far more interested in the engineering of Rosamond’s labyrinth: was the entrance underground, how many doors and corridors were needed to create it, how much stone and timber? With the absence of passion, the architecture becomes more important than the murder.

During the 17th century, the chapbooks sold by itinerant traders traveling throughout the villages of England continued to show Rosamond as the virtuous beauty, slow to be seduced, but ultimately led astray by a false governess. Not Henry though. Never Henry. The theme of the fallen woman doesn’t go out of style.

Then at the end of the century, a shift appears. John Bancroft’s play of 1693 has Rosamond die in Henry’s arms and it is flippant about her. A few poets and playwrights went further and took Eleanor’s side against Rosamond. From a dramatic point of view this is a mistake since innocent victims make for more pathos, but this was the heyday of satire. In Joseph Addison’s mediocre opera of 1707, Eleanor considerately uses a sleeping potion, not poison, so that Rosamond can be dispatched to the nunnery without a fuss and Henry and Eleanor can be reconciled. It was a failure, needless to say. The theater-going public wants blood and excessive displays of passion or they won’t show up. It was also around this time that Woodstock disappeared. The Duke and Duchess of Marlborough tore it down in 1704 to build their new palace; apparently the Duchess was not a sentimentalist and Blenheim Palace now sits on the spot. For the rest of the 18th century, the story was neglected, though a few narrow-minded moralists used it to attack licentiousness.

In the 19th century, the story makes a comeback. The Romantics adored Rosamond, preferring to keep her alive if they could, as long as someone else got killed off. Barnet (1837) switches things around so that Rosamond’s father rescues her heroically in the nick of time before she drinks the fatal poison! This is emotionally unsatisfying: who wants Dad getting involved? Better to imagine Henry as the vile seducer and Rosamond as the beautiful heroine on her knees before Eleanor the witch queen, pleading for her life. Add the knives and the poison, then place the story inside a labyrinth recalling Ariadne and Theseus’ flight from the Minotaur. It is a tale rich in operatic possibilities.

Tennyson returned to the subject decades later with his play Becket (1884). In it he decides to have Henry marry Rosamond, then keeps her locked away in the bower so that she will never hear of his bigamous marriage to Eleanor. He then has Archbishop Thomas Becket steal into the labyrinth, save Rosamond from Eleanor (and Henry) in the nick of time and sweep her off to the nunnery. Becket is later killed in the cathedral and Rosamond is last seen praying over his dead body. Not a bad twist, but no future as an opera.

In the 20th century, the lesser-known English poet Michael Field portrayed Rosamond as a country girl who, when confronted by Eleanor, chooses the dagger over the poison. This just doesn’t ring true, but then “Field” turned out to be two women using a pseudonym. Putting the story to better use, the poet John Masefield has Dark Eleanor poison Fair Rosamond and ever after she is haunted in her dreams by the “scent of roses crushed.” This is a nice touch – to make her suffer from a guilty conscience. But even if the poets did their best to keep the spirit of the Romantics alive, the ruthless biographers and historians have since regained the upper hand and rehabilitation of Eleanor has prevailed. As her biographer, Alison Weir, puts it, she “was one of the great heroines of the Middle Ages” – and Rosamond is banished to obscurity once more.

THE PRINCESS OF CLEVES & THE PROPHET MOHAMMED: is honesty always the best policy?

In this day and age, when people learn their spouse has been cheating on them, they behave much the same way Eleanor did. They want to murder them, or the lover, or both, or at the very least toss them out of the house. Murder can be messy. Eleanor found out about Rosamond and she may have vowed to kill her, but not because of the affair itself, for Henry had had affairs before, as had she. Rather, she felt this way because his relationship with Rosamond seemed to be turning into something more than a mere fling. Isn’t that what most married people fear the most – when a casual affair metamorphoses into the real thing?

Would Eleanor have benefited from a frank conversation with Henry? Would Henry have benefited from a frank conversation with Eleanor? Yet is honesty ever the best policy? Perhaps there are tactical advantages to confessing one’s love for somebody else before the spouse ever finds out about it. Perhaps a confession can save a marriage. However, history seems to say otherwise, if the objective is to keep the squabbling married couple together. Dishonesty may be a better policy in that sometimes a spouse doesn’t want to know. Even if they do know, it may be better for their state of mind if they never find it confirmed.

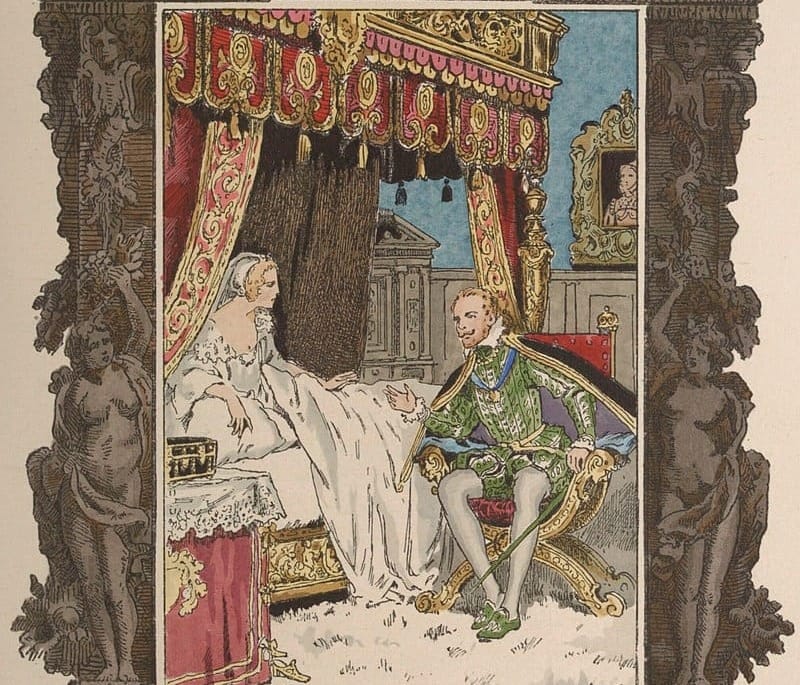

In the 1678 novel La Princesse de Clèves, a confession produces an unfortunate result. In this novel, which was written by the Comtesse de la Fayette, a contemporary of Ninon de Lenclos, the Princess confesses to her husband that she is in love with the Duc de Nemours. She does so because she respects her husband enormously and the marriage is by all standards a highly successful one. She has resisted the temptation to stray till now out of loyalty to her husband and to her oaths. But she also wants to make sense of her powerful feelings. Unfortunately, Nemours is outside the window and he hears her confession. He doesn’t keep the news private and the married couple is devastated by the gossip. Very much in love with his wife, the husband is so upset by the false rumors of his wife’s infidelity that he dies of unhappiness.

Now the way is free and clear for the Princess to pursue the relationship with Nemours. But she chooses not to and instead favors abstinence for the rest of her life. Her reasons are interesting. For one thing she feels somewhat guilty that her husband died for love of her and thus there is the matter of integrity. For another, she doesn’t want to sully the powerful memories of her love affair with Nemours by watching them fade and tarnish as all such infatuations inevitably do. But in this case, if her honesty is not the best policy, then it certainly resolves the situation. It hurts everyone involved but at least she emerges feeling she is vindicated to some extent. One wishes her husband had displayed a little more fortitude and that the Duc de Nemours had been more discreet, but that is not what happens in reality. Is it?

In early 2006, a Danish newspaper published cartoons of the prophet Mohammed and stirred up a worldwide controversy over what is acceptable to say, or display, in public. The controversy has been going on forever, especially in France - Charlie Hebdo, etc. - and even some teachers have lost their lives over it. But, it cuts both ways, not least the banning of the abaya and qamis in schools and burkinis in public pools.

The moderate Muslim world in this fable resembles the Princess of Clèves: many Muslims are attracted to the energy and openness of the West (the Duc de Nemours), but are reluctant to flirt too openly for fear of upsetting the Islamists (her husband). Unfortunately, certain elements in the West (like the Duc) are fed up with the Islamists (the husband) and they publicly flay Islam and the prophet Mohammed and prescribe a lot more democracy for the Muslim world (i.e. let us have an affair openly). The result? Traditional Islamists are enraged and many die in fierce protests across the globe (the husband dies). Moderate Muslims are put on the defensive and forced to renounce their interest in democracy (as the Princess does). The West pronounces shock at the explosion of rage (the Duc is shocked…shocked). It is a parable for Gaza...

Are we all better off for this anger, cynicism and appalling behavior? Again, the best solution might have been discretion, but that is not what happens in reality. Is it?