Voices and Saints

Was Joan of Arc a Virgin?

Was Joan of Arc a Virgin?

Once upon a time, virginity had true spiritual power. Not in today’s cynical world, perhaps, for it is difficult to persuade the modern Western reader that in medieval times, as in many cultures today, an extremely high value was (and is) placed on female virginity because of its associations with purity and beauty. This is why Saint Joan of Arc - "Jeanne d'Ay de Domrémy" - was known in French as la Pucelle, literally “the Maid,” the Maid of Orléans, meaning that she was a virgin.

Joan of Arc was not made France’s national saint, however, until 1920. Why did it take so long? For one thing, it could never be confirmed that Joan was indeed a virgin, and virginity was a prerequisite for sainthood, or even for that matter that she was a woman. For another, there was the vexed question of which “France” she represented. She came from the outrider provinces after all and France at the time looked like a great jigsaw puzzle.

Most 15th century reports agree that Joan was a good-looking young peasant girl, strong physically and with great endurance. But we also have reason to believe that a number of women in the late medieval period grew modest beards or dressed as men in order to escape from their families or from disastrous marriages. Some even entered monasteries – as men – or went on pilgrimages or, as in Joan’s case, became soldiers. It would be an easy slide to the assumption that perhaps she was a man. But we know from her contemporary, the Duke of Alençon, and others who testified, that they had seen her undressing. “Her breasts were beautiful,” he said, and why should we disbelieve him? At her trial in 1431, her judges deemed that an additional inspection was necessary and if she indeed had turned out to be a man in drag, her judges quickly would have concluded she was from the Devil and burnt “him” at the stake without a trial.

Beard or not, I think it is safe to assume Joan was a woman. Most of this controversy can be attributed to inquisitorial zeal – to finding reasons to justify burning her at the stake. The judges certainly came to the conclusion she was a woman, so they turned their attentions to the other key question of the age, Was she a virgin? This is her story.

THE ARCHANGEL SAINT MICHAEL

Many centuries earlier, back in the time of Merlin, there was a prophecy that foretold that France would be lost by a woman and saved by a virgin. As everyone knows, the foolish woman who lost France was the mother of the current Dauphin, Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, who had sided with Burgundy and the English, and who now had gained control of most of the north, including Paris. It would be the Maid of Orléans who would be the virgin who saved France at the age of 19, supported by another powerful woman, Yolande of Aragon. But we are jumping ahead.

When the Maid was 13, a young peasant girl growing up in the charming village of Domrémy in Lorraine, she was visited by the Archangel Saint Michael. France was wracked by civil war, villages were burning, crops destroyed, partisans executed. As the 19th century French historian Jules Michelet would say: “She realized the full meaning of war. She understood this anti-Christian condition; she was horror-stricken at this Devil’s misrule under which every man dies in a state of mortal sin.”

Something had to be done about it. The traditional patron saint of France, Saint-Denis, had proved to be a disappointment – too isolated in Paris perhaps – and Saint Michael had stepped into the breech. Was this the time foretold in the book of Revelation, thought Joan? As the new standard bearer of Christ’s armies, Saint Michael remained vigilant against the return of the Antichrist who could come at any moment. As that prophetic book says: “There was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, and prevailed not.” Saint Michael had been drawn in on the side of the French and, in his mind at least, Joan seemed nothing less than a virgin saint put on God’s earth to save France. But at first Saint Michael merely told her to be a good girl and to go to church regularly. He did not elaborate. Evidently he wanted only to impress upon her the power of the armies of heaven, by taking the form of the stained glass image in her local church, arraying behind him a host of angels in full battle dress. She was impressed, as any young person is when confronted by chaos all around them and the means to do something about it. This was when Joan first felt the calling of a warrior. She was ready to ride the four horsemen into history in the coming war for the liberation of France.

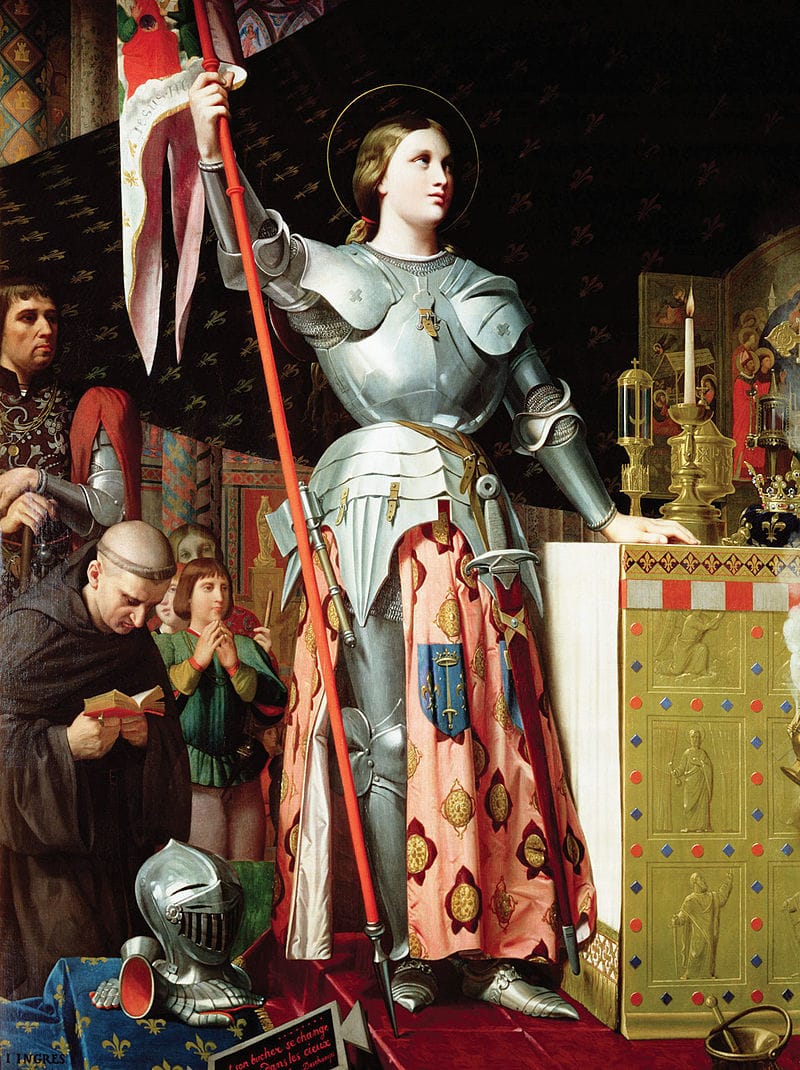

Joan of Arc’s initial objective in 1429 was to persuade other knights to accompany her to Chinon to meet the Dauphin and from there she hoped to lead a unified French army into battle at Orléans. Over the next year, she successfully carried this out, raising the siege of the town and routing the English armies at Patay (shown below). These were spectacular, seemingly divinely inspired victories, helped in no small way by the fanatical loyalty she engendered in her own troops (many of the regular soldiers were in fact mercenaries with dubious loyalties). Joan represented old-fashioned chivalric values grounded in religious faith combined with a dynamic will for taking the fight to the enemy instead of sitting around talking about when to retreat. The French armies were able to advance to Reims in the following year where the Dauphin was crowned King Charles VII of France. Her brief military career came to an end when she was captured shortly afterwards in May (of 1430) by the Burgundians, who sold her to the English six months later. The English kept her as a political prisoner and then put her on trial in Rouen.

We do not concern ourselves here with the conclusions the male trial judges came to; they were in the service of the English Crown and their French collaborators. Instead we turn to something much more important: the two medical inspections she had to undergo during her brief but illustrious career, for as I argued above, the critical issue was whether she was a virgin. If she was, this would confirm the famous prophecy and her purity before God; if she was not, then she was a fraud and the war for the liberation of France was a fraud. Everything else was just politics. The first inspection had occurred earlier at Poitiers by the King’s mother-in-law and the noble ladies of the French court and while they may have been predisposed to lie, all doubt was removed the second time. This inspection took place in Rouen, by the English noblewomen no less, and they had no reason to lie. They stated that the barricade was still in place. While Joan’s purity was certified by her enemies, it would not save her life, for she was too dangerous a symbol. After a year in prison, la Pucelle, the Maid of Orléans, died a martyr’s death, burned at the stake in 1431.

Yet events were set in motion that day in Rouen that would end the Devil’s rampage across France. To the Archangel Michael, Joan’s death was a necessary if painful blood sacrifice. At heart he was a military man, he followed God’s orders, and his orders were to see that she was burnt at the stake as a martyr so that France would be roused to anger. This would happen, as the repercussions of an invalid and rigged trial and the rage felt by many French men and women resulted in a massive dislocation of the English and Burgundian plans. Michael had an appreciation for the beauty and clarity of this moment. He knew that Joan had never actually killed anyone in battle, so he conjured up a miracle to capture it. As the Maid gave up her spirit to God, he arranged for a white dove, flying from the Ile de France to soar above the city of Rouen before disappearing into the blue skies of the West. In an alternative version, an English soldier by her in her last moments at the stake said that when she died, a white dove flew out of her breast and flew toward France. At any rate, within five years the English armies were on the run, to be driven out of France forever, and setting the stage for a unified France. The fulfillment of the prophecy is rousing stuff, particularly those visions in the sky. Saint Michael would go on to have his image emblazoned on all French standards and his shrine at Mont-St.-Michel, which the English failed to capture, would become one of the most impressive landmarks in Europe. Later in the century he would go to Spain to lead the fight against the Muslims based in Granada, before seeing service in the Americas, as San Miguel, angelic warrior of Catholic imperial Spain. Joan’s reputation, on the other hand, would not be vindicated for many centuries to come.

SAINT CATHERINE OF ALEXANDRIA

If it had been up to Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Joan would not have been raped in this way. Like Saint Michael, she had visited Joan out in her father’s fields one soft sunny day. Catherine had not wanted to frighten her so had taken the guise of a young peasant girl with orange hair, descending from a cloud. She hovered in a tree while her companion Saint Margaret alighted in another tree. They were accompanied by the sounds of celestial music and the scent of sweet perfumes wafting in the air.

Joan knew the two saints immediately of course; all young women knew Saint Catherine as the patron saint of needlework. The women conversed and then continued to meet regularly every week to discuss matters of theology that the deeply religious girl wanted answers about. But the time came when Catherine had to deliver her message from Saint Michael: “Orléans is under siege by the English and God wants you to become a warrior maid and save France.” Catherine had suggested to Michael that Joan be allowed to choose a less militaristic solution, but Michael had very set ideas and he claimed to be operating on direct orders from above. Saint Catherine herself commanded a loyal following among young religious girls and if she had had her way, she would have trained Joan in the ways of the mystic, not the warrior, but she had no choice. Initially Joan was doubtful, but over the next few years she gained in confidence for the task ahead, even as Catherine wondered if her heart was truly in it. Catherine taught her to cut her hair like a man and wear men’s clothes as she had done and she stressed to Joan the importance of remaining a virgin. This proved easy, for she doubted Joan liked men. Joan was only 17, so young and trusting. What followed was systematic rape in Catherine’s view – a betrayal by all who knew her.

When Joan finally was burned at the stake, Catherine saw that her heart remained full of blood and could not be burnt despite all the oils, sulfur and charcoal heaped upon it by her executioners. This was a sign that physically at least she was a virgin when she died. But in Catherine’s mind, Joan had lost her virginity to the men symbolically, which is to say that she felt Joan had been raped, psychologically and spiritually. War brutalizes us all, but its principal victims are women.

Catherine herself was born into a respectable upper class family in Alexandria and was lucky enough to receive a good education. When she refused to marry the Emperor on the grounds of her prior marriage to the infant Jesus, he put her on trial against 50 pagan philosophers. She engaged them in metaphor and she was proud to say that she vanquished them all. In a rage, the Emperor had all 50 of the philosophers burnt alive for, remarkably, they had become filled with the holy spirit and wanted to become Christians. He then had Catherine stripped and beaten with scorpions, thrown into prison, tortured by hunger, and finally chained to a spiked wheel which miraculously broke apart when they strapped her onto it (this is the origin of the fireworks known as the Catherine Wheel). The Emperor shrieked with frustration and had half the court beheaded before turning his attention once more to Catherine. “Off with her head!” he yelled and his goons rushed her. When they cut off her head she bled holy milk, its sticky whiteness splashing on their clothes and staining the floor. As you may know, such milk can flow only from virgin breasts. Angels then carried her body to Sinai where it exudes perfume to this very day.

Through the centuries, Catherine remained nostalgic for what Joan might have become. The way of the mystic is the way of feminine wisdom, strongly life-affirming, not destructive. Spiritually oriented women, Catherine argued, must create a private space for themselves as mystics, where the inner life of the self is more important than the outer world of military and political power, which will always be dominated by men. Women can express this inner life through their bodies, which contain the magical powers God bestowed upon them, especially through the virgin body which is the purest, most sacred shrine on God’s earth, for it is the source of life. Virginity inspires and intimidates men into behaving with proper respect for women. It is for this very reason that there have been many women saints and Christ himself was often described in feminine form.

Virginity can be an erotic and sensual experience in its own right, but it is not simply the sublimation of sexuality through denial. It is the essential first step upward toward a transcending spiritual union with Christ. At the second step, a certain level of pain and suffering through careful dieting may be required. Women are not forced to do this by male religious authorities. This is not masochism either. On the contrary, young anorexics and bulemics believe that their pain brings them closer to God, for self-inflicted suffering imitates Christ’s own pain and suffering on the Cross. Saint Catherine is therefore the patron saint of anorexics. Modern women have a tendency to suffer guilt and remorse when they diet, instead of regarding it as a healthy spiritual process. Such suffering is unnecessary if modern women can learn that through the pain of the Eucharist and fasting that they can attain that higher mystical state. Women must learn to renounce food while the men must renounce power.

Unfortunately, Joan of Arc enjoyed a good feast. She could have followed in the grand tradition of the great female mystic saints like Catherine of Siena before her and Theresa of Avila after her but she failed to restrain her appetites. Consequently Joan put her own sainthood in doubt for many centuries. But in the end she too qualified. The Church needs women warriors just much as it needs mystics.

SAINT MARGARET OF ANTIOCH

The other saint in the tree at Domrémy was Saint Margaret of Antioch. Like Catherine, she refused a forced marriage when she was 15 by claiming she was the virgin bride of Christ. She wasn’t technically a virgin by then, but that turned out to be neither here nor there.

Margaret’s father was the chief priest of the pagan cult that had married her off, and the cult’s unsavory reputation allowed the Governor to have her thrown in prison, where she was savagely beaten. Later, while sitting in her cell, she was attacked and swallowed by the Devil himself who had assumed the form of a huge dragon. Sexual implications aside, the important thing is that Margaret’s faith held and the dragon spat her out as indigestible. He then changed shape into a handsome young stud, thus obligating Margaret to go on the attack. She tackled him and threw him to the ground. “Proud demon, lie prostrate beneath a woman’s foot,” she yelled. It must have felt good. But the authorities felt threatened by this independent streak and they tortured and stripped Margaret and finally beheaded her. This happens sometimes when men are rejected by women. At any rate, the story about the dragon is the source of Margaret’s reputation as the patron saint of women in childbirth. Margaret wasn’t Joan of Arc’s favorite saint, but she liked the dragon story.

Margaret did not consider Joan a virgin when she was burnt her at the stake, but she was a virgin in the sense that she had never been with a man. After all that horse-riding and fighting, could it have been otherwise? Where Saint Michael and Saint Catherine were a little vague about the physical inspections, Saint Margaret knew it for the charade it was. After all, the King’s mother-in-law and the Duchess of Bedford could hardly have been expected to know what they were looking for. Of course they found the hymen; they too wanted to believe in the miracle of la Pucelle. There is reason to believe the same thing happened at her trial in 1431, with the result that Joan’s judges were forced to probe for other heresies. They found the idea of heavenly Voices quite natural but what they really wanted to know was whether her Voices were from God or from the Devil, and they hated the idea that a woman would wear men’s clothes or involve herself in politics. What bathroom should she use? The cross-dressing in particular opened up potential charges of heresy. Joan did not recognize their authority to try her on these charges and this drove them into a fury. She refused to fall into their snares and deflected anything that might incriminate her. The English lords lewdly suggested that they would rape her when they paid her visits, but she always managed to elude their grasp. In the end, after she promised not to wear men’s clothes again, the English guards took her own clothes from the cell and left her only men’s clothes. The end was now in sight.

Joan’s military and political successes had made her the talk of France, indeed Europe, rallying more troops to the French side. The poet and scholar Christina de Pisan was moved to write, just after the lifting of the siege of Orléans and before her own death: “What honor to the feminine sex... the kingdom, once lost, was recovered by a woman, a thing that men could not do.” Furthermore, once she was captured, Joan articulated an equally brilliant intellectual defense against her inquisitors, turning the questions around on some of the most influential religious figures of the time. Indeed there were many religious scholars in Rouen for her trial and throughout France who saw the trial for the sham it was.

Like Catherine, Margaret did not feel it was necessary that Joan die in order to liberate France. It never is, but somehow it always turns out that way when male saints are directing events. In Margaret’s view, women-hating was at the root of the Church’s thinking about sexuality and spirituality through the centuries. How else to account for the success of Eve, Delilah, Mary Magdalene, all women associated with sin and sex who were invoked in sermons throughout the Middle Ages. Most of the time, male clergy were able to ignore women, but there were undoubtedly times when they were forced to confront their temptations, which is why many clergy became sadistic, to Joan as much as to Margaret or Catherine. Female masochism and hysteria become understandable options for women who can see no other way out. The male clergy tried to soften this by increasing the number of women saints and by creating the cult of the Virgin Mary, essentially a cult of virginity and chastity for women. But, this meant that men had managed to split women in two: saints and sinners. Either way, women were identified with their bodies, with the demands of the flesh, which like all human forms could rot away. Similarly, men denied women political power on the grounds that since women were obsessed with their bodies, they were unsuited to the intellectualism required for it. Still, the Virgin Mary cult successfully attracted huge numbers of women into the Church and many religious women cleverly subverted this cult, turning it away from the physical into the metaphysical. Not all women intellectuals approved of those idealized images of the Virgin Mary, which for them came across only as the reflections of male icons and symbols.

Joan, you will recall, saw neither the Virgin Mary nor Mary Magdalene in the fields of Domrémy. Rather, she saw saints that empowered her – saints that threatened the established political and religious authorities. These stories took on additional force as local folklore added overlays, for example that Joan never menstruated, which her supporters saw as proof of her semi-divine nature, for that meant she was more like a man. Some added that she never sweated, never had bad breath, had no dandruff, and never excreted.

The blurring of those fixed identity lines in medieval times between men and women is intriguing. Women apparently were not good enough as women, let alone as men! The Church even proposed the curious idea that religious men could be better women than women, which is why Christ is often portrayed in feminine terms, to remind men that if they wish to enter heaven, they have to become weak and humble – like a woman. Some men even had the nerve to recommend that women should become more like men. For many ascetic religious women, they saw no choice but to punish themselves. If they did not get blamed for causing impotence in men, sex with the Devil, and what not, they were harder still on themselves. It would get worse. Later in the century the Inquisition would arrive in full force and witchcraft and heresy trials would accelerate. Muslims and Jews would be next.

VOLTAIRE

For Voltaire, Joan was not a virgin when she died. While he did not know exactly when she lost her virginity, he thought the smart money was on the debauchery that followed the King’s coronation in Reims. This helps to explain why she did not hear from her Voices again after that, until her trial.

Voltaire first raised these issues in his poem, La Pucelle (The Maid of Orléans), which he started writing around 1730. While living at Cirey, not far from Domrémy, he fleshed it out further. His Joan is a sexy tavern girl of 27 who pretends she’s 16, and the plot turns on how long she can avoid being raped by the English, and by her own knights for that matter. Many of them testified later that they had indeed tried to grab at her breasts and been slapped for their trouble. He has a fine old time skewering Joan’s image as Catholic virgin martyr, which is why he never had the poem published. It is true Voltaire added a little nakedness here and there and a little vulgarity to spice it up, but he liked Joan and he was much more critical of the hypocrites who served with her and condemned her to death -- the Church, the monarchy, old people – who rewrote history to suit themselves. “History is, after all, nothing but a parcel of tricks that we play upon the dead,” someone once wrote (a quote sometimes erroneously attributed to Voltaire).

Voltaire would get into trouble for this poem many years later during a three-year stay in Berlin at the court of King Frederick II (the Great). Voltaire decided that Frederick not only had ambitions to conquer French poetry but all of Europe as well. In their conversations, Frederick could not but be reminded that Joan was from Lorraine, one of France’s more “Germanic” provinces and at that time an independent duchy. Perhaps he sincerely believed that Joan could be enlisted as a mercenary for hire in the interests of Prussian nationalism. He saw that far from being the Peacemaker her adoring fans had always claimed her to be (on the theory that only through war can there be peace), he also saw that she had become an emblem of war. She embodied the idea that peace needs to be uprooted periodically through war in order to bring about change. Voltaire had to flee Berlin in 1753, not only because he had completely alienated Frederick by now with his continuous jibes at the homosexual atmosphere at Sanssouci Palace, but also because pirated copies of his poem about Joan were circulating and he was being blackmailed by erstwhile friends to whom he had lent a canto or two.

In the subsequent century, conservative French Catholic monarchists would argue that Joan was sent by God to restore the unity of France and the legitimacy of the Church and that if anyone was responsible for Joan’s death, it was the damned English. Popular folklore chipped in with more embroidery. One of those tales tells how Joan was the illegitimate daughter of Queen Isabelle of Bavaria (the Germans again) and Louis of Orléans! Smuggled out of Paris, she was raised in secrecy in Domrémy and it was her royal blood that gave her the power to persuade many noble knights to escort her to see the Dauphin. This pops up in a popular book charmingly titled Operation Shepherdess (published 1961). In another story Joan avoided being burnt at the stake by escaping from her English captors and living another 18 years in relative obscurity. Well, it is as good a theory as any.

But why was Joan of Arc so appealing to the Germans? In Friedrich von Schiller’s tragedy of 1801, Die Jungfrau von Orleans (The Maid of Orléans), she plays the French national heroine and ends up dying in battle instead of at the stake. This is of course more suitable to the interests of German Romanticism. Loyal French historians like Michelet went to the rescue and the French Catholic Church, on reading him, took up Joan’s cause from 1869 onwards to actively petition the Vatican for Joan to be made a saint. This viewpoint gained ground against the skeptics and republicans through the rest of the 19th century. From the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth, she came to symbolize right-wing jingoism, national and racial purity myths – in short, Fascism. There is something terribly sad and ironic about this, for if there is one metaphor that emerges out of the many in the context of virginity, it is betrayal. For Joan was betrayed all along the way, not least by the Dauphin and the French military commanders – in short, by adults who could not, or would not, appreciate that a teenager could succeed where they could not, and who preferred political intrigue over military action.

Joan would be exploited (raped) again in the Dreyfus Affair of the 1890s, a watershed in French political life that divided liberals and conservatives (more here). As nationalist sentiments intensified, the Fascist Right hijacked Joan as one of their own. The liberal French novelist and poet Anatole France tried to capture Joan back for rationalism in 1908 by arguing that her mysticism was just a form of hysteria and neurosis brought on by the religious excesses of the late Middle Ages. Good try but it hurt her case as much as it helped it, for the psychologists then got to work on her sexual identity problems, lesbian tendencies, and so on, to explain away why those knights never got anywhere with her. But she found unexpected support from gentle cynics like Mark Twain (1896) and George Bernard Shaw (1923), whom she seduced into writing glowing tributes – the true inheritors of Voltaire’s spirit. They opined that they wished they had known Joan better, in a manner of speaking, but you will recall that they had terrible love lives. Vita Sackville-West (1936) admired her for the way she lived life as a man, much as Sackville-West aspired to do.

By the time Joan became a saint in 1920, she was sponsoring at least three cults that were converging in the unifying image of French nationalism: the Catholic saint, the republican anti-saint, and the populist peasant girl heroine. It would be interesting to try to argue that France was symbolically unified in 1920 like never before or since. If Fernand Braudel’s argument that it wasn’t the French Revolution that unified France but the railway train, then time-wise this would seem like a good fit. However, as political dissension grew again through the 1920s and 1930s, so too did Joan’s image split apart again into the various cults. In World War II she was again claimed by the Germans sponsoring Vichy France, who appealed to traditional rural Catholic values, portraying her as a symbol of national suffering with the potential for redemption in case they lost. (In Spain they were doing the same with Teresa of Avila.) The Communists staged another rescue mission, proclaiming Joan a rebel and a freedom fighter against the Germans. But the most emotionally satisfying moment in the whole sorry saga occurred on Liberation Day, May 1945, when Charles de Gaulle and his soldiers marched to her statue in Paris and all the metaphors converged as one. De Gaulle was exceedingly clever when he adopted the Cross of Lorraine as the symbol of Free France. Whatever Joan’s evolving reputation, Lorraine was now certifiably French and not German and de Gaulle understood better than anyone the mystique of her image in rallying France. Since World War II, she has been claimed again by the Catholics, monarchists and the Fascist Right, with Le Pen and the National Front arguing that if Joan expelled the English, she could help the French get rid of the Arabs. However, it is those arresting images of De Gaulle on Liberation Day that redeems Joan for all time.

Joan of Arc was the superhero of her age and as with all superheroes, fights have raged over her and perverse cults have sprouted like mushrooms. This is not surprising, given that her story is a fairy tale with a grotesque ending. Traditional France has kept it alive partly because she was one of them, partly because her devoutness remains impressive in a secular age, and partly because constantly improving on the original is a traditional French pastime.